FRIDAY, JUNE 27

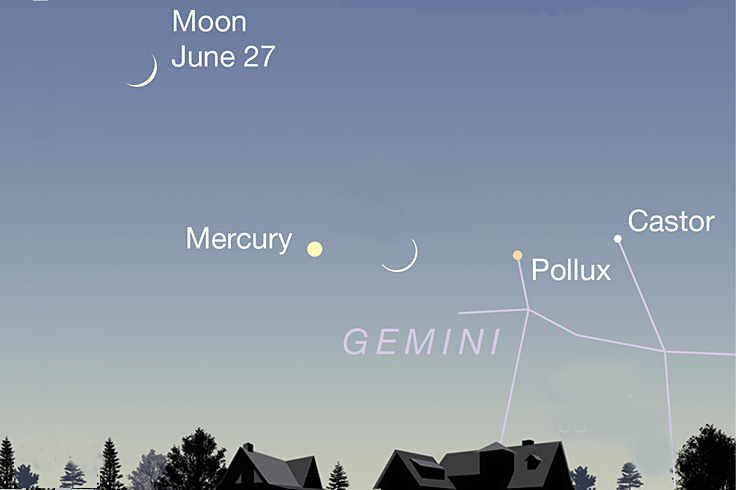

■ As twilight fades, spot the thin crescent Moon in the west-northwest as shown below. Look for Mercury to its lower right by about a fist at arm’s length. Mercury has been fading and is now magnitude +0.2. A week from now it will be only +0.6.

■ This is the time of year when the two brightest stars of summer, Arcturus and Vega, shine equally high overhead shortly after dark: Arcturus toward the southwest, Vega toward the east. Both are magnitude 0.

Arcturus and Vega are 37 and 25 light-years away, respectively. They represent the two commonest types of naked-eye star: a yellow-orange K giant and a white main-sequence A star. They’re 150 and 50 times brighter than the Sun, respectively — which, combined with their nearness, is why they dominate the evening sky.

Vega’s white has just a touch of icy blue. Arcturus is pale yellow-orange: a summery ginger-ale color. Do their colors stand out a little better for you in the deep blue of late twilight than in full dark? They seem to for me. Binoculars, of course, always make star colors much more evident.

SATURDAY, JUNE 28

■ Dangling down from Vega are stars of the little constellation Lyra, forming a small triangle and parallelogram. Vega is the brightest of the triangle, which is about the size of a thumbtip at arm’s length. The parallelogram hangs from the triangle’s lowest point.

The two stars forming the bottom of the parallelogram are Beta and Gamma Lyrae, Sheliak and Sulafat. They’re currently lined up almost vertically when you face them. Beta is the one on top.

Beta Lyrae is an eclipsing binary star. Compare it to Gamma whenever you look up at Lyra. For much of the time Beta is only a trace dimmer than Gamma. Eventually, however, you’ll catch Beta when it is quite obviously dimmer than usual.

The orbital period of this interacting binary is just 1.4 hours short of exactly 13 days. So expect its behavior to nearly repeat every two-weeks-minus-one-day throughout a given year’s observing season. Beta Lyrae’s exact brightness varies continuously, as shown in this light curve (V magnitude) courtesy of the AAVSO:

SUNDAY, JUNE 29

■ During and after late dusk, the crescent Moon hangs close to Mars in the west. For much of North America they’ll be 1° or less apart.

■ Vega is also the top star of the enormous Summer Triangle holding sway over the eastern sky after dark. Lower left of Vega by about two fists at arm’s length is Deneb. Three fists lower right of Vega is the third star of the Summer Triangle, Altair.

With the Moon now gone, you can see the Milky Way (if you’re not too light-polluted) running grandly just inside the Triangle’s bottom edge. This stretch of the Milky Way includes the Cygnus Star Cloud, one of one of its most star-rich regions. When we look toward Cygnus, we’re looking downstream through the local arm of our galaxy.

That’s also the direction we’re flying at 220 kilometers per second in the Sun’s orbital motion around the Milky Way.

■ In early dawn Monday morning, Venus inhabits Taurus in the vicinity of the Pleiades and Aldebaran as shown below.

MONDAY, JUNE 30

■ After nightfall, look due south for orange Antares nearly on the meridian. Around and upper right of Antares are the other, whiter stars forming the distinctive pattern of upper Scorpius. The rest of the Scorpion runs down from Antares toward the horizon, then left.

Three doubles at the top of Scorpius. The head of Scorpius — the near-vertical row of three stars upper right of Antares — stands nearly vertical. The top star of the row is Beta Scorpii or Graffias: a fine double star for telescopes, separation 13 arcseconds, magnitudes 2.8 and 5.0.

Akira Fujii took this photo before Delta Scorpii entered its historic brightening.

Just 1° below it is the very wide naked-eye pair Omega1 and Omega2 Scorpii. They’re 4th magnitude and ¼° apart. Binoculars show their slight color difference; they’re spectral types B9 and G2.

Upper left of Beta by 1.6° is Nu Scorpii, separation 41 arcseconds, magnitudes 3.8 and 6.5. In fact it’s a telescopic triple. High power in good seeing reveals Nu’s brighter component itself to be a close binary, separation 2 arcseconds, magnitudes 4.0 and 5.3, aligned almost north-south.

TUESDAY, JULY 1

■ Titan casts its shadow on Saturn tonight. Every 15 years Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, repeatedly crosses Saturn’s face from Earth’s viewpoint — and, more visibly, cast its tiny black shadow onto Saturn’ globe. A new series of these events is under way. They will continue every 16 days until October.

