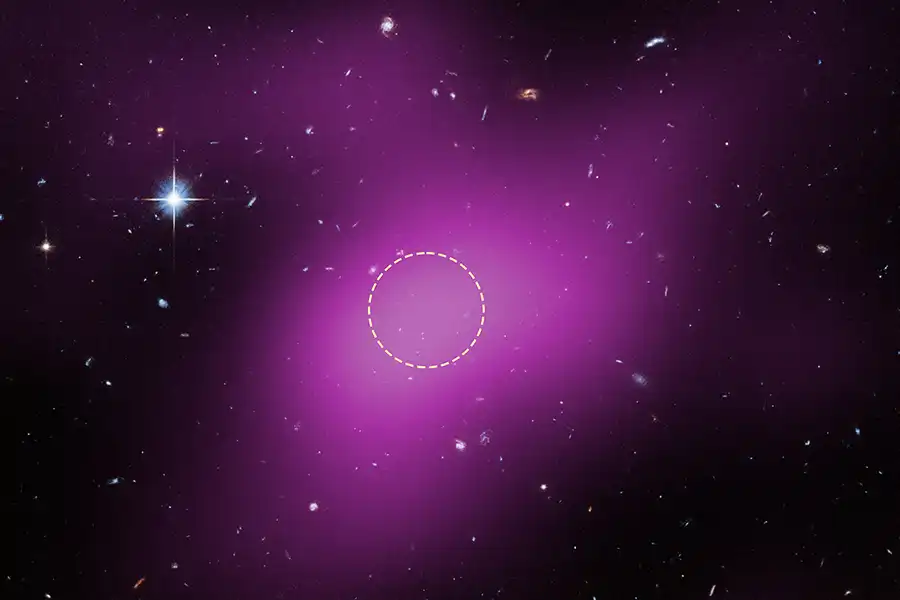

NASA, ESA. G. Anand (STScI), and A. Benitez-Llambay (Univ. of Milan-Bicocca); Image processing: J. DePasquale (STScI)

Every galaxy in the universe is anchored by a large, unseen halo of material that astronomers call dark matter. But what if there are halos in which galaxies never formed?

Now, astronomers have discovered one of those empty dark matter haloes, dubbed “Cloud 9.” Rather than your typical galaxy, brimming with stars, Cloud-9 is simply a cold cloud of hydrogen gas bound by dark matter’s invisible force.

“It’s basically a galaxy that wasn’t,” says Rachael Beaton (Space Telescope Science Institute), who announced the result in a press conference during the 247th American Astronomical Society meeting in Phoenix, Arizona. It should’ve formed stars to become “a galaxy like we know and love, but that didn’t happen,” she says.

The team observed Cloud 9 with multiple telescopes, finding around 1 million solar masses of neutral hydrogen. Since the cloud is too large to be held together with its own gravity, the team deduced that it’s probably underpinned by a dark matter halo, “the skeleton that galaxies form on,” Beaton says. The team estimates that around 5 billion solar masses of dark matter material are holding the cloud together.

These mysterious structures are called Reionization Limited Hydrogen I Clouds, or RELHICs. They are isolated clumps of hydrogen gas, theorized to have formed during reionization, an early cosmic epoch during which the first galaxies and stars began to shine.

“Cloud 9 is the most convincing candidate we have for a RELHIC — a pristine, dark matter structure that never formed stars,” says Alejandro Benítez-Llambay (University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy), a co-author on the paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“This is what makes Cloud-9 truly remarkable,” he says. “It isn’t just a serendipitous discovery or a cosmic anomaly.” RELHICs validate astronomers’ theories of dark matter and galaxy formation.

Relics of the Early Universe

Hydrogen gas only emits at low radio frequencies, and the Chinese Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) discovered Cloud 9 by its radio emission near the Messier 94 spiral galaxy. (The name refers to the object being the 9th discovered in FAST’s survey and doesn’t mean anything particular in Chinese culture.)

