The interstellar comet! Can you see it in your scope? Starting in mid-November, as Comet 3I/ATLAS emerges from behind the Sun, indeed you can. . . if you have a large amateur telescope with which you can detect an 11th- or 12th-magnitude faint fuzzy rather low in the east just before the beginning of dawn. That probably means at least an 8-inch scope, maybe larger.

Conditions will start very tough for mid-northern observers, then will improve. Writes Bob King: “On November 9th, the comet achieves an altitude of 10° just before the start of dawn for observers at 40° north latitude. The Moon will be in waning gibbous phase on that date and could pose a problem for visual observers. By the 16th, the comet’s altitude doubles to 20° with the Moon a thin crescent located 4° to its south.” See his All Eyes on Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS. The finder chart there starts on the morning of November 17th, as the comet passes Gamma Virginis. Get ready.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 31

■ Halloween evening this year finds the waxing gibbous Moon shining in the south with yellowish Saturn glowering to its left, by almost two fists at arm’s length. Farther below the Moon twinkles lonely Fomalhaut.

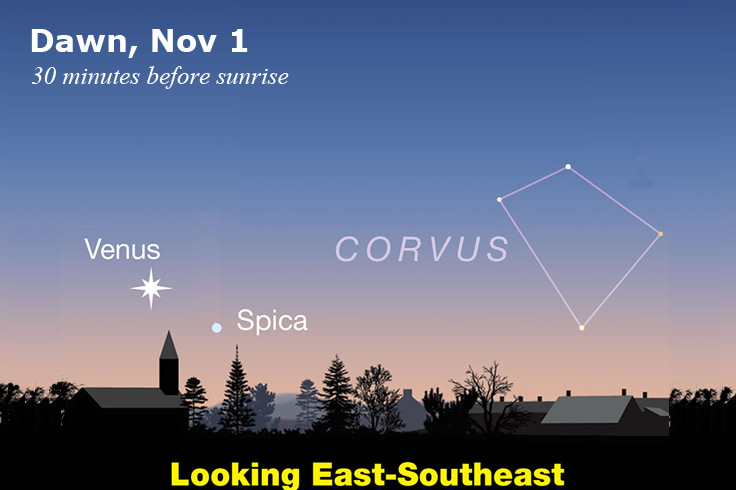

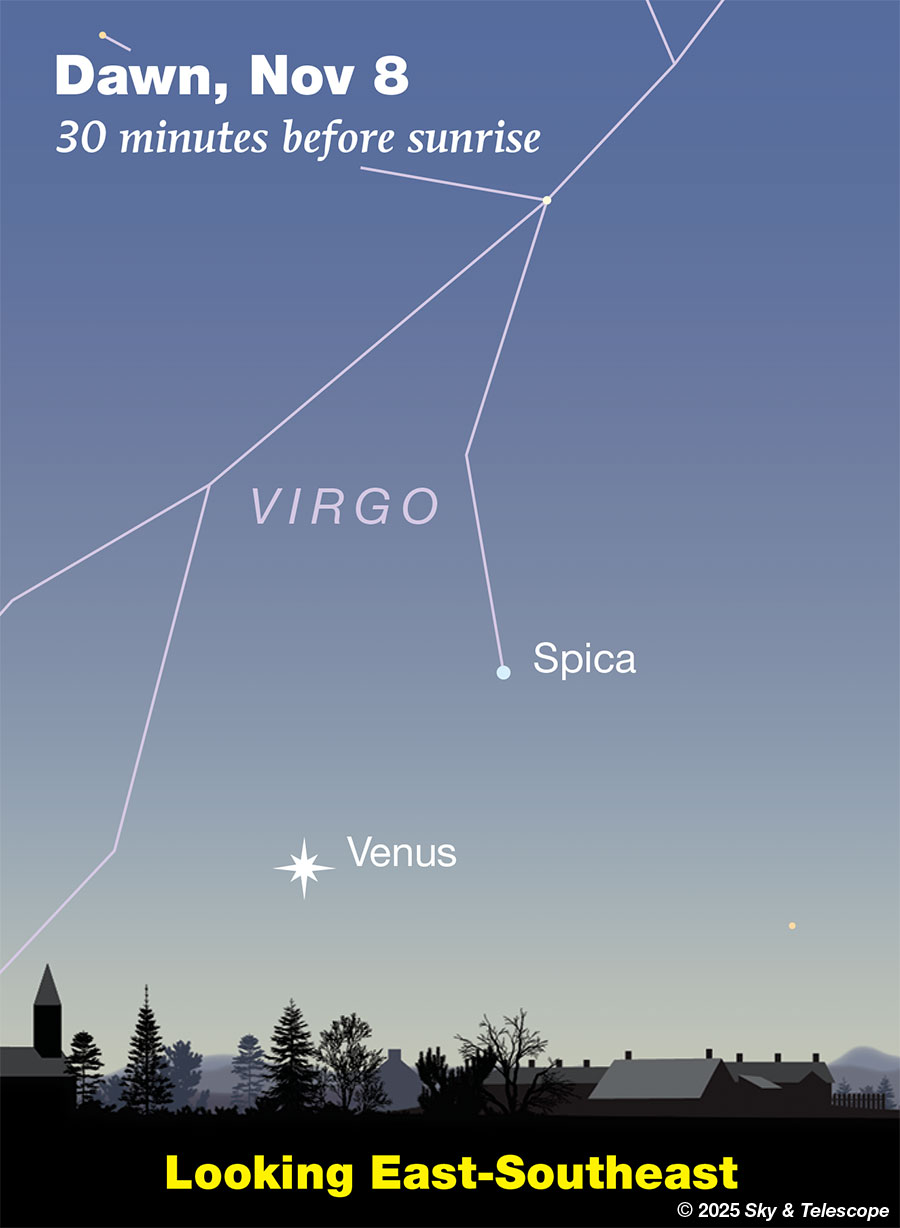

■ A dawn challenge: Early in Saturday’s dawn, can you pick out Spica to the lower right of Venus as shown below? They’re 3.6° apart. The star, magnitude +1.0, is only 1% as bright as Venus, magnitude –3.9.

On Sunday morning they’ll be a trace closer at conjunction, 3.5° apart. After that they’ll start to widen.

Spica is barely emerging from solar conjunction. You’ve almost certainly never seen it before at this time of year!

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 1

■ Daylight-saving time ends at 2 a.m. tonight for most of North America. Clocks fall back an hour.

■ The waxing gibbous Moon shines near Saturn tonight for North America. Watch them draw closer together through the night, from dusk until they set in the west around 3 or 4 a.m. Sunday morning standard time.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 2

■ Around 10 p.m., depending on where you are, zero-magnitude Capella rises exactly as high in the northeast as zero-magnitude Vega has sunk in the west-northwest. How accurately can you time this event?

The answer, with judicious use of the stars’ celestial coordinates, a nautical almanac, and some seriously not-simple paperwork, can give your latitude and longitude. This is the kind of thing sailors once did using sextants. Or, try a modern version backwards! Using a planetarium program set for your known location, run the time back and forth until Capella and Vega stand at the same altitude. Read off the time. How well or poorly does your naked-eye estimate match this? Can you get better with practice?

