FRIDAY, MAY 16

■ In the sky tonight, Vega shines as the brightest star in the east-northeast. Look 15° (about a fist and a half at arm’s length) upper left of Vega for Eltanin, the 2nd-magnitude nose of Draco the Dragon. Closer above and upper left of Eltanin are the three fainter stars that form the rest of Draco’s stick-figure head, also called the Lozenge. Draco always points his nose to Vega, no matter how he’s oriented. Dragons do have a thing for jewels.

The faintest star of Draco’s head, opposite Eltanin, is Nu Draconis. It’s a fine, equal-brightness double star for binoculars (separation 61 arcseconds, both magnitude 4.9). The pair is 99 light-years away. Both are hot, chemically peculiar type-Am stars somewhat larger, hotter, and more massive than the Sun.

■ Look low to the east in early dawn Saturday morning the 17th to catch Venus shining brightly in its Morning Star role. To its upper right by about a fist at arm’s length look for Saturn, only 1/230 as bright. Binoculars may still give you a chance if dawn has already brightened too much. A big object will meet these planets several days from now.

How different Venus and Saturn look in a telescope! Venus is a dazzling thick crescent about 40% sunlit. Saturn is a vastly dimmer little ball with only 1/250 of Venus’s surface brightness. That’s mostly because Saturn is 13 times farther from the illuminating Sun than Venus is, and partly because Venus has an albedo of 65% compared to Saturn’s 47%. (Albedo is how much of the incoming light an object reflects.)

Both planets will be blurred and shimmery in a telescope in the low-altitude seeing. So you may see nothing of Saturn’s rings, which are nearly edge-on to us this year. Look for traces of a toothpick stuck diagonally (celestial east-west) through Saturn’s globe.

SATURDAY, MAY 17

■ As Vega climbs up the east-northeast these evenings, its little constellation Lyra, the Lyre, becomes easier to recognize. Lyra’s main pattern hangs down from Vega with its bottom canted to the right. Look for a little equilateral triangle with Vega as its top corner, and a longer parallelogram attached to the triangle’s bottom corner.

SUNDAY, MAY 18

■ This is the time of year when Leo the Lion starts walking downward toward the west, on his way to departing into the sunset in early summer. Right after dark, spot the brightest star fairly high in the west-southwest. That’s Regulus, his forefoot.

Regulus is also the bottom of the Sickle of Leo: a backward question mark about a fist and a half tall. It outlines the lion’s forefoot, chest, and mane.

MONDAY, MAY 19

■ The brightest asteroid, 4 Vesta, is nicely placed in a moonless dark sky in late evening. It’s about two weeks past opposition and still about magnitude 6.0. It’s located 24° below Arcturus, near the Virgo-Libra border, and about 9° and 10° above Beta and Alpha Librae, respectively. You’ll need the finder chart with Bob King’s article Asteroid Vesta Now an Easy Catch in Binoculars. (The dates on the chart are in Universal Time. Subtract one day from them to get evening dates for the Americas.)

If you have a really dark sky, can you detect Vesta with the unaided eye? It’s pretty much the only naked-eye dwarf planet, and only when near opposition.

TUESDAY, MAY 20

■ The last-quarter Moon (it’s exactly last-quarter at 7:59 a.m. EDT Wednesday morning) rises around 2 or 3 a.m. tonight. Upper left of it, by about two fists at arm’s length, the Great Square of Pegasus balances on one corner. The Square’s top right edge points down at the Moon.

Just before Wednesday’s dawn begins to make itself known, spot Saturn about a fist and a half to the Moon’s lower left. Continue farther lower left for almost the same distance, and that’s where Venus rises as dawn begins.

WEDNESDAY, MAY 21

■ With summer still a month away (astronomically speaking), the last star of the Summer Triangle doesn’t rise above the eastern horizon until about 10 or 11 p.m. That’s Altair, the Triangle’s lower right corner. Watch for Altair to clear the horizon three or four fists at arm’s length to Vega’s lower right.

The third star of the Triangle is Deneb, less far to Vega’s lower left.

