FRIDAY, AUGUST 8

■ Week after week, distant little Mars stays practically on station at the same height low over your western landscape in twilight. Mars apparitions always drag on and on toward their end, but this year Mars is especially reluctant to exit. It will continue to set right around the end of twilight all the way into early fall (for skywatchers at mid-northern latitudes), and it won’t reach conjunction with the Sun until the beginning of 2026.

SATURDAY, AUGUST 9

■ The two brightest stars of summer are Vega, overhead shortly after nightfall, and Arcturus shining in the west. Draw a line down from Vega to Arcturus. A third of the way down, the line crosses the dim Keystone of Hercules. Two thirds of the way down it crosses the dim semicircle of Corona Borealis with its one modestly bright star, 2nd-magnitude Alphecca or Gemma. If you’ve been watching for the next explosion of T Coronae Borealis, the recurrent nova has now gone unexploded for well over a year of built-up expectations.

■ Vega and the Keystone’s star closest to it form an equilateral triangle with 2nd-magnitude Eltanin to their north: the nose of Draco the Dragon. Eltanin is the brightest star of Draco’s quadrilateral head. He’s eyeing Vega.

SUNDAY, AUGUST 10

■ At this time of year the Big Dipper scoops down in the northwest during evening, as if to pick up the water that it will dump from high overhead in the evenings of next spring.

■ Are you seeing any Perseid meteors yet? Despite the moonlight? The Perseids are active at noticeable levels for many days before and several days after their peak, which this year is predicted for the night of August 12-13.

MONDAY, AUGUST 11

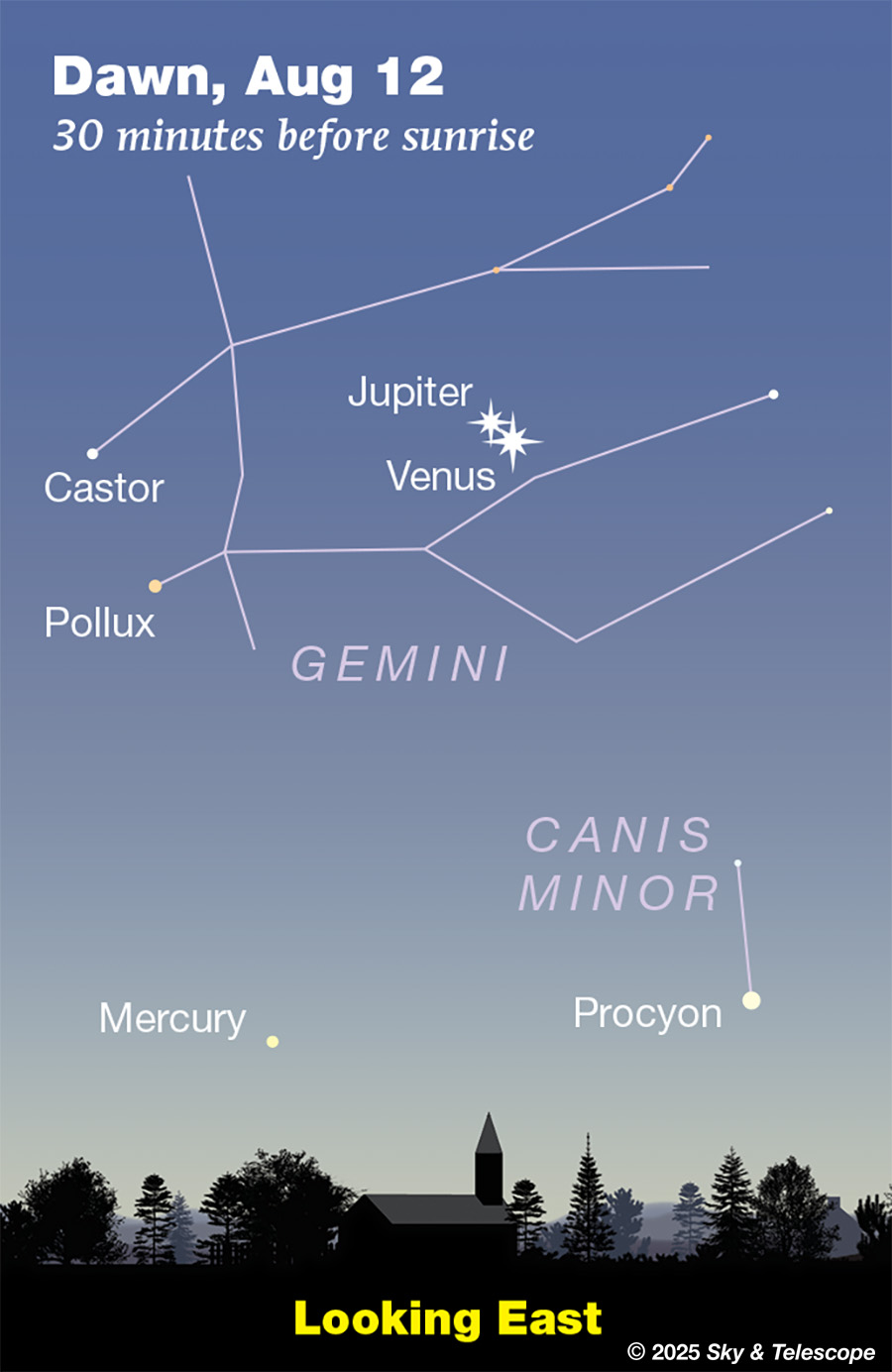

■ Venus and Jupiter shine in conjunction, just 0.9° apart, in the east during early dawn Tuesday morning the 12th. In fact, they rise about an hour before dawn even begins if you have a good flat horizon to the east-northeast.

