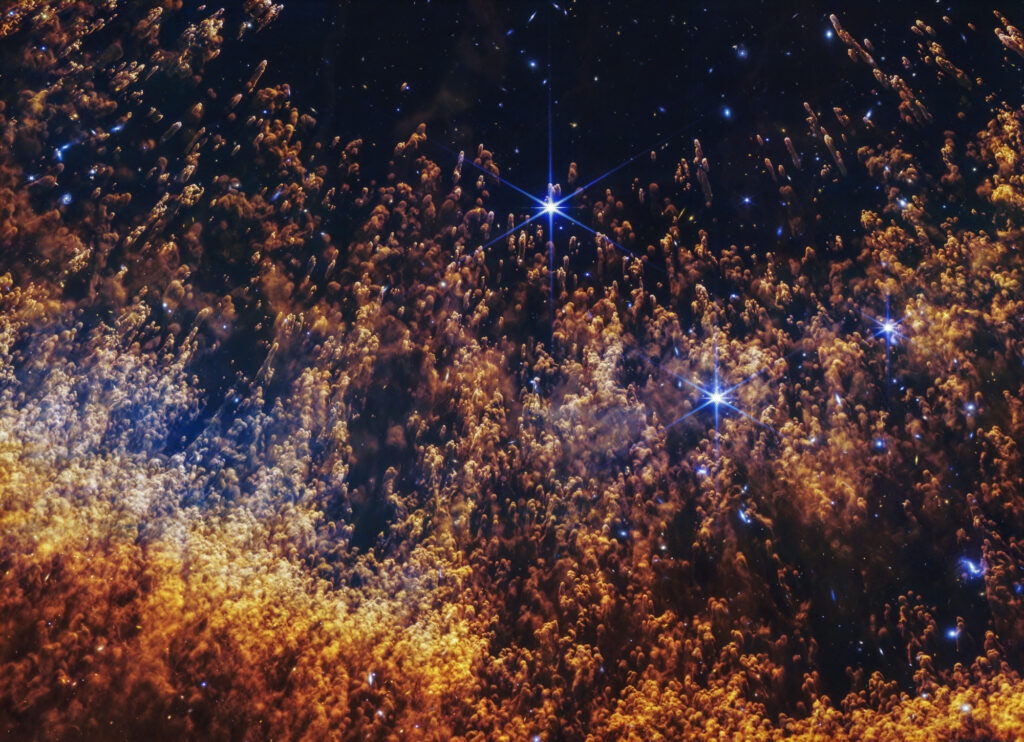

NASA / ESA / CSA / STScI / A. Pagan (STScI)

The James Webb Space Telescope team has released a stunning new close-up of the Helix Nebula, 650 light-years away in the constellation Aquarius. The image homes in on the nebula’s expanding shell, where thousands of comet-like knots have formed.

The appearance of the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293) is surprisingly similar to the supernova remnant Pa 30. While Pa 30, discovered and named in 2013 by amateur astronomer Dana Patchick, is more than 10 times farther away than the Helix, telescopes have revealed firework-like tendrils in the remnant that appear similar to the features in the Helix — and a new study suggests they have a similar explanation.

Swirls in Space

When various gases encounter each other in the cosmos, there are a few effects that may govern their introduction. These effects start small but quickly grow. Rayleigh–Taylor instabilities create swirls where fluids of different densities meet, like when you pour milk into your coffee. On the other hand, Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities occur when there’s a velocity difference across the interface between two fluids, like when winds make waves on the surface of the ocean. (In that example, wind is acting as a fluid.) In fact, both instabilities (and other ones) could even occur at the same time.

So what’s happening in the Helix Nebula and in Pa 30? We’re watching Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities at play in both cases. But the reasons aren’t quite the same.