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 3

■ When night arrives, the Great Square of Pegasus is still balanced on its corner high in the southeast. Find it tonight above the Moon and Saturn (which is right of the Moon). But within two hours the Square turns around to lie level like a box high in the south, now with the Moon to its lower right.

A sky landmark to remember: The west (right-hand) side of the Great Square points far down almost to 1st-magnitude Fomalhaut, about four fists below. The east side of the Square points down toward Beta Ceti (not as directly), three fists below.

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 4

■ Algol in Perseus, posing in the northeast, dips to its minimum brightness, magnitude 3.4 instead of its usual 2.1, for about two hours centered on 10:12 p.m. EST. Algol takes several additional hours to fade and to rebrighten. Comparison-star chart.

■ The Summer Triangle Effect. Here it is November, but Deneb still shines near the zenith as the stars come out. And brighter Vega is still not far from the zenith, toward the west. The third star of the “Summer” Triangle, Altair, remains high in the south-southwest. They seem to have more or less stayed there for a couple of months! Why have they stalled out?

What you’re seeing is the result of sunset and darkness arriving earlier and earlier during autumn. Which means if you go out and starwatch soon after dark, you’re doing it earlier and earlier. That counteracts the seasonal westward turning of the constellations.

Of course this “Summer Triangle effect” applies to the entire celestial sphere, not just the Summer Triangle. But the apparent stalling of that bright landmark inspired Sky & Telescope to give it that name many years ago, and it stuck.

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 5

■ Full Moon (exactly full at 8:19 a.m. on this date EST). This is a supermoon, since the Moon is near the perigee of its orbit. This evening, and yesterday evening too, it appears 7% larger than average — which is barely enough to see for sure even if you’re a frequent Moon watcher.

THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 6

■ The bright Moon, just a day and a half past full, rises in twilight. Once night comes on, look for the Pleiades about 7° (four finger widths at arm’s length) to the Moon’s upper right. Cover the Moon with your hand to hide its glare.

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7

■ We’re now at the time of year when Orion is nicely up in the east-southeast as early as 10 p.m. This evening you’ll find it lower right of the Moon.