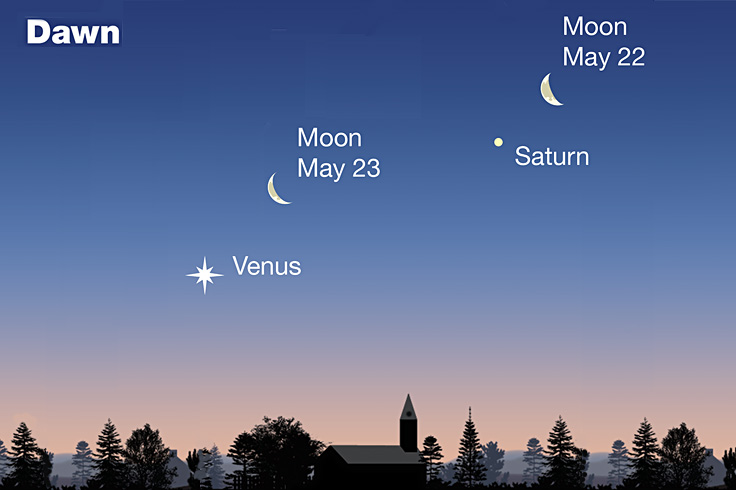

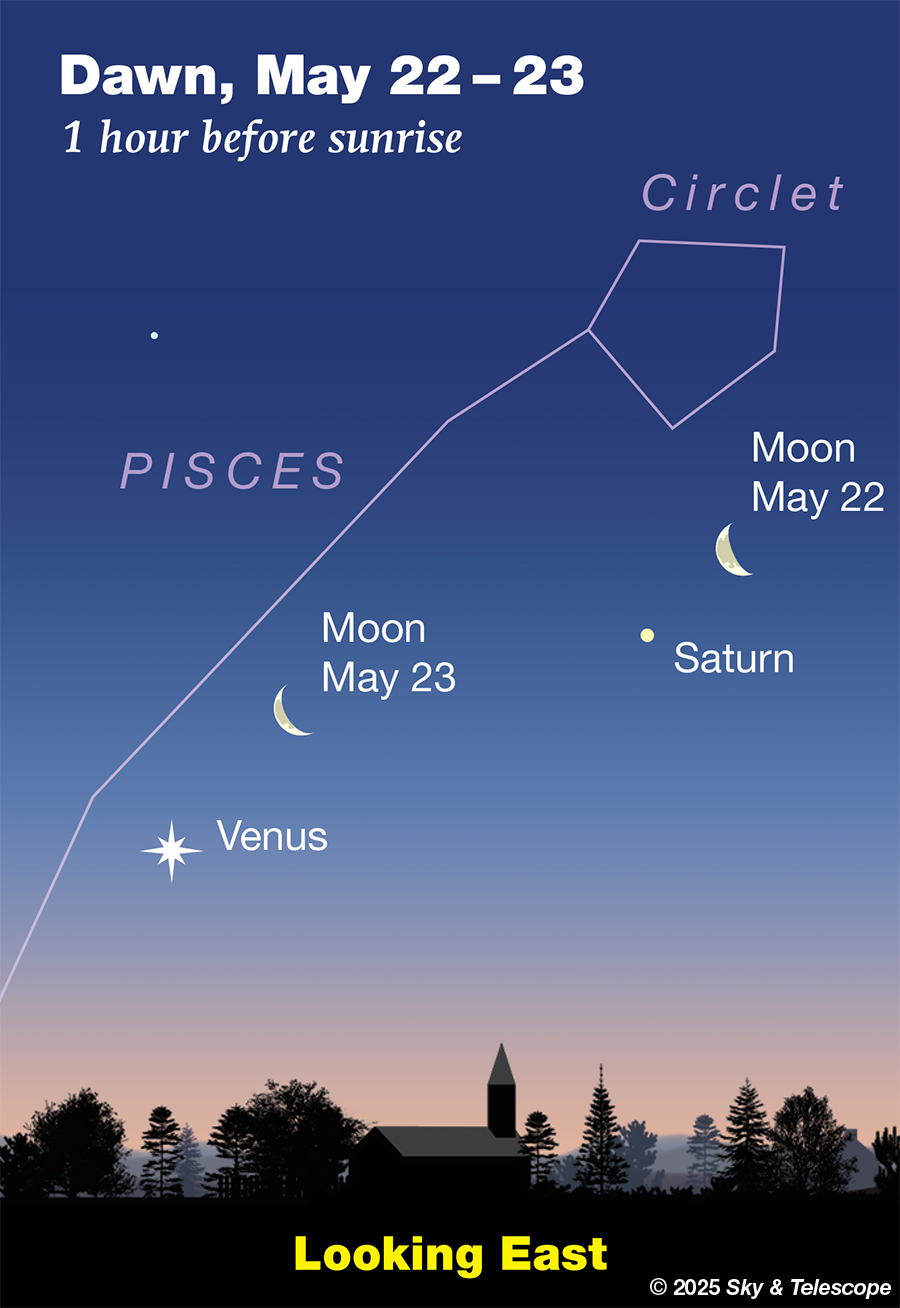

■ Early in dawn the next two mornings, the fickle Moon trades a dim partner for a bright one, as shown below.

THURSDAY, MAY 22

■ Have you ever seen even one star of Centaurus? Alpha Centauri, famous and bright, never gets above the horizon unless you’re as far south as San Antonio or Orlando (latitude 29° N). But Theta Centauri, shining at a respectable 2nd magnitude, makes it above your south horizon anywhere in the continental United States.

But you have to know where and when to look.

