Comets Lemmon and SWAN are still in binocular range, but they have probably passed their peak brightnesses. Both are nicely placed in the evening sky right after the end of twilight (for mid-northern latitudes).

SWAN this week moves from southern Aquila into western Aquarius: nicely high in the south after nightfall, but likely to be only 7th magnitude.

Lemmon this week will probably still be 5th or 6th magnitude this week as it across Serpens Caput, which is lower in the west at the end of twilight.

See Bob King’s Two Bright Comets Converge on Northern Hemisphere Skies with finder charts for SWAN, and his Sweet Prospects for Comet Lemmon with a current chart for Lemmon.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 24

■ A twilight challenge: About 30 or 40 minutes after sunset, find the thin crescent Moon very low due southwest. Use binoculars or a telescope at its lowest power to look for orange Antares twinkling near it. For North America, Antares will be a degree or two (about two to four Moon diameters) above or upper right of the Moon.

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 25

■ The Ghost of Summer Suns. Halloween is approaching, and this means that Arcturus, the star sparkling low in the west-northwest in twilight, is taking on its role as “the Ghost of Summer Suns.” For several evenings centered on October 25th every year, Arcturus occupies a special place above your local landscape. It closely marks the spot where the Sun stood at the same time, by the clock, during hot June and July — in broad daylight, of course!

So, as Halloween approaches every year, you can see Arcturus as the chilly, wan ghost of the departed warm summer Sun.

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 26

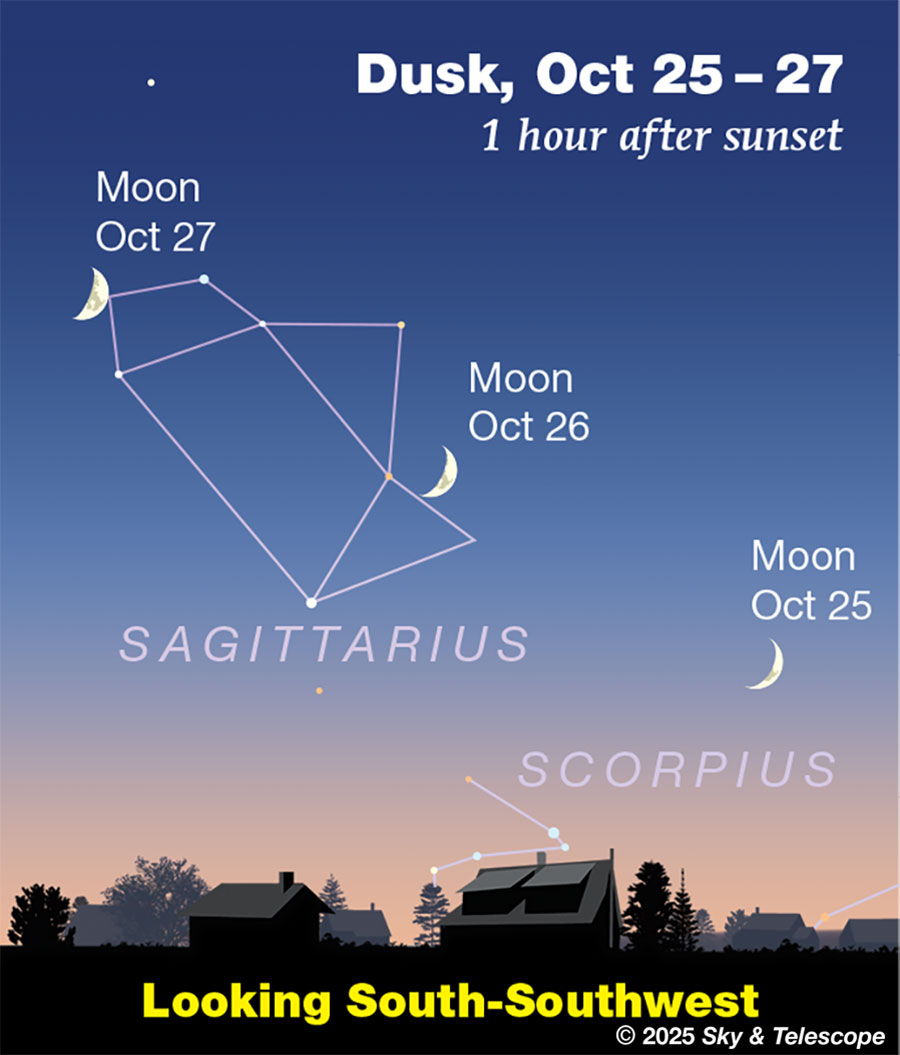

■ The waxing crescent Moon hangs low in the south-southwest as the last of twilight fades away. This evening the Moon floats just atop the spout of the Teapot for North American skywatchers, as shown below. Binoculars will help with the 2nd- and 3rd-magnitude stars. The whole Teapot is 14° wide, about two or three times the width of an ordinary binocular’s field of view.

