FRIDAY, DECEMBER 12

■ Have you ever watched Sirius rise? Find an open view right down to the east-southeast horizon, and watch for this brightest star to come up about two fists at arm’s length below Orion’s vertical Belt. Sirius comes up around 8 or 9 p.m. now, depending on your location.

About 15 minutes before Sirius-rise, a lesser star comes up barely to the right of where Sirius will appear. This is Beta Canis Majoris, or Mirzam. Its name means “the Announcer,” and what Mirzam announces is Sirius. You’re not likely to mistake them; the second-magnitude Announcer is only a twentieth as bright as the King of Stars soon to make its royal entry.

When a star is very low it tends to twinkle slowly, so0metimes flashing vivid colors. Sirius is bright enough to show these effects well, especially with binoculars.

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 13

■ The Geminid meteor shower should peak late tonight. The sky is dark and free of moonlight until the waning crescent Moon rises around 2 or 3 a.m., and even then its modest moonlight is no big problem. The Geminids are usually the richest shower of the year. Moreover, this year the shower’s broad peak, many hours long, is expected to be centered on 3 a.m. Eastern time; midnight Pacific (8:00 UT). This is ideal for North America. So late tonight, you might see one or two meteors a minute on average under a wide-open dark sky.

In early evening the meteors will be fewer, but those that do appear will be long, graceful Earth-grazers skimming far across the top of the atmosphere. As the hours pass and the shower’s radiant (near Castor in Gemini) rises higher in the east, the meteors will become shorter and more numerous.

Layer up even more warmly than you think you’ll need, and a thick blanket on top of that will help. Remember, under a clear open sky you will have radiational cooling!

Find a dark spot with a wide-open sky and no local lights to get in your eyes. Lie back in a reclining lawn chair and gaze up into the stars. The best direction to watch is wherever your sky is darkest, probably straight up.

For more see Bob King’s article Geminid Meteor Shower Peaks December 13-14.

■ As for that waning crescent Moon (25% illuminated) climbing the sky before dawn, you’ll find that it’s accompanied by “springtime” Spica, as shown below.

And then as early dawn brightens, Mercury (magnitude –0.5) will rise some four fists lower left of the Moon. Much fainter Beta Scorpii (total mag +2.5) will shimmer weakly 0.6° lower right of Mercury. For this you’ll likely need those binoculars.

And, Beta Sco is a wide telescopic double star: magnitudes 2.6 and 4.9, separation 13.5 arcseconds. What might Mercury and the star pair look like through a telescope in the rough seeing so near the horizon? Use low power to get the planet and the pair in view at the same time.

Even if you can’t make out Beta’s fainter companion, have you ever before seen anything of Scorpius in December?