Tonight Titan’s shadow crosses Saturn from 7:40 to 13:03 UT July 2nd (UT date). That’s from 3:40 a.m. to 9:03 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time July 2nd; 12:40 a.m. to 6:03 a.m. PDT. Remember, Saturn only rises around midnight or 1 a.m. local time and doesn’t get high into good seeing until just before the beginning of dawn. Nearly all of North America now gets a chance. See Bob King’s Titan Shadow Transit Season Underway.

WEDNESDAY, JULY 2

■ First-quarter Moon (exact at 3:30 p.m. EDT). After sunset the Moon hangs between Spica to its left and Gamma Virginis, a telescopic double star, to its upper right.

THURSDAY, JULY 3

■ More Scorpius: To the right of Antares is that roughly vertical row of Beta, Delta, and fainter Pi Scorpii. The middle one, Delta Sco, is the brightest — obviously so. But it didn’t used to be. It used to be like Beta.

Delta is a strange variable star, a fast-rotating blue subgiant throwing off luminous gas from its equator. Assumed for centuries to be stable, Delta doubled in brightness unexpectedly in summer 2000, then dipped down and up again several times from 2005 to 2010, and has remained essentially steady at peak brightness (magnitude 1.7) ever since.

Delta has a smaller orbiting companion star that was suspected to trigger activity at 10.5-year intervals. Astronomers watched to see whether the system would have another flareup around 2022, when the companion star made its third pass by the primary star since 2000. But nothing happened. No one knows what might happen next, or when.

FRIDAY, JULY 4

■ If you have a dark enough sky, the Milky Way now forms a magnificent arch high across the whole eastern sky after nightfall is complete. It runs all the way from below Cassiopeia in the north-northeast, up and across Cygnus and the Summer Triangle in the east, and down past the spout of the Sagittarius Teapot in the south.

SATURDAY, JULY 5

■ The Big Dipper, high in the northwest after dark, is beginning to turn around to “scoop up water” through the evenings of summer and early fall.

■ Look low in the northwest or north at the end of these long summer twilights. Would you recognize noctilucent clouds if you saw them there? They’re the most astronomical of all cloud types, what with their extreme altitude and, sometimes, their formation on meteoric dust particles. They used to be rare, but they’ve become more common in recent years as Earth’s atmosphere changes. See Bob King’s Nights of Noctilucent Clouds.

SUNDAY, JULY 6

■ This evening the waxing gibbous Moon shines in the head of Scorpius, with Delta Scorpii above it and Antares to its left. And tonight the Moon’s dark limb occults Pi Scorpii, magnitude 2.9, for observers nearly all across North and Central America. See the July Sky & Telescope, page 48.

Map and timetables. The first two tables, with predictions for many cities, are long. The first table gives the times of the star’s disappearance behind the Moon’s dark limb; the second gives its reappearance out from behind the Moon’s bright limb (much less observable). Scroll to be sure you’re using the correct table; watch for the new heading as you scroll down. The first two letters in each entry are the country abbreviation (CA is Canada, not California). The times are in UT (GMT) July 7th. UT is 4 hours ahead of Eastern Daylight Time, 5 hours ahead of CDT, 6 ahead of MDT, and 7 ahead of PDT.

For instance: Use the first table to see that for Chicago, Pi Scorpii disappears at 11:40 p.m. July 6th Central Daylight Time, when the Moon is 17° high in the south-southwest (azimuth 204°).

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury is fading and starting to sink back down into the glow of sunset. The crescent Moon points the way to it on Friday the 27th, as shown at the top of this page.

Venus, brilliant at magnitude –4.2, rises above the east-northeast horizon about a half hour before the first glimmer of dawn. Venus climbs higher until the dawn sky grows too bright for it. In a telescope Venus’s shrinking globe (now only about 18 arcseconds pole to pole) has become gibbous, 63% sunlit.

Mars is drawing farther away from Regulus low in the west right after dusk. They’re 6° apart on Friday June 27th and widen to 10° apart by Friday July 4th, with Regulus moving farther away to Mars’s lower right.

In a telescope Mars is just a tiny shimmering blob 5 arcseconds wide. Don’t bother.

Jupiter remains out of sight in conjunction with the Sun.

Saturn (magnitude +1.0, at the border of Aquarius and Pisces) rises around midnight or 1 a.m. daylight-saving time. Just before and during early dawn, it’s about five or six fists upper right of Venus.

The best time to try a telescope on Saturn is just as dawn is beginning, when Saturn has had time to get about 35° high but still stands out against a reasonably dark sky. You may be surprised by the look of Saturn; its rings are nearly edge-on to us this year.

Uranus is still unobservably low as dawn begins.

Neptune, a telescopic “star” at magnitude 7.9, lurks in Saturn’s background just 1° from it. Catch this outermost major planet before dawn begins by using the finder chart for Neptune with respect to Saturn in the June Sky & Telescope, page 51. With a pencil, put a dot on the path of each planet for your date. Get everything planned out and ready to go the evening before, so that dawn doesn’t overtake you.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time minus 4 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

For the attitude every amateur astronomer needs, read Jennifer Willis’s Modest Expectations Give Rise to Delight.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas, in either the original or Jumbo Edition. Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, and 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as many more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used.

The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (with 201,000+ stars to magnitude 9.5 and 14,000 deep-sky objects selected to be detectable by eye in large amateur telescopes), and Uranometria 2000.0 (332,000 stars to mag 9.75, and 10,300 deep-sky objects). And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the new Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Do learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

— John Adams, 1770