MONDAY, OCTOBER 27

■ Now the waxing Moon hangs by the Teapot’s handle, which is both brighter and higher than the spout.

■ The dark limb of the Moon will occult the handle’s star Tau Sagittarii, magnitude 3.3, for much of the eastern U.S. and the Canadian Maritimes early this evening. Map and timetables. For instance, using the first timetable: From New York City the Moon’s dark limb will blink out the star at 23:36 UT, which is 7:36 p.m. EDT, when the Moon will be 16° above the south-southwest horizon.

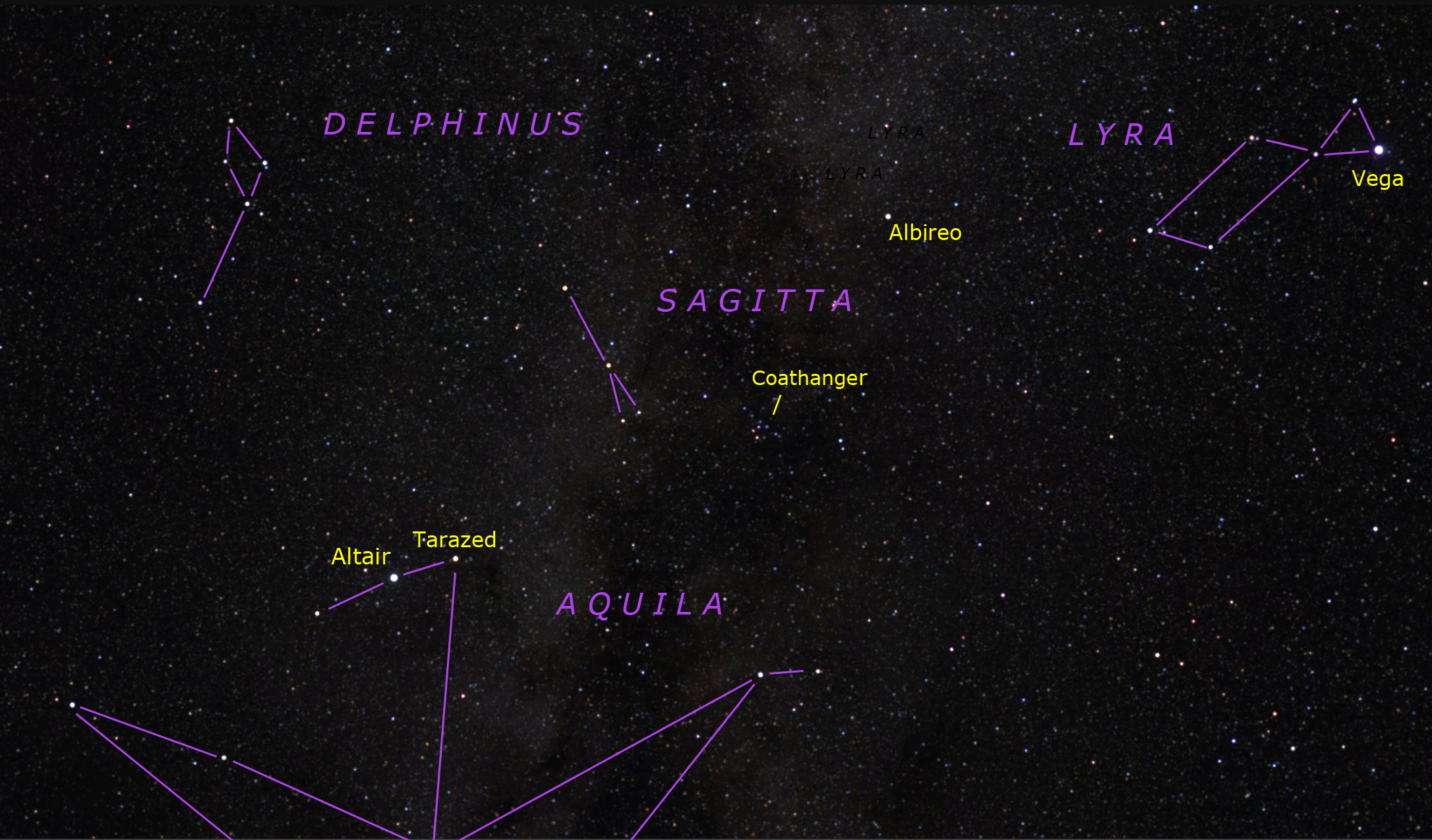

■ Spot bright Altair high in the southwest soon after dark. Brighter Vega is far to its right or upper right.