Think photo opportunity. Zoom in, frame the planets with interesting foreground, and brace your phone or camera firmly.

TUESDAY, AUGUST 12

■ Late tonight comes the predicted peak of the annual Perseid meteor shower. However, a bright waning gibbous Moon shines through all of the dark hours, washing the sky with moonlight that will hide many or most of the meteors. But a few of the brightest ones always shine through . . . if you’re just a bit lucky. See Bob King’s Moon or Not, the Perseid Meteor Shower Is On!

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 13

■ The Perseids are still active late tonight. That’s a hint. Even though the moonlight is still there too.

■ The W of Cassiopeia, tilted not very much, is nicely up in the northeast these evenings, above Perseus. The upper, right-hand side of the W is its brightest side. Watch Cas rise higher and straighten upright through the next hours and the next months.

THURSDAY, AUGUST 14

■ Vega passes its closest to overhead around 10 p.m. now, depending on how far east or west you are in your time zone.

Deneb passes the zenith two hours after Vega.

FRIDAY, AUGUST 15

■ Last-quarter Moon tonight (exact at 1:12 a.m. Saturday morning EDT). The Moon rises around 11 or midnight daylight-saving time, with the Pleiades following it up about 20 minutes behind. As the Moon gets higher, look for the Pleiades about 6° to its lower left. By the beginning of dawn the Moon and Pleiades are very high in the southeast, now level with each other and only about 3° or 4° apart.

SATURDAY, AUGUST 16

■ Different people have an easier or harder time seeing star colors, especially subtle ones. To me, the tints of bright stars stand out a little better in a sky that’s neither black nor light-polluted gray, but the deep blue of late twilight.

For instance, the two brightest stars of summer are Vega, overhead after dark, and Arcturus shining in the west. Vega is white with just a touch of blue. Arcturus is a yellow-orange giant. Do their colors stand out a little better for you in late twilight? What about deeper orange Antares, lower in the south-southwest? Could this be a color-contrast effect of seeing yellow, orange, or orange-red stars on a blue background?

SUNDAY, AUGUST 17

■ Whenever Vega crosses nearest your zenith, as it does soon after dark now, you know that the Sagittarius Teapot is at its highest due south.

Two hours later, when Deneb passes the zenith, it’s the turn of little Delphinus and boat-shaped Capricornus down below it to stand at their highest due south.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury is still very low in the glow of sunrise. Wait till next week.

Venus and Jupiter shine together in the east before and during dawn! These are the two brightest planets, currently magnitudes –4.0 and –1.9 respectively. In fact they’re two brightest (permanent) celestial objects after the Sun and Moon. They clear the east-northeast horizon an hour or more before dawn begins.

On Saturday morning August 9th Venus and Jupiter are still 3° apart. They reach conjunction just 0.9° apart on Tuesday morning the 12th. By Saturday the 16th they’ll be back to 4° apart, now with Jupiter on top.

Both are about at their farthest from Earth, however, so they’re not much in a telescope. Especially at their low altitude, which means seeing them through thick, shimmery air.

Mars, a weak magnitude 1.6 in the head of Virgo, still glimmers very low in the west in evening twilight. Binoculars will help. Mars sets at twilight’s end. It too is about at its farthest from Earth.

Don’t confuse orange Mars with twinklier, whiter Spica about two fists to its upper left. See the top of this page.

Saturn (magnitude +0.8, in Pisces) rises due east around the end of twilight. It’s lower right of the Great Square of Pegasus, which now stands on one corner diamond fashion. The Square’s lower left side points diagonally down almost straight to Saturn.

But the best time to observe Saturn with a telescope is in early morning hours when it’s high toward the south. We see Saturn’s rings almost edge-on this year, and the Sun shines on them from nearly our direction also. So the rings and their shadow form a super-thin black line along Saturn’s equator.

Uranus (magnitude 5.7, in Taurus near the Pleiades) rises around midnight and is high in the east before the beginning of dawn. In a telescope it’s a tiny but definitely non-stellar dot 3.6 arcseconds wide.

Neptune, a telescopic “star” at magnitude 7.8, lurks hardly more than 1° from Saturn in the early morning hours. Use the finder chart for Neptune with respect to Saturn in the June Sky & Telescope, page 51. With a pencil, put a dot on the path of each of the two planets for your date. Neptune is just 2.3 arcseconds wide.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time minus 4 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

For the attitude every amateur astronomer needs, read Jennifer Willis’s Modest Expectations Give Rise to Delight.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas, in either the original or Jumbo Edition. Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, and 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as many more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used.

The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (with 201,000+ stars to magnitude 9.5 and 14,000 deep-sky objects selected to be detectable by eye in large amateur telescopes), and Uranometria 2000.0 (332,000 stars to mag 9.75, and 10,300 deep-sky objects). And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet (which many observers find more versatile) as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the new Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Do learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

— John Adams, 1770