FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 6

■ The biggest well-known asterism in the sky is the Winter Hexagon. It fills the heavens toward the east and south these dark evenings.

Start with brilliant Sirius at its bottom. Going clockwise from there, go upper left to Procyon, then Pollux and Castor (ignoring brilliant Jupiter). Then straight up to 2nd-magnitude Menkalinan and brilliant Capella nearly overhead, then down to Aldebaran high in the south-southwest, then down to Orion’s bright foot Rigel, and back to Sirius. Betelgeuse shines inside the Hexagon, off center.

Since then Jupiter has moved farther from Pollux and Castor; Jupiter is still retrograding, moving west against the stars. It will resume direct motion eastward on March 11th.

The Hexagon is somewhat distended. But if you draw a line through its middle from Capella down to Sirius, at least the “Hexagon” is fairly symmetric with respect to that long axis.

Now take the line from Aldebaran to Capella, turn it to go from Aldebaran to Betelgeuse instead, and the Winter Hexagon becomes a variant: the Heavenly G.

■ And to go deep into the Hexagon with a large telescope these moonless evenings, use a deep sky atlas with Andy Edelen’s “Galaxy Hopping in the Winter Hexagon” in the February Sky & Telescope, page 22.

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 7

■ Orion is high in the southeast right after dark. Left of it is the constellation Gemini, with bright Jupiter in its middle now and headed up by Castor and Pollux at far left. The stick-figure Twins are still lying on their sides.

Well below their legs is bright Procyon. Standing 4° above Procyon is 3rd-magnitude Gomeisa, Beta Canis Minoris, the only other easy naked-eye star of Canis Minor. The Little Dog is seen in profile, but only his back and the top of his head. Procyon marks his rump, Beta CMi is the back of his neck, and two fainter stars just above that are the top of his head and his nose. Those last two are only 4th and 5th magnitude, respectively. Binoculars help through light pollution.

■ Then the waning gibbous Moon rises around 11 p.m. tonight, with Spica 2° to its upper right. They draw farther apart until Spica is lost in Sunday’s brightening dawn.

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 8

■ The last-quarter Moon rises around 1 a.m. tonight. (It’s exactly last quarter at 7:43 a.m. EST Monday morning.) If you’re up in the cold hour before the start of dawn, spot Antares and the other stars of upper Scorpius a fist or two to the Moon’s lower left, and Spica about twice as far to the Moon’s upper right.