Above Altair lurk two distinctive little constellations: Delphinus the Dolphin, hardly more than a fist at arm’s length to Altair’s upper left, and smaller, fainter Sagitta the Arrow, slightly less far to Altair’s upper right. As shown below. Is your sky too bright for them? Bring binoculars!

Binoculars can fetch up the little Coathanger asterism off Sagitta’s tail. The Coathanger is upside down.

TUESDAY, OCTOBER 28

■ The Summer Triangle Effect. Here it is the end of October, but Deneb still shines right near the zenith as the stars come out. And brighter Vega is still not far from the zenith, toward the west. The third star of the “Summer” Triangle, Altair, remains very high in the south-southwest. They seem to have stayed there for a couple of months! Why have they stalled out?

What you’re seeing is the result of sunset and darkness arriving earlier and earlier during autumn. Which means if you go out and starwatch soon after dark, you’re doing it earlier and earlier by the clock. That counteracts the seasonal westward turning of the constellations.

Of course this “Summer Triangle effect” applies to the entire celestial sphere, not just the Summer Triangle. But the apparent stalling of that bright landmark inspired Sky & Telescope to give the effect that name many years ago, and it stuck.

Of course, as always in celestial mechanics, a deficit somewhere gets made up elsewhere. The opposite effect makes the seasonal advance of the constellations seem to speed up in early spring. The spring-sky landmarks of Virgo and Corvus seem to dash away westward from week to week almost before you know it, due to darkness falling later and later. Let’s call this the “Corvus effect.”

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 29

■ First-quarter Moon (exact at 12:21 p.m. EDT). The Moon shines in the center of the dim, boat-shaped constellation pattern of Capricornus. In a telescope this evening for North America, the Moon’s sunrise terminator nearly bisects flat-floored Plato at the northern edge of Mare Imbrium, and smaller, central-peaked Eratosthenes on Imbrium’s southern edge just off the end of the Apennine Mountains.

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 30

■ Look for bright Capella sparkling low in the northeast these evenings. Look for the Pleiades cluster about three fists at arm’s length to Capella’s right. These harbingers of the cold months rise higher as evening grows late. And watch for Aldebaran to come up below the Pleiades.

Upper right of Capella, and upper left of the Pleiades, the stars of Perseus lie astride the winter Milky Way.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 31

■ Halloween evening this year finds the waxing gibbous Moon shining in the south with yellowish Saturn glowering to its left (by almost two fists at arm’s length). Farther below the Moon twinkles lonely Fomalhaut.