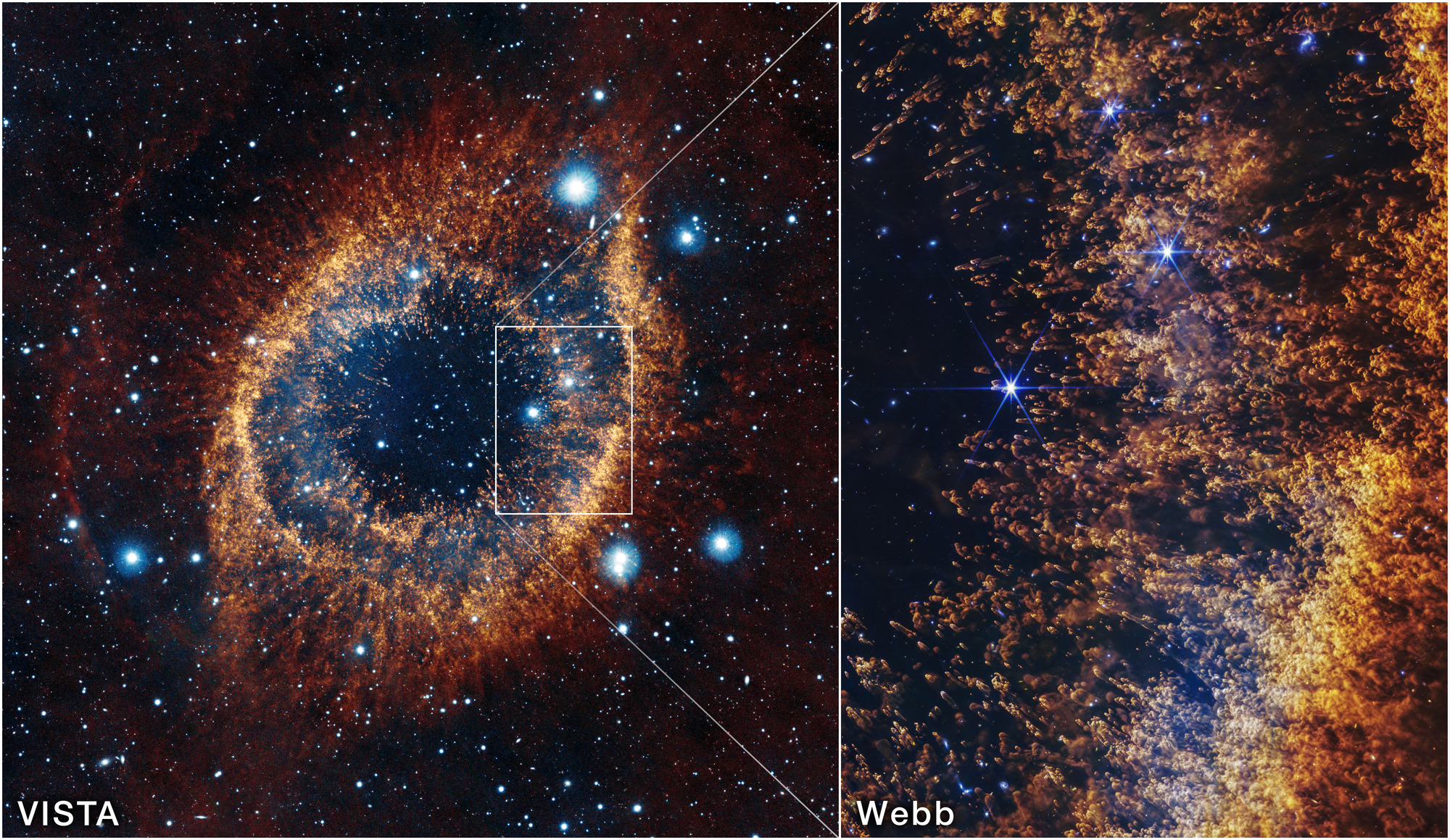

NASA / ESA / CSA / STScI / A. Pagan (STScI)

The Helix is a planetary nebula, marking the death of a low-mass star like the Sun. Near the end of its life, that star puffed off its outermost layers before collapsing in on itself to make a white dwarf. Now that incandescent ember has set the nebula’s gases alight.

That intense radiation carries weight, pushing thin gas away and leaving denser clumps behind, says Macarena Garcia Marin (Space Telescope Science Institute), who led the team making the Webb observations. “At the same time,” she adds, “the Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities contribute to the creation of these shapes.” A tenuous wind of charged particles coming from the white dwarf helps sculpt the clumps into comet-like pillars.

The Hubble Space Telescope had previously imaged Helix, finding thousands of these “cometary knots.” What Webb is now adding to the equation is a clearer view of the chemistry within the shell. Its near-infrared observations reveal the transition from hot gas nearer the white dwarf out to where dust grains form farther out. “These new Helix data are very useful to further explain mechanisms on how these structures form,” Garcia Marin says.

X-ray: (Chandra) NASA / CXC / U. Manitoba / C. Treyturik, (XMM-Newton) ESA / C. Treyturik; Optical: (Pan-STARRS) NOIRLab / MDM / Dartmouth / R. Fesen; Infrared: (WISE) NASA / JPL / Caltech; Image Processing: Univ. of Manitoba / Gilles Ferrand and Jayanne English

In recent simulations published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, Eric Coughlin (Syracuse University) and colleagues find that similar physics are probably happening in Pa 30 — even though this dying star is a different kind of beast.

While Helix marks the formation of a white dwarf, Pa 30 marks another white dwarf’s near-destruction — a rare event. Pa 30 is a remnant of a Type Iax supernova, in which a runaway nuclear reaction occurs on the surface of a white dwarf as it hauls in material from a companion star. But somehow, the blast fails to destroy the white dwarf — it leaves a “zombie star” behind.

Amateur astronomer Dana Patchick discovered the nebula in archived images from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, provisionally naming it Pa 30 as part of his catalog of planetary nebulae. The remnant is some 8,000 light-years away in Cassiopeia. But further investigation found that the nebula is actually a supernova, probably matching the one observed from Earth 845 years ago in AD 1181.

Pa 30’s identification took some time because of its unique look. Unlike other supernova remnants, its gases are moving outward in thin, firework-like tendrils. Now, Coughlin’s team has conducted computer simulations to understand the blast’s odd appearance. And once again, it comes down to the Rayleigh-Taylor instability.

Only this time, the wind from the leftover white dwarf at the center of Pa 30 is dense, not tenuous. Those particles are running into comparatively sparse gases around the star. It’s the opposite density setup from the Helix, but with the same result. The difference between the winds and the material they’re running into sculpts the gaseous plumes.

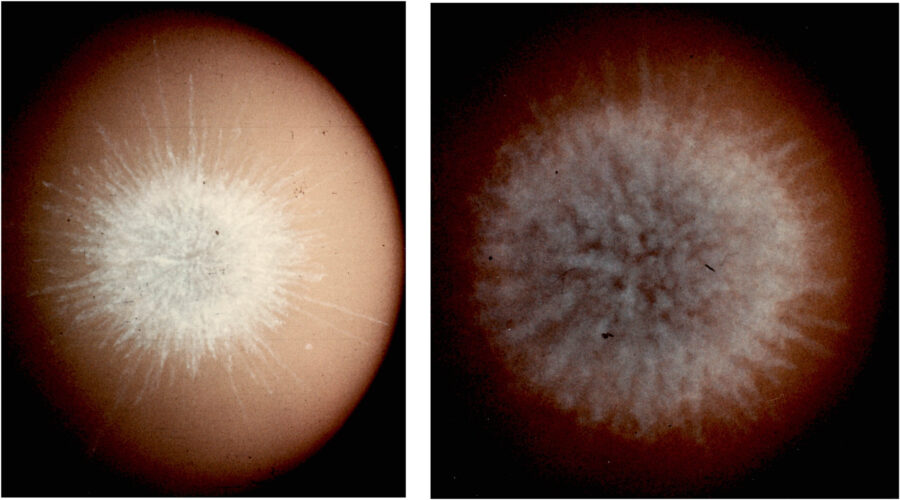

Coughlin et al. / Astrophysical Journal 2025

That’s different from most supernovae, which evoke cauliflowers more so than fireworks. Coughlin’s team finds a potential explanation in an earthly reference, with a look to images of the “Kingfish” high-altitude nuclear test in 1962. The Kingfish blast first formed filaments, strikingly similar to Pa 30, before morphing into to bunchier shapes. Perhaps, the team suggests, exploding white dwarfs all go through a brief fireworks stage, and Pa 30 just stuck around in that stage a little longer.

“In a matter of speaking, the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability would ‘try’ to destroy the tendrils, but it can’t,” says Garcia Marin. “The density contrast between the wind and the surrounding material is too large for effective mixing.”

There’s plenty else happening in both the Helix Nebula and Pa 30, such as the ionizing effects of the central white dwarfs. Still, it’s amazing to think that the same physics that goes on in your morning cup of coffee shapes the appearance of blasts from dying stars.