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 14

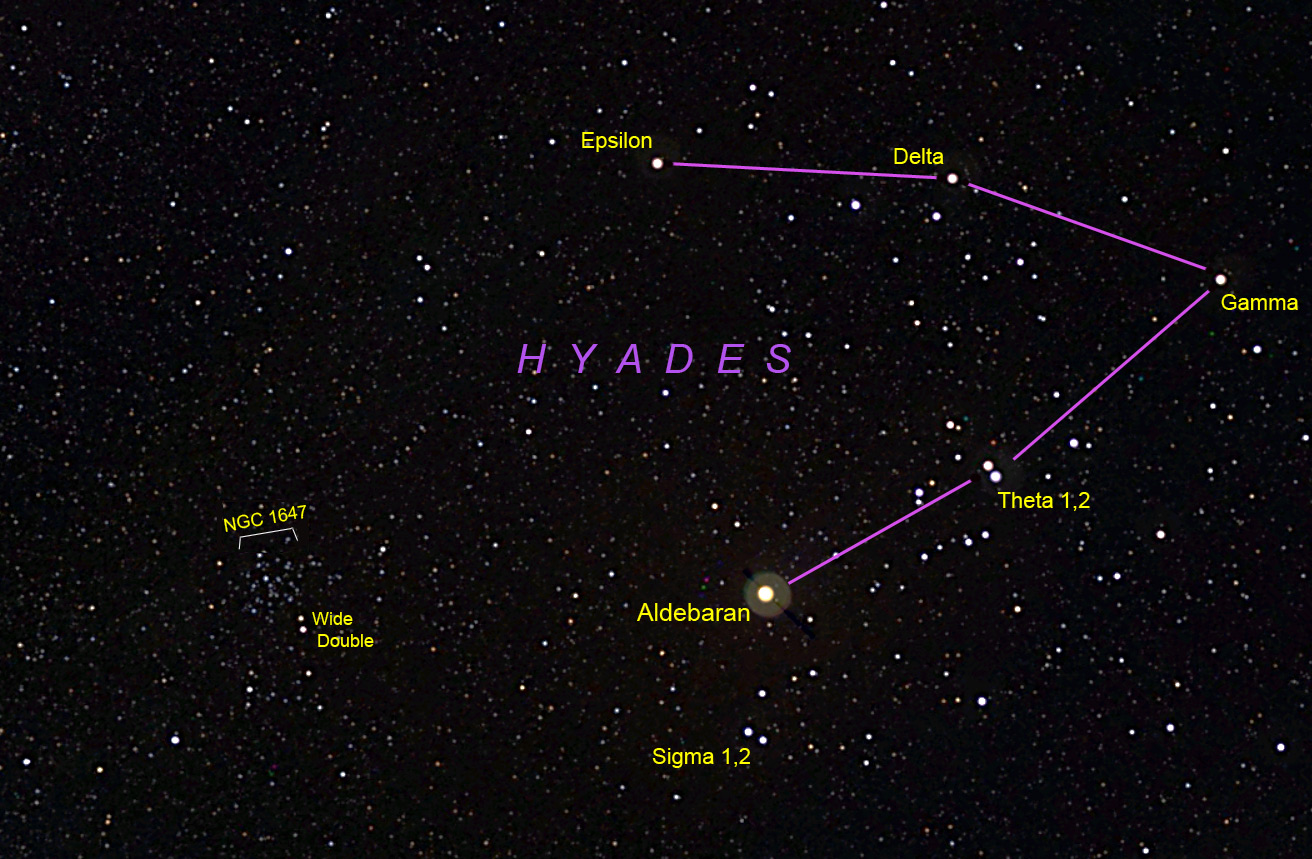

■ As we near the end of the year, brilliant Capella is already high in the northeast after dark. Look almost three fists to its right, and there’s the Pleiades star cluster. A fist or so below the Pleiades shines orange Aldebaran.

Just upper right of Aldebaran are the scattered stars of the Hyades cluster, larger and dimmer than the Pleiades. The brightest Hyades plus Aldebaran form a V, which you’ll always find lying on its side on December and January evenings.

■ After the Pleiades and Hyades, what’s the next most noted star cluster in Taurus? Maybe it’s dim, loose NGC 1647, between the horns of Taurus just a few degrees left Aldebaran and the Hyades. Matt Wedel, Sky & Telescope‘s Binocular Highlights columnist, called it “a wonderful object for binoculars” in a really dark sky. . . which most of us don’t have. But you may (or may not) find the cluster to be at least detectable in good, largish binoculars on a moonless night. It’s about ½° wide, and its brightest dozen or so stars are only 9th and 10th magnitude. Averted vision will help. Using 10×50 binoculars, I can see maybe the barest hint of it through my fairly bright suburban sky (Bortle Scale 6).

This closeup view is 5½° tall, about the size of the view in 10x binoculars.

At least the cluster’s location is easy enough to find: It forms a roughly equilateral triangle with Aldebaran and the other tip of the Hyades V. The cluster is actually 1° southeast of (currently lower left of) the point that would make the equilateral triangle perfect.

Just off the cluster’s south edge you’ll find a brighter “fine optical double star,” Matt writes, very wide and unequal, both yellow-orange, magnitudes 6.0 and 7.5, separation 5 arcminutes. The faint one is over the bright one during the cold evenings at this time of year.