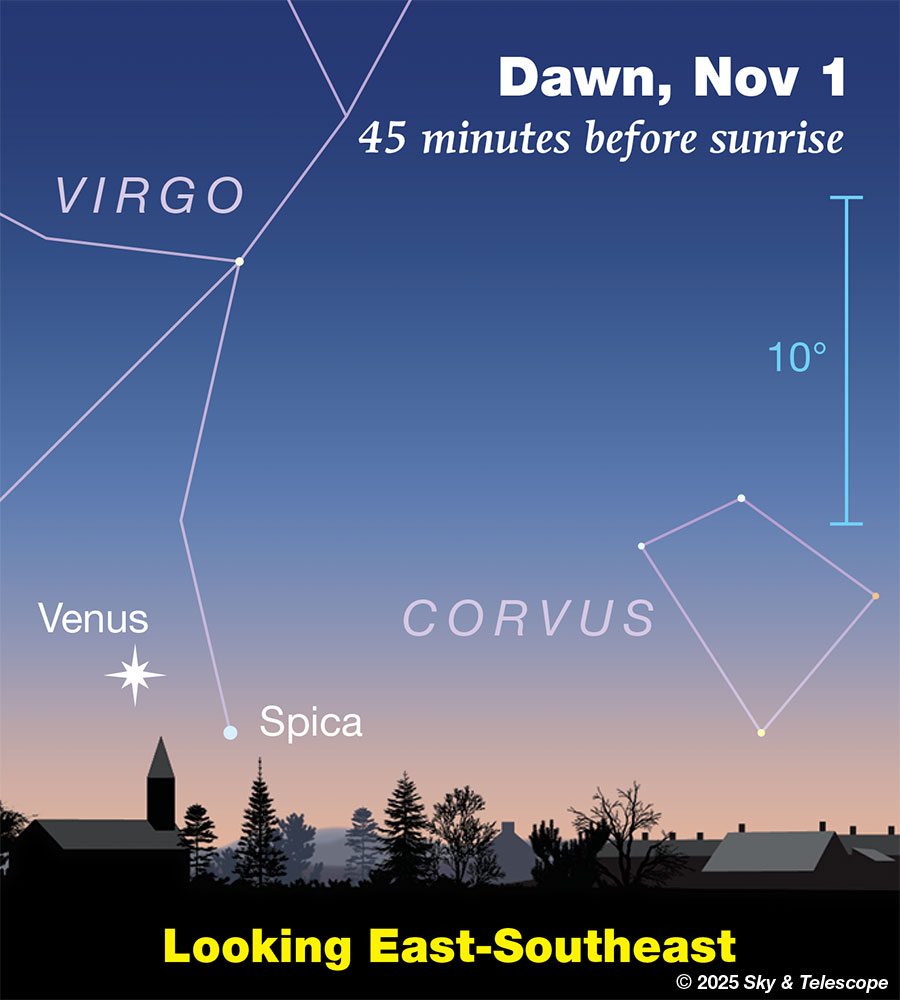

■ A dawn challenge: Early in Saturday’s dawn, can you pick out Spica to the right or lower right of Venus as shown below? They’re 3.6° apart. The star, magnitude +1.0, is only 1% as bright as Venus, magnitude –3.9.

On Sunday morning they’ll be a trace closer at conjunction: 3.5° apart.

SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 1

■ Daylight-saving time ends at 2 a.m. tonight for most of North America. Clocks fall back an hour.

■ The waxing gibbous Moon shines near Saturn tonight for North America. Watch them draw closer together through the night, from dusk until they set in the west around 3 or 4 a.m. Sunday morning standard time.

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 2

■ Around 10 p.m., depending on where you are, zero-magnitude Capella rises exactly as high in the northeast as zero-magnitude Vega has sunk in the west-northwest. How accurately can you time this event? Sextant not required. . . but it would help.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury (magnitude –0.2) remains very low in the bright afterglow of sunset this week despite being at greatest elongation. This apparition of Mercury is about as poor as they get. Starting about 20 minutes after sunset, try to spot it a little above the west-southwest horizon. Bring binoculars. Good luck.

Venus (magnitude –3.9) rises due east around the beginning of dawn. It seems to fade in the brightening dawn as it climbs upward, but that’s an illusion. Venus remains the same. Its appearance, when increasingly swamped by the brightening sky, is what changes. It’s another reminder that external reality, which exists independent of us humans, and our internal experience of this reality, as modeled within our neural-network brains, are two fundamentally different things — in fact, entirely different orders of being. So often we confuse the two, to our bafflement and misfortune.

Mars (magnitude +1.5) is lost in the afterglow of sunset a few degrees to the right of Mercury. Mars is only one fifth as bright as Mercury.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.3, in eastern Gemini) rises around 11 p.m. local daylight-saving time. It dominates the east, then the southeast, as the late night advances. Castor and Pollux shine upper left of it.

By the beginning of dawn the three stand very high in the south — with Procyon below them and Orion standing upright farther to their lower right.

Saturn (magnitude +0.9) is the brightest dot high in the southeast at nightfall. The Great Square of Pegasus poses upper left of it early in the evening and straight above it by the time Saturn transits the meridian (due south) around 10 p.m. In a telescope Saturn’s rings remain very nearly edge-on.

Uranus (magnitude 5.6, in Taurus 4° south of the Pleiades) is well up by 9 p.m. At high power in a telescope it’s a tiny but definitely non-stellar dot, 3.8 arcseconds wide.

Neptune is a telescopic “star” of magnitude 7.8, a dim pinhead just 2.4 arcseconds wide 4° from Saturn. Use the finder chart for Neptune with respect to Saturn in the September Sky & Telescope, page 49. With a pencil, put a dot on the path of each of the two planets for your date.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time minus 4 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

For the attitude every amateur astronomer needs, read Jennifer Willis’s Modest Expectations Give Rise to Delight.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas, in either the original or Jumbo Edition. Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, and 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as many more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used.

The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum Deep-Sky Atlas (with 201,000+ stars to magnitude 9.5 and 14,000 deep-sky objects selected to be detectable by eye in very large amateur telescopes), and Uranometria 2000.0 (332,000 stars to mag 9.75, and 10,300 deep-sky objects).

And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet (which many observers find more versatile) as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. It was my bedside reading for years. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the new Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Do learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

— John Adams, 1770