Sebastian Voltmer

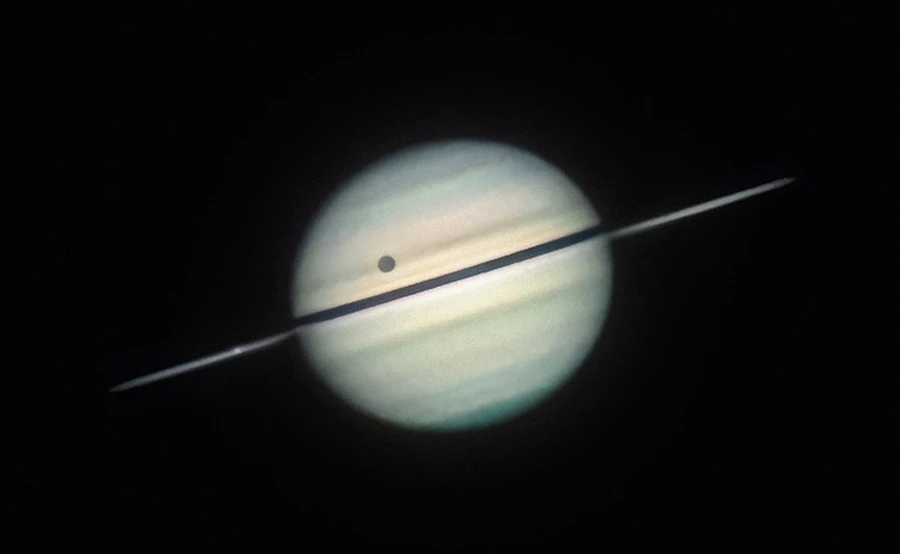

When Saturn’s rings turned edgewise on March 23rd, no one on the ground saw it happen. The planet was swamped by solar glare at the time. Amateur astronomers captured the first images of the rings’ return to view in mid-April, when they were inclined 1.1° with the south face open. For a time, orbital geometry caused the Sun to temporarily illuminate the north face when the opposing south face was tipped our way, making for an exceptionally dim ring presentation. The situation improved in May when the Sun’s light finally began to illuminate the south face.

Saturn’s orbital motion, combined with our changing view from planet Earth, which is tipped 2.5° relative to the Sun-Saturn plane, causes the rings to waver north and south for a time until they fully “commit” to opening. On July 7th, the ring plane fanned open to a maximum of 3.6°, then began slowly closing again. Minimum inclination of 0.37° (south face open) occurs on November 23rd. Thereafter, the rings steadily open until reaching a maximum inclination of 27° in 2032.

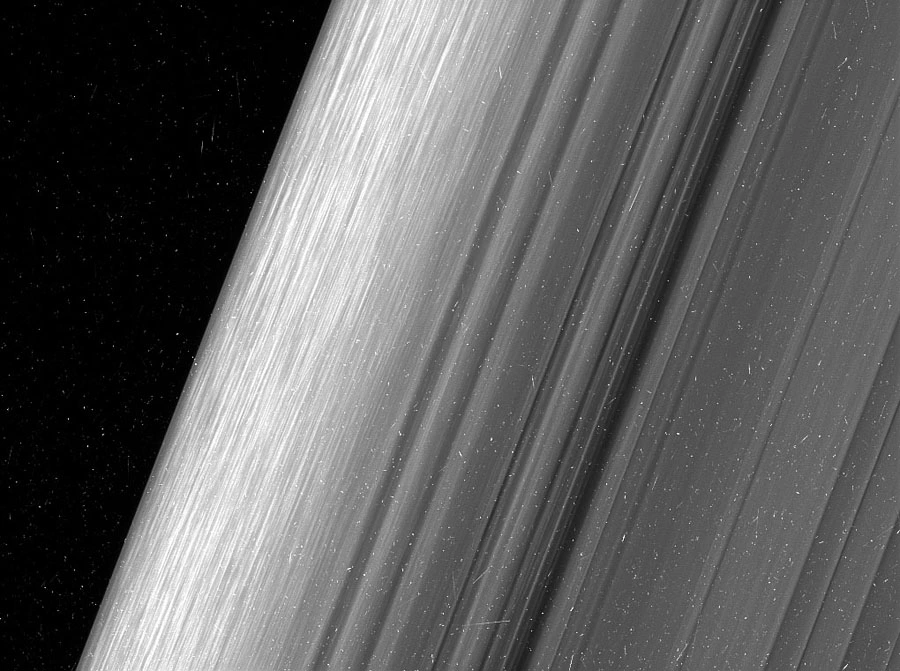

Much of the rings’ grandeur is currently hidden because they’re physically so thin — only about 10 meters (33 feet) thick on average — that when viewed nearly edge-on they resemble a feather’s edge instead of nest for the Saturnian globe. At this time, we can best appreciate how vanishingly thin they are. Using the mind’s eye and a few visual aids, let’s try to immerse ourselves inside them.

Imagine billions of scintillating miniature moonlets ranging in size from sand grains up to houses. Objects closer to Saturn would travel faster than those farther out, so that in total they would appear to spiral around the planet. Likely you’d see streams of material — with clumps here and there — alternating with zones or relative emptiness. The video above hints at what it might be like. Keep in mind the actual ice chunks would be irregular in shape and more widely separated, on average about 10 meters apart.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The best view might just be a short distance above the ring plane, where you could look out across an endless carpet of tumbling, rotating, reflective ice shards. Near you, the pieces would be fewer and farther apart. But they’d merge and overlap in the distance to create brilliant, densely textured bands. When facing the Sun’s direction I suspect it would leave a dull glitter path across the myriad ring bodies similar to the Moon’s reflection when rising over a lake of cloudy ice.

The next few weeks are the best time to see Saturn’s rings at their slivery thinnest this apparition. Since rings scatter light into the sky around the planet, it’s also an opportunity to hunt for the fainter moons that rarely escape its glare. Yes, the disk of Saturn will still throw out plenty of light. It can’t be avoided 100%, but you can hunt for these dim blips in two ways: keeping the planet just outside the field of view, or by inserting an occulting bar inside a high-magnification eyepiece and hiding Saturn behind it.

Stellarium

Besides nixing glare, keeping the planet out of view allows the eye to dark-adapt, the better to see close-in Mimas (magnitude 13.0), Enceladus (11.8), and Hyperion (14.3). Although the faintest of Saturn’s major moons, I’ve observed Hyperion several times but have yet to spot Mimas. Despite being more than a magnitude fainter, it lies about 240″ from the planet at maximum elongations, making it easier than Mimas, which manages just 20″. Listed below are a selection of times when these two least-often-observed moons reach great elongation.