MONDAY, FEBRUARY 9

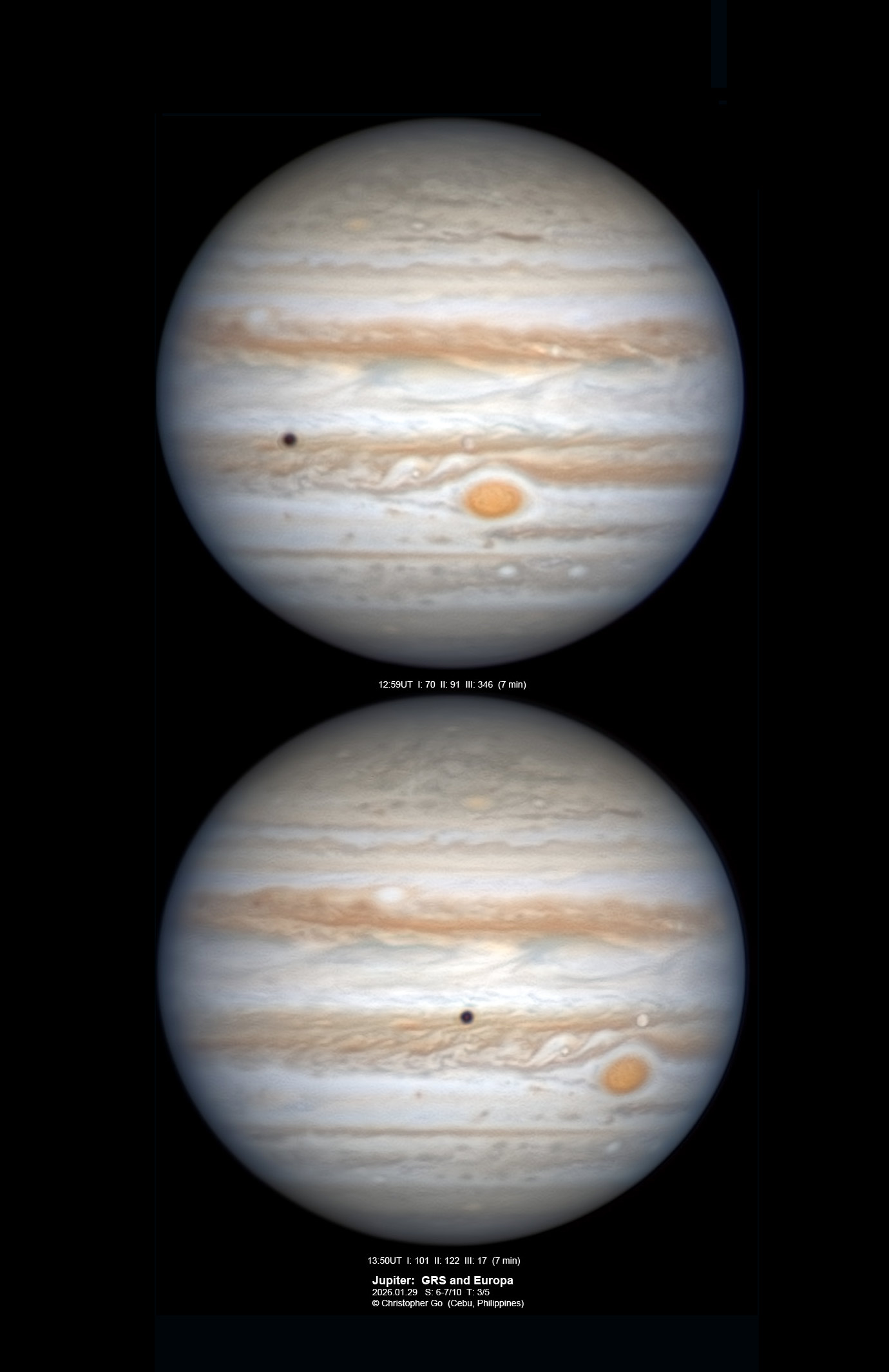

■ Jupiter’s Great Red Spot should cross Jupiter’s central meridian (the line down the center of its disk from the pole to pole) around 9:46 p.m. EST (6:46 p.m. PST). The Spot should be visible almost as easily for about an hour before and after in a good 4-inch telescope, if the atmospheric seeing is sharp and steady.

The Red Spot transits about every 9 hours 56 minutes. But not quite like clockwork! It drifts east or west in Jupiter’s atmosphere somewhat irregularly. A change often becomes detectable to visual transit timers over a span of some months. Our transit-time predictions are based on fairly recent observations, but don’t be surprised if the Red Spot has taken it into its head to move a few minutes off schedule.

February’s complete list of predicted Red Spot transit times, good worldwide, is in the February Sky & Telescope, page 50.

■ In the darkness before dawn Tuesday morning, the waning Moon shines in the head of Scorpius. If the edge of the Moon were a bow shooting an arrow, it would be aiming at Antares.

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 10

■ Right after night is completely dark this week, the W of Cassiopeia shines high in the northwest, standing almost on end. Near the zenith is Capella.

The brightest star about midway between Cassiopeia and Capella (and a little off to the left as you face Cassiopeia) is Alpha Persei, magnitude 1.8. It lies on the lower-right edge of the Alpha Persei Cluster: a large, elongated, very loose swarm of fainter stars about the size of your thumbprint at arm’s length. At least a dozen are 6th magnitude or brighter, bright enough to show quite well in binoculars.

Alpha Per, a white supergiant, is a true member of the group and is its brightest light. It and the rest are about 570 light-years away.

■ Before dawn tomorrow morning, the waning Moon hangs under Antares. Every month the Moon passes Antares 3½ to 4 days after passing Spica. (The average time for this is 3¾ days, but there are variations.)

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 11

■ Have you ever carefully compared the colors of Betelgeuse and Aldebaran? Can you detect any difference in their colors at all? I can’t, really. Yet Aldebaran is spectral type K5 III, often called an “orange” giant, while Betelgeuse, spectral type M1-M2 Ia, is usually called a “red” supergiant. Their temperatures are indeed a bit different: 3,900 Kelvin and 3,600 Kelvin, respectively.