In late May, the time comes right after the end of twilight. And the place? Theta Centauri is almost three fists (27°) lower left of Spica, and just a bit farther (32°) lower right of Antares. You’ll need an open view very low there in the south; the farther north you are, the lower. Binoculars will help through light pollution near your south horizon, and/or if Theta Cen is so low that atmospheric extinction dims it a lot. Catch it and that’s one more constellation, or at least a piece of one, to add to your life list.

■ Do say hello to the waning crescent Moon over Venus early tomorrow morning, as shown above. They’ll be 6° or 7° apart for North America.

FRIDAY, MAY 23

■ Zero-magnitude Vega dominates the east-northeast these evenings. Look for its little constellation Lyra hanging down from it. The most familiar part of Lyra is a small, almost-equilateral triangle with Vega as its top corner, and a larger parallelogram hanging to the lower right from the triangle’s bottom corner. The bottom two stars of the parallelogram, Beta and Gamma Lyrae, are the two brightest stars of the pattern after Vega.

Akira Fujii

Most of the time Beta and Gamma are almost indistinguishable in brightness: Gamma is visual magnitude 3.25 and Beta is 3.4. But Beta is a famous eclipsing variable, one of the first discovered. Look up at those two enough times, and sooner or later you will catch Beta very obviously dimmer than Gamma, at its minimum brightness of mag 4.3. More often you’re likely to catch it somewhere in between, when the difference is clearly apparent but not as striking.

SATURDAY, MAY 24

■ Can you see the big Coma Berenices star cluster? Does your light pollution really hide it, or do you just not know exactly where to look? It’s 2/5 of the way from Denebola (Leo’s tail tip) to the end of the Big Dipper’s handle (Ursa Major’s tail tip). Its brightest members form an inverted Y. The entire cluster is about 4° or 5° wide — a big, dim glow in a fairly dark sky. It nearly fills a binocular view.

SUNDAY, MAY 25

■ Bright Capella sets low in the northwest fairly soon after dark these evenings (depending on your latitude). That leaves Vega and Arcturus as the brightest stars in the evening sky. Vega shines in the east-northeast. Arcturus is very high toward the south.

A third of the way from Arcturus down to Vega look for semicircular Corona Borealis, with 2nd-magnitude Alphecca as its one moderately bright star.

Two thirds of the way from Arcturus to Vega is the dim Keystone of Hercules. It’s now lying almost level. Use binoculars or a telescope to examine the Keystone’s top edge. A third of the way from its left end to the right is 6th-magnitude M13, one of Hercules’s two great globular star clusters. In binoculars it’s a tiny glowing cotton ball. A 4- or 6-inch scope begins to resolve some of its speckliness. Located 22,000 light-years away far above the plane of the Milky Way, it consists of several hundred thousand stars in a swarm about 140 light-years wide.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury is hidden deep in the sunrise.

Venus and Saturn appear low in the eastern dawn. They both rise around the very beginning of morning twilight: about two hours before sunrise. But Venus, magnitude –4.6, shines 230 times brighter than Saturn! Which is a weak magnitude +1.1.

Binoculars will help locate Saturn 12° upper right of Venus on the morning of May 17th (by about a fist at arm’s length), as shown at the top of this page. Their separation widens to 18° by May 24th.

Mars (magnitude 1.1, in Cancer) glows high in the southwest in the evening. It’s the orange dot almost 2/3 of the way from Pollux & Castor to Regulus. By comparison, Regulus is magnitude 1.3, Pollux is 1.1, and Castor is 1.6, respectively.

Now that Mars and Pollux are the same brightness, it’s an ideal time to compare their colors. Mars is more strongly tinted than pale yellow-orange Pollux, a type G8 giant star.

Farther below Mars shines Procyon, magnitude +0.4.

Mars continues to recede into the distance as Earth pulls ahead of it in our faster orbit around the Sun. In a telescope Mars is now only 6 arcseconds in diameter, a fuzzy blob. Can you can detect that it’s slightly gibbous?

Jupiter (magnitude –1.9, in Taurus) shines low in the west during twilight and sets around twilight’s end. It’s between Taurus’s two horntip stars, Beta Tauri to its upper right and fainter Zeta Tauri much closer to its lower left. They’re magnitudes 1.6 and 3.o.

Uranus is hidden in conjunction with the Sun.

Neptune, a mere 8th magnitude, lurks hidden in the dawn background of Saturn.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time minus 4 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

For the attitude every amateur astronomer needs, read Jennifer Willis’s Modest Expectations Give Rise to Delight.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas, in either the original or Jumbo Edition. Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, and 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as many more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used.

The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (with 201,000+ stars to magnitude 9.5 and 14,000 deep-sky objects selected to be detectable by eye in large amateur telescopes), and Uranometria 2000.0 (332,000 stars to mag 9.75, and 10,300 deep-sky objects). And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the new Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Do learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

— John Adams, 1770