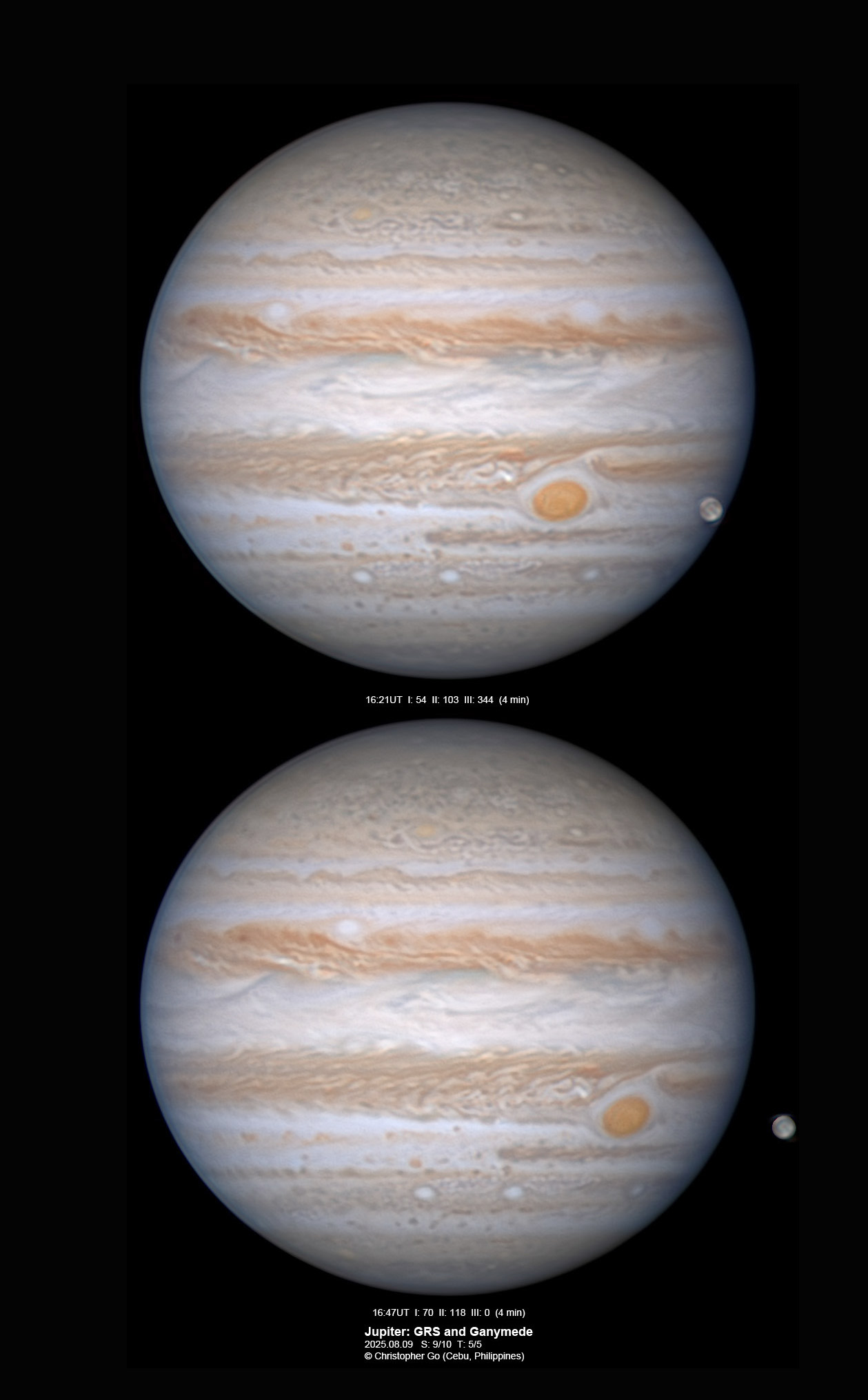

■ Jupiter’s Great Red Spot should cross Jupiter’s central meridian (the imaginary line down the center of the planet’s disk from pole to pole) around 7:59 p.m. EST. The spot should be visible almost as easily for an hour before and after, in a good 4-inch telescope if the atmospheric seeing is sharp and steady.

The Red Spot transits about every 9 hours 56 minutes. But not quite like clockwork! It drifts east or west in Jupiter’s atmosphere somewhat irregularly. A change often becomes detectable to visual transit timers over a span of some months. Our transit-time predictions are based on fairly recent observations, but don’t be surprised if the Red Spot has taken it into its head to move a few minutes off schedule.

■ Then, Io reappears out from behind Jupiter at 8:55 p.m. It will appear to slowly bud off Jupiter’s eastern limb.

MONDAY, DECEMBER 15

■ The “Summer” Triangle is sinking low in the west to northwest, and Altair is the first of its stars to go (for mid-northern skywatchers).

Start by spotting bright Vega, magnitude zero, the brightest star in the northwest right after dark. The brightest one above Vega is Deneb. Altair, the Triangle’s third star, is farther to Vega’s left or lower left. How late into the night, and into the advancing season, can you keep Altair in view?