The team followed up with Green Bank Telescope and Very Large Array to confirm Cloud 9’s location and map the cool hydrogen gas in more detail. But none of the existing images in optical wavelengths showed any starlight. So the team turned to a more sensitive instrument to confirm Cloud 9’s starless nature: the Hubble Space Telescope. Yet still, they found absolutely nothing, confirming the cloud’s striking absence of stars.

Based on Hubble’s non-detection, the team estimated that at most, there could only be around 4,000 Suns’ worth of stellar material lurking in the cloud — far fewer stars than even the faintest dwarf galaxies.

“[The discovery] is plausible,” says Matthieu Schaller (Leiden Observatory), who was not involved in the study, “if it’s not a cloud in the Milky Way.”

Since the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate, the team measured the Cloud 9’s distance by observing its recessional speed. It’s receding at the same rate as the Messier 94 (M94) spiral galaxy, which is nearby on the sky, placing the cloud at 14 million light-years away. “But that is a distance which is too near to be very confident on,” says Schaller, who worked with Benítez-Llambay on the 2017 paper that first conceived of RELHICs. If Cloud 9 is instead near our own galaxy, then it could be an ordinary clump of gas.

So far, Cloud 9 appears to be a cosmic fossil, frozen in time before it could start to grow and form stars. The cloud’s existence can shed more light on how the first galaxies formed in dark matter halos — and in Cloud 9’s case, what went wrong.

Fated to be Starless

Most galaxies began forming during reionization. “Shortly after the Big Bang, the first stars and quasars flooded the universe with ultraviolet radiation, heating the intergalactic gas,” Benítez-Llambay says. Dark matter haloes had to be massive enough for their gravity to overcome the outward pressures of this heated gas, instead collapsing and cooling to form stars. On the other hand, the gravity of smaller haloes was too weak, so the heated gas simply dispersed into space.

“RELHICs are the rare systems caught in between,” says Benítez-Llambay. These clouds are “late bloomers,” he says; by the time they reached a sufficient mass to begin forming a galaxy, ultraviolet radiation from other newly formed galaxies had already warmed the gas up too much for it to collapse into stars. Yet the inward pull of dark matter managed to hold on to the hot primordial gas. “The system exists in a delicate balance,” he says.

“Today they are just massive enough to hold onto the gas against the ultraviolet heating, but not massive enough to force that gas to collapse and ignite stars,” Benítez-Llambay explains.

Cloud-9 might not always remain starless. It could merge with another halo to reach a critical mass “where gravity finally wins, causing the gas to collapse and ignite stars,” Benítez-Llambay says. On the flip side, the cloud could easily be dispersed entirely by interactions with other galaxies. In fact, the VLA data showed that the cloud’s outer layers have already been perturbed and tugged at by the nearby M94 spiral galaxy. If the two come any closer, wind and gas in M94’s surroundings could strip away Cloud 9’s gas entirely.

“I think that the argument they bring is fairly convincing,” Schaller says. He adds that with the distorted features revealed by the VLA observations, Cloud 9 is “not, maybe, as round as they could’ve wished” for a RELHIC. “But there could be good reasons for it,” he adds, accepting their explanation of stripping from M94: “It’s close to another galaxy, so maybe it gets deformed.”

RELHICs like these can also probe the very nature of dark matter itself. The prevailing theory of dark matter predicts that such starless haloes should exist. Finding Cloud 9 confirms that astronomers are on the right track.

Finding more RELHICs will help astronomers pin down the nature of dark matter, since different types of dark matter particles would result in different structures. For example, some scenarios produce a dense core at the center of the halos, which would in turn affect the density of hydrogen gas in the RELHICs. “They could be very nice laboratories for understanding the properties of dark matter,” Schaller says.

The team is attempting to map out where else these starless halos could be hiding in the local cosmic neighborhood using radio surveys, which could search for gas clouds too massive to be held together without dark matter. Follow-up observations with Hubble or the James Webb Space Telescope could also rule out even small numbers of stars.

Finding more RELHICs will help illuminate just how dark matter came together to form galaxies in the early universe — by revealing when it didn’t.