A complication: Betelgeuse is brighter, and to the human eye the colors of bright objects appear, falsely, to be desaturated: looking paler (whiter) than they really are. You can get a slightly better read on the colors of bright stars by defocusing them, to spread their light over a larger area of your retina.

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 12

■ By 9 p.m. or so, the Big Dipper stands on its handle in the northeast. In the northwest, Cassiopeia also stands on end (its brighter end) at about the same height.

Between them is Polaris, about as bright as most of the Big Dipper’s stars.

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 13

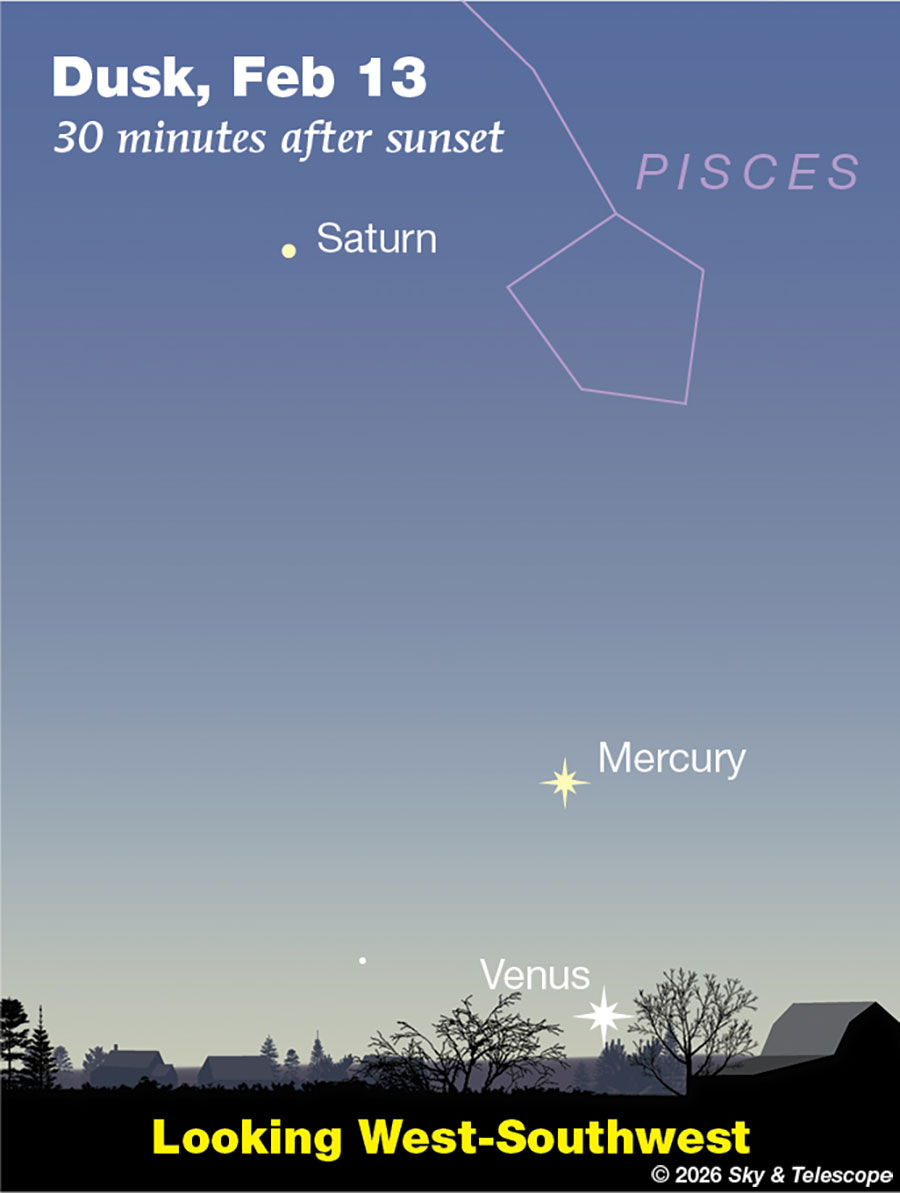

After sunset, keeping watch in the bright twilight low in the west-southwest for Mercury, magnitude –1, and extremely low Venus, magnitude –3.9. Venus is barely beginning its evening apparition of 2026, as shown below. This evening, Venus and Mercury are 8° apart.

Saturn, much dimmer, comes into view later in twilight.