And, tonight the Moon shines nearly on the line from bright Capella high overhead to Betelgeuse, Orion’s orange shoulder. Will the Moon cross this line tonight for your location? Hold up a yardstick between the two stars, or a taut string between your hands, to judge a straight line more accurately.

Also: Look close to the Moon for Beta Tauri (El Nath), which at magnitude 1.6 just misses being classified as a 1st-magnitude star. Cover the glary Moon with your fingertip. The Moon’s bright limb will occult Beta Tauri for central South America and west-central Africa.

■ Algol again dips to its minimum brightness, magnitude 3.4 instead of its usual 2.1, for about two hours centered earlier this time: 7:01 p.m. EST. Every Algol dip happens three hours earlier than the previous one three days before.

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 8

■ Draw a line from Altair, the brightest star high in the southwest after dark, to the right to Vega, similarly high in the west and even brighter. Continue the line onward by half as far, and you hit the Lozenge: the pointy-nosed head of Draco, the Dragon. Its brightest star is orange Eltanin, the tip of the Dragon’s nose, always pointing toward Vega.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 9

■ The waning gibbous Moon rises around 9 p.m. local standard time. As always, the exact time depends on your location. Jupiter follows it up a half hour later, about 4° to the Moon’s lower right. Pollux and Castor are to the Moon’s upper left.

This foursome forms a ragged diagonal line. Watch the line change shape hour by hour as the Moon moves eastward along its orbit. Later the line will become a smoothly curving arc. The time when this happens this will also depend on your location.

■ Happy 91st birthday, Carl Sagan (November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996). If only.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury is just about a goner if it isn’t already. It’s not only very low in bright twilight, it fades now too, losing nearly half its brightness over the course of the week: from magnitude –0.2 on Friday October 31st to mag +0.4 on Friday November 7th. It’s located barely above the west-southwest horizon 30 minutes after sunset.

Venus (magnitude –3.9) rises in the east during early dawn, a bit more than an hour before sunrise. It’s getting lower every week.

Mars (magnitude +1.5) is lost in the sunset, fainter than even Mercury a few degrees to its left.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.3, in eastern Gemini) rises in the east-northeast around 10 or 11 p.m. daylight-saving time; 9 or 10 p.m. standard time. It dominates the east, then the southeast, as late night advances. Castor and Pollux shine upper left of it, then above it by the beginning of dawn. By then the three stand very high in the south — with Procyon below them and Orion standing upright farther to their lower right.

Saturn (magnitude +0.9, at the Aquarius-Pisces border) is the brightest dot high in the southeast at nightfall. Find the Great Square of Pegasus upper left of it early in the evening and straight above it by the time Saturn transits the meridian (due south) around 10 p.m. daylight-saving time; 9 p.m. standard time.

Saturn’s rings are now very nearly edge-on, looking in a telescope like a long, faint needle piercing a bright cheeseball. Their shadow on the planet is a stark black line along its equator. This aspect of Saturn is a sight to remember and one we won’t see again, after this season, for another 15 years. How old will you be then?

Earth will pass through the plane of Saturn’s rings on November 23rd. Around that date they’ll be completely invisible, leaving Saturn as a bare oblate globe divided by a thin black line.1

Uranus (magnitude 5.6, in Taurus 4° south of the Pleiades) is well up by 8 p.m. standard time; 9 p.m. daylight time. At high power in a telescope it’s a tiny but definitely non-stellar dot, 3.8 arcseconds wide.

Neptune is a telescopic “star” of magnitude 7.8, a dim pinhead just 2.3 arcseconds wide 4° from Saturn.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Standard Time (EST) is Universal Time minus 5 hours. Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is UT minus 4 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

For the attitude every amateur astronomer needs, read Jennifer Willis’s Modest Expectations Give Rise to Delight.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas, in either the original or Jumbo Edition. Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, and 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as many more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used.

The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum Deep-Sky Atlas (with 201,000+ stars to magnitude 9.5 and 14,000 deep-sky objects selected to be detectable by eye in very large amateur telescopes), and Uranometria 2000.0 (332,000 stars to mag 9.75, and 10,300 deep-sky objects).

And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet (which many observers find more versatile) as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. It was my bedside reading for years. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the new Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners, I don’t think. Unless you prefer spending your time getting technology to work rather than learning how to explore through the sky yourself. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope for visual use, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Do learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

— John Adams, 1770

1. That was, by a total coincidence, how I saw Saturn for the first time ever through a telescope. It was October 27, 1966. I was 15 years old and looking through the historic 15-inch refractor atop Harvard College Observatory, during one of its legendary monthly open-night talks and telescope viewings for the public. My Dad brought me.

That was two Saturn orbits ago, and four ring-plane-crossing seasons ago. Actuarial tables say I have about a 50-50 chance of living to see the next one. . . which would certainly be my last.