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 16

■ The Pleiades cluster shines very high in the southeast after dinnertime, no bigger than your fingertip at arm’s length. How many Pleiads can you count with your unaided eye? Take your time and keep looking. Most people with good or well-corrected vision can count 6. With extra-sharp vision, a good dark sky, and a steady gaze, you may be able to make out 8 or 9. Binoculars can show dozens.

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 17

■ Face southwest this week, look very high up, and there’s the Great Square of Pegasus tilted onto on one corner. It’s a little bigger than your fist at arm’s length. Its stars are 2nd and 3rd magnitude. Brighter Saturn shines lower left of the Square when you’re facing southwest.

■ Algol should be at its minimum brightness, magnitude 3.4 instead if its usual 2.1, for a couple hours centered on 10:28 p.m. EST (7:28 p.m. PST). Comparison-star chart.

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 18

■ This is the time of year when M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, passes your zenith right after dark (if you live in the mid-northern latitudes). The exact time depends on your longitude. Binoculars will show M31 just off the knee of the Andromeda constellation’s stick figure; see the big evening constellation chart in the center of Sky & Telescope.

Lie on your back with the binocs and look straight up. M31 crosses smack through your zenith if you’re at 41° north latitude.

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 19

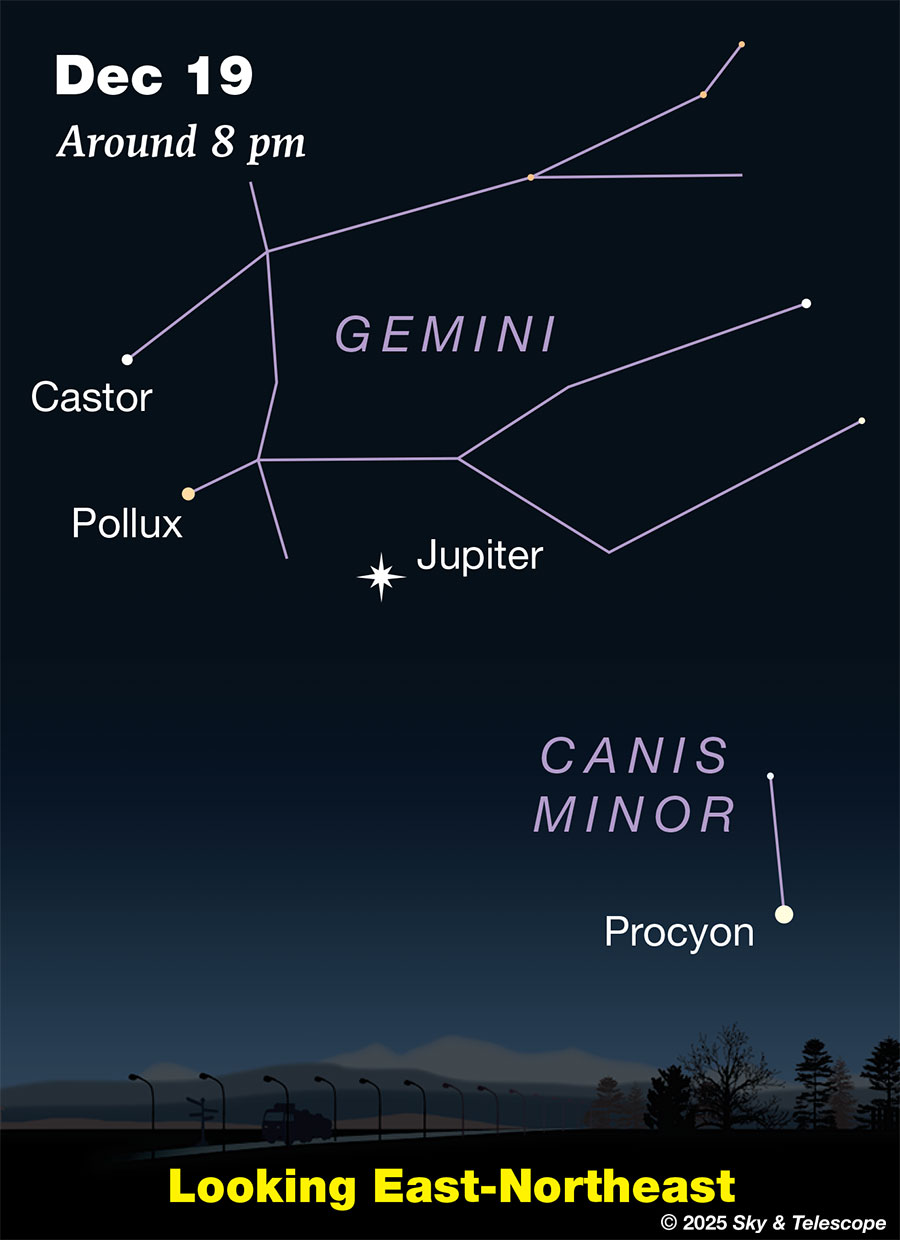

■ Jupiter doesn’t move against the starry background as fast as the inner planets do, but move it does. Currently it’s moving westward (“retrograde”) on its way to opposition on January 10th. Compared to a week ago, notice that Jupiter has advanced well off the line between Pollux and Procyon, as shown below.

■ New Moon (exact at 8:43 p.m. EST).

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 20

■ Sirius and Procyon in the balance: Sirius, the brilliant Dog Star, sparkles low in the east-southeast by 8 or 9 p.m. Procyon, the Little Dog Star, shines to its left in the east about two fist-widths at arm’s length from Sirius.

But directly left? That depends! If you live around latitude 30° (Tijuana, Austin, New Orleans, Jacksonville), the two canine stars will be at the same height above your horizon soon after they rise. If you’re north of that latitude, Procyon will be higher. If you’re south of there, Sirius will be the higher one. Your eastern horizon tilts differently with respect to the stars depending on your latitude. Because the Earth is round.