■ Orion stands his highest in the south by about 8 p.m., looking smaller than you’ll remember him appearing early in the winter when he was low. You’re seeing the “Moon illusion” effect. Constellations, not just the Moon, look bigger when they’re low.

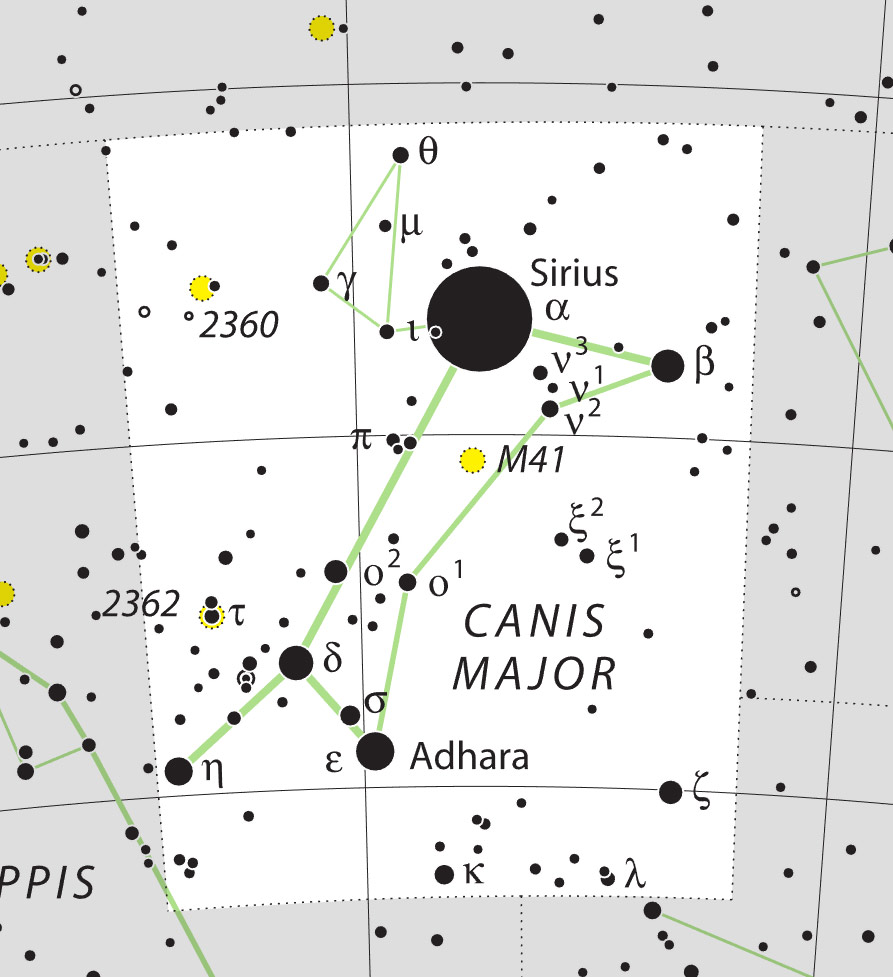

■ After dinnertime Sirius the Dog Star, the brightest star of Canis Major, blazes in the southeast. Look lower left of Orion.

In a dark sky with lots of stars, Canis Major’s points can be connected to form a convincing dog seen in profile. He’s currently standing on his hind legs, facing right. Sirius shines on his chest like a dogtag, to the right or lower right of his faint, triangular head, as shown below.

But through the light pollution where most of us live, only the five brightest stars of Canis Major are easily visible. These form the Meat Cleaver. Sirius is the cleaver’s top back corner. Its blade faces right (from Beta, β, to Epsilon, ε) and its short handle points lower left (ending in Eta, η).

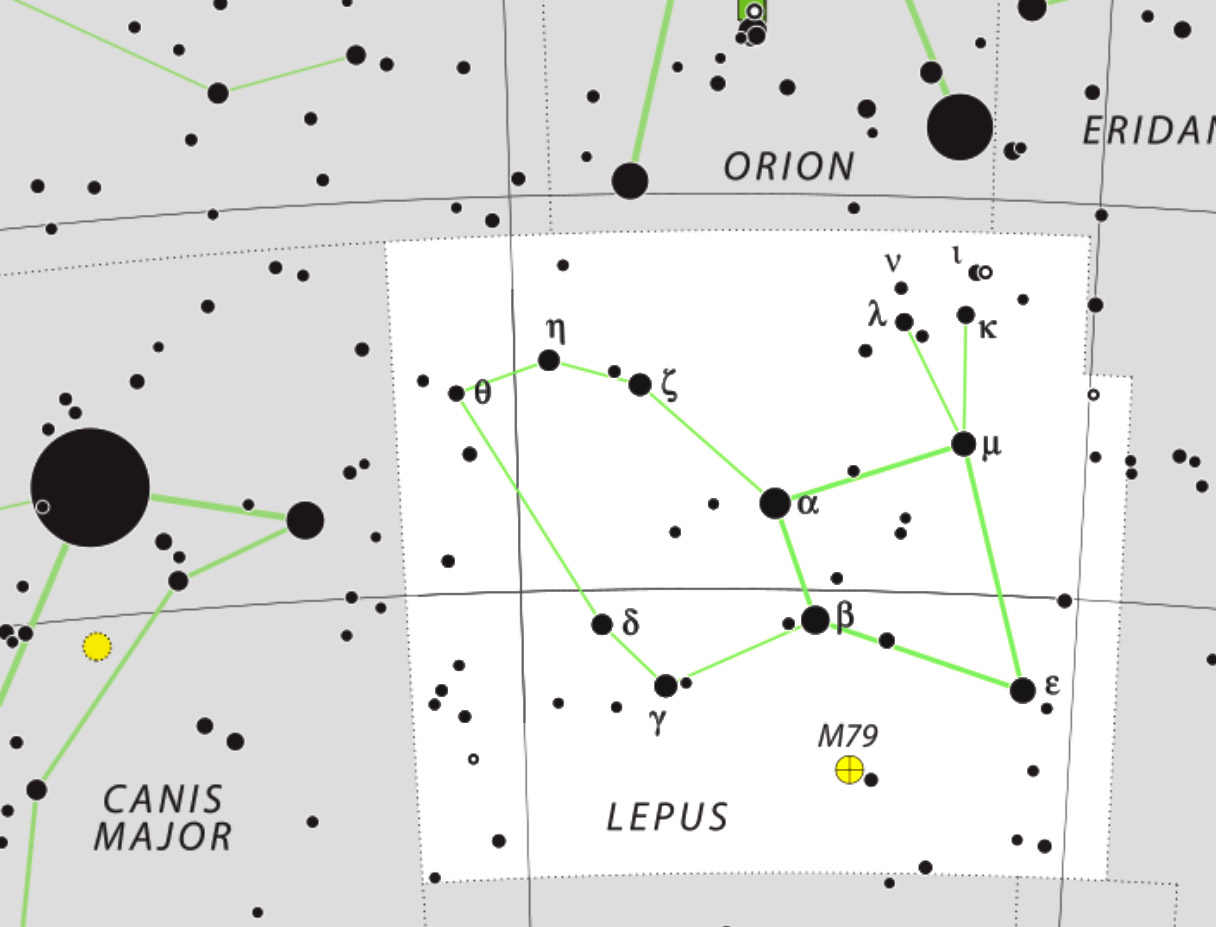

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 14

■ Below Orion and to the right of Sirius hides Lepus the Hare. Like Canis Major, this is a constellation with a connect-the-dots that really looks like what it’s supposed to be. He’s a crouching bunny, with his nose pointing lower right, his faint ears extending up toward Rigel (Orion’s brighter foot), and his body bunched to the left. His brightest two stars, 3rd-magnitude Alpha and Beta Leporis, form the back and front of his neck, as shown below.

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 15

■ A fast-creeping red dwarf. Have you ever seen a red dwarf star? These are the most common stars in space, but they’re so intrinsically dim that not one of them is among the 6,000 pinpoints visible to the naked eye on even the darkest nights. One of the nearest and brightest red dwarfs lies just 3° west of Procyon, nicely placed these winter evenings. It’s Luyten’s Star, also known as GJ 273, and at visual magnitude 9.9 it’s in range of small to medium telescopes. Use the finder charts with Bob King’s article Catch Luyten’s Star.

This humble object is very close to us as stars go, only 12.3 light-years away, so it is also a high proper motion star; it creeps across its celestial backdrop by 3.7 arcseconds per year. This means that a careful visual telescope user might detect its motion in as little as about 3 years, writes King, “depending on its proximity to field stars and the making and breaking of distinctive alignments with other stars.” He suggests, “Make an initial observation, note the position in a sketch, map or photo, and then return a couple years later. Hey, no hurry.”

To locate and identify Luyten’s Star with King’s charts you’ll need to be good at telescopic star-hopping. This is an essential skill for any amateur astronomer to develop so you don’t get lost in space. See How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope, and expect a certain amount of frustration at first. Everyone goes through this. Don’t give up.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury is becoming spottable low in the west-southwest about 30 or 40 minutes after sunset. Binoculars will help. Mercury gets a little higher every evening, while remaining a bright magnitude –1 all week.

Venus, way down below Mercury, is much brighter at magnitude –3.9. But it has to with contend with worse horizon obstructions and strong atmospheric extinction.

It’s also creeping up much more slowly day by day. Venus is 5° below Mercury on Friday February 6th, and 8° below it a week later on the 13th. Good luck.

Mars is out of sight behind the glare of the Sun.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.6) shines in the middle of Gemini. Spot it very high in the east-southeast as twilight fades; it’s the first “star” of the evening. Jupiter shines highest in the south by about 9 p.m. In a telescope it’s still 45 arcseconds wide. See “Jupiter Rules!” in the January Sky & Telescope, page 48, with a map of its dark belts and bright zones.

Jupiter’s clouds always appear less bright toward the limb, making a bright-surfaced satellite like Europa stand out more distinctly when it’s near the beginnings and ends of its transits.

Saturn (magnitude +1.1, in Pisces) is the brightest dot low in the west-southwest at nightfall, lower left of the Great Square of Pegasus. It sets a little more than an hour after dark.

In a telescope Saturn’s rings are still very thin but gradually opening up, now tilted 2° or 3° to our line of sight. The rings’ thin black shadow on Saturn’s globe is slowly widening too. But the telescopic seeing so low will be very poor! Get your telescope on Saturn as early in twilight as you can find it naked-eye.

Uranus (magnitude 5.7, in Taurus 5° south of the Pleiades) is very high in the southwest these evenings. At high power in a telescope it’s a tiny but non-stellar dot, 3.6 arcseconds wide. You’ll need a detailed finder chart to identify it among similar-looking faint stars, such as the chart in last November’s Sky & Telescope, page 49.

Neptune is a telescopic “star” of magnitude 7.9 near declining Saturn. Time to let it go for the season!

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Standard Time (EST) is Universal Time minus 5 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

For the attitude every amateur astronomer needs, read Jennifer Willis’s Modest Expectations Give Rise to Delight.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll want a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas, in either the original or Jumbo Edition. Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, and 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as many more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used.

The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum Deep-Sky Atlas (with 201,000+ stars to magnitude 9.5 and 14,000 deep-sky objects selected to be detectable by eye in very large amateur telescopes), and Uranometria 2000.0 (332,000 stars to mag 9.75, and 10,300 deep-sky objects).

Read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to electronic charts on your phone or tablet — which many observers find handier and more versatile, if perhaps less well designed, than charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. It was my bedside reading for years. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the new Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Well, I used to say this:

“Not for beginners, I don’t think, unless you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning how to explore through the sky yourself. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, ‘A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.’ Without these, ‘the sky never becomes a friendly place.’ “

But, things change. The technology has continued to improve and become more user-friendly — particularly with software that can now recognize any star field to determine exactly where the telescope is pointed — finally bypassing all aiming imperfections in the mount, tripod, gears, bearings and other mechanics, or in the user’s skill in setting up.

The latest revolution is the rise of small, imaging-only “smartscopes.” These take advantage of not only today’s pointing technology, but also the vastly better capabilities of imaging chips and image processing compared to the human retina and visual cortex. The most sophisticated image stacking and processing can also come built right in. The result is decent deep-sky imaging from shockingly small, low-priced units. The image may be viewable on your phone or computer as it builds up in real time. Some can directly enable contributions to citizen-science projects.

Smartscopes are changing the hobby at the entry level. For more on this revolution see Richard Wright’s “The Rise of the Smart Telescopes” in the November 2025 Sky & Telescope. And read the magazine’s review of this especially small one.

If you get a larger, more conventional computerized scope that allows direct visual use, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

— John Adams, 1770