■ Algol should be at its minimum brightness for a couple hours centered on 7:17 p.m. EST.

■ You are remembered, Carl Sagan (November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996).

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 21

■ These are the longest nights of the year (in the Northern Hemisphere). Winter begins today at the solstice, at 10:03 a.m. EST. This is the moment when the Sun halts its southward journey in Earth’s sky and begins its six-month return back northward, with the promise of a new spring and summer to come.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury is still visible low in the dawn, holding its brightness at magnitude –0.5. But it’s slowly getting lower, rising now a bit after the first hint of dawnlight. Look for it low in the east-southeast as dawn grows. Best view might be 50 or 60 minutes before sunrise. At magnitude –0.5 all week, Mercury far outshines any other point in its area.

On the morning of the 14th, the morning of the Geminid meteor peak, use binoculars or a wide-field telescope to catch the unequal double star Beta Scorpii nosing up from the horizon just 0.6° lower right of Mercury, as told at the bottom of December 13 above.

Venus and Mars are hidden behind the glare of the Sun.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.6, in eastern Gemini) rises in the east-northeast about an hour after full dark. It dominates the eastern sky as the evening proceeds, then the high southeast. Castor and Pollux shine nearby. Jupiter is highest and telescopically sharpest in the south in the hours after midnight; it will reach opposition January 10th. It’s now a big 45 arcseconds wide, almost as large as it will be at opposition (47 arcseconds).

Go writes, “Conditions were perfect! Details inside the Great Red Spot are well resolved. There is a bright outbreak on the wake of the GRS [small, white, just left of the Great Red Spot]. The chimney above the GRS is open.” The chimney is the whitish plume from the Red Spot Hollow that frequently breaks through, or maybe covers, the tan belt-material north of it. “The North Equatorial Belt is narrow in this region. Ganymede is also well resolved with surface details.”

Go uses a 14-inch telescope from the low-latitude Philippines, a top-end planetary video camera, and state-of-the-art frame stacking, de-rotation of Jupiter, and image processing drawing on many years of experience.

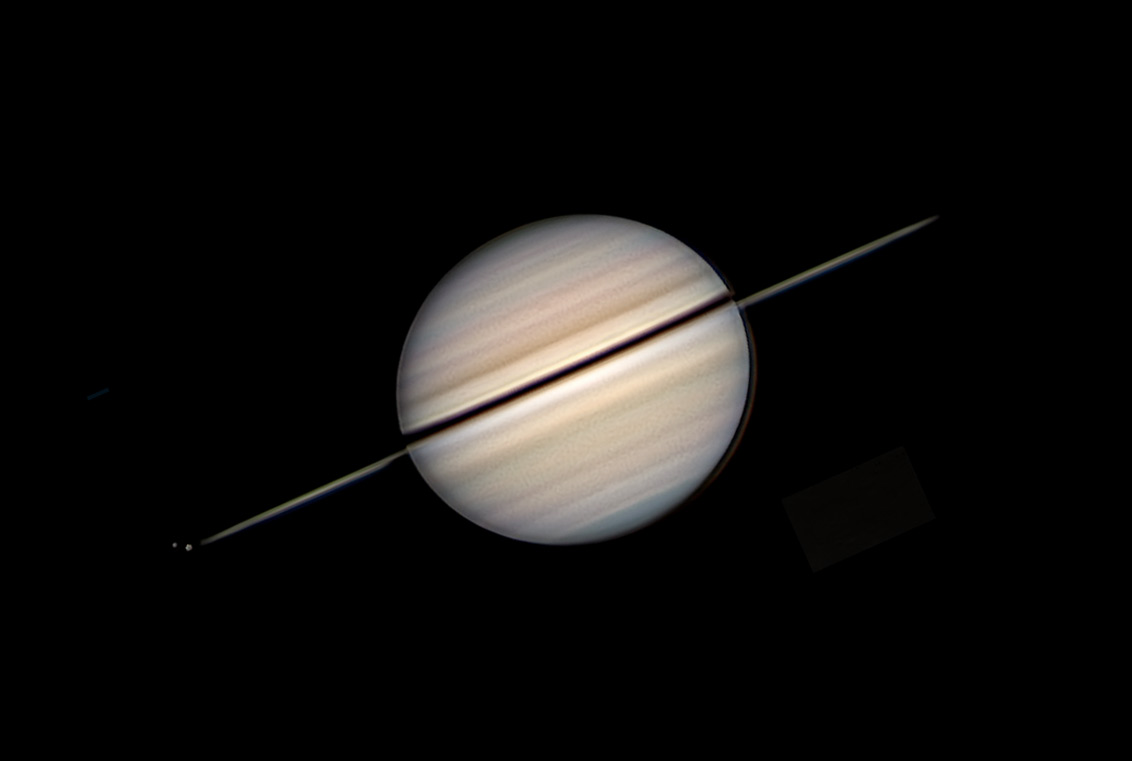

Saturn (magnitude +1.1, at the Aquarius-Pisces border) is the brightest dot high in the south at nightfall, below the Great Square of Pegasus. It gets lower in the southwest through the evening and sets around midnight.

In a telescope Saturn’s rings remain very close to edge on, tilted less than 1° to our line of sight. This continues for the rest of December. For more goings-on at Saturn during this rare time, see Bob King’s See Saturn’s Rings at Their Thinnest. He suggests using the rings’ near-absence to try to add inner Mimas to your log of Saturnian moons. Or at least Enceladus, which I repeatedly glimpsed in a 6-inch reflector during a previous thin-rings season. King includes a timetable of Mimas’s greatest elongations that happen when Saturn is high in the dark for North America. As for Enceladus’s greatest elongations, you can find them by playing with Sky & Telescope‘s interactive Saturn’s Moons calculator. Run the hours and minutes forward and backward to see when Enceladus (“E”) is farthest out at a time when Saturn will be high in darkness for you.

Uranus (magnitude 5.6, in Taurus 5° south of the Pleiades) is well up by 7 or 8 p.m. At high power in a telescope it’s a tiny but definitely non-stellar dot, 3.8 arcseconds wide. You’ll need a detailed finder chart to identify it among similar-looking faint stars; turn to the November Sky & Telescope, page 49.

Neptune is a telescopic “star” of magnitude 7.8, a dim speck just 2.3 arcseconds wide 4° northeast of show-stealing Saturn. For Neptune you’ll need an even more detailed finder chart.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Standard Time (EST) is Universal Time minus 5 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

For the attitude every amateur astronomer needs, read Jennifer Willis’s Modest Expectations Give Rise to Delight.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll want a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas, in either the original or Jumbo Edition. Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, and 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as many more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used.

The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum Deep-Sky Atlas (with 201,000+ stars to magnitude 9.5 and 14,000 deep-sky objects selected to be detectable by eye in very large amateur telescopes), and Uranometria 2000.0 (332,000 stars to mag 9.75, and 10,300 deep-sky objects).

And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to electronic charts on your phone or tablet, which many observers find handier and more versatile, if perhaps less carefully designed, than charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. It was my bedside reading for years. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the new Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Well, this is what I used to say:

“Not for beginners, I don’t think, unless you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning how to explore through the sky yourself. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, ‘A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.’ Without these, ‘the sky never becomes a friendly place.’ “

Well, things change. The technology has continued to improve and become more user-friendly — particularly with software that can now, amazingly, recognize any telescopic star field to determine exactly where the telescope is pointed — finally bypassing all imperfections in the mount, tripod, gears, bearings and other mechanics, or in the user’s skill in setting up.

The latest revolution is the rise of small, imaging-only “smartscopes.” These take advantage of not only today’s pointing technology, but also the vastly better capabilities of imaging chips and processing compared to the human retina and visual cortex. The most sophisticated image stacking and processing can come built in. The result is reasonably capable deep-sky imaging from shockingly small, low-priced units. The image may be viewable on your phone or computer as it builds up in real time. Small smartscopes can enable contributions to serious citizen-science projects.

These are changing the hobby at the entry level. For more on this revolution see Richard Wright’s “The Rise of the Smart Telescopes” in the November 2025 Sky & Telescope. And read the magazine’s review of this especially tiny one.

If you get a larger, more conventional computerized scope that allows direct visual use, do make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

— John Adams, 1770

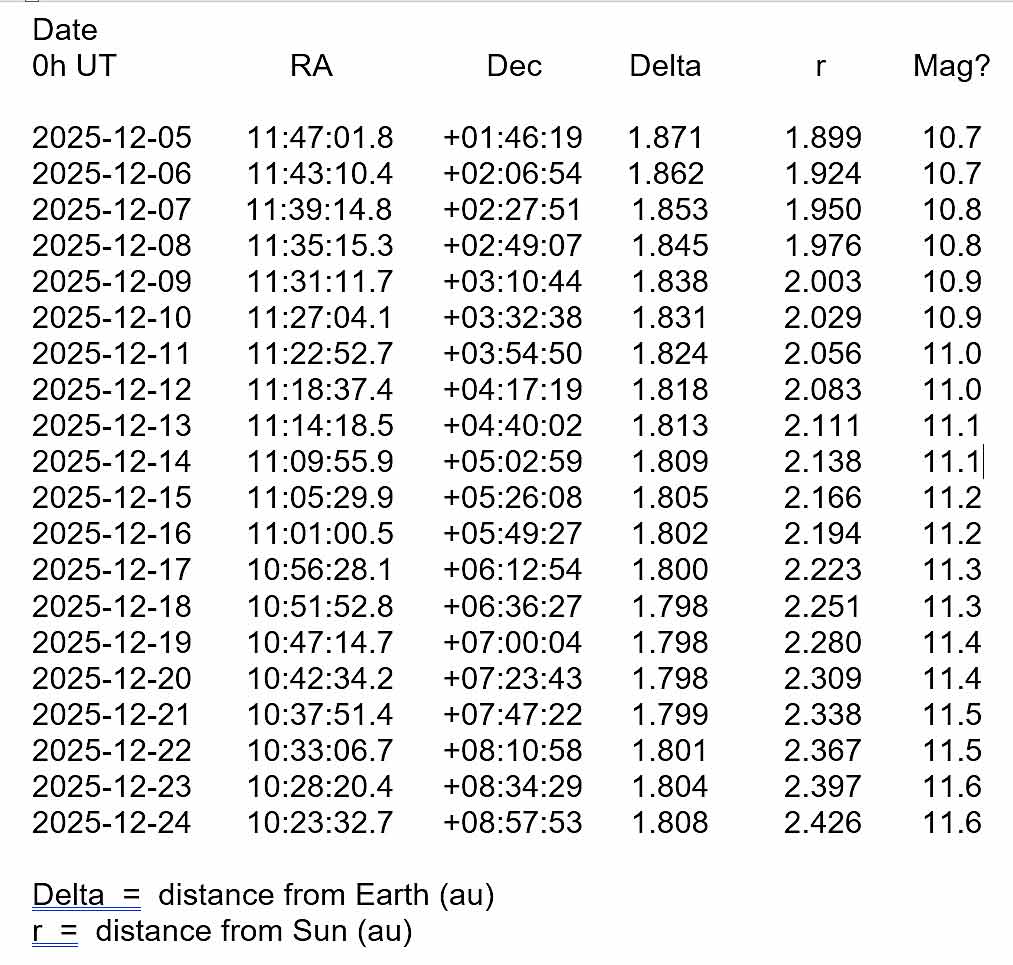

Ephemeris for Comet 3I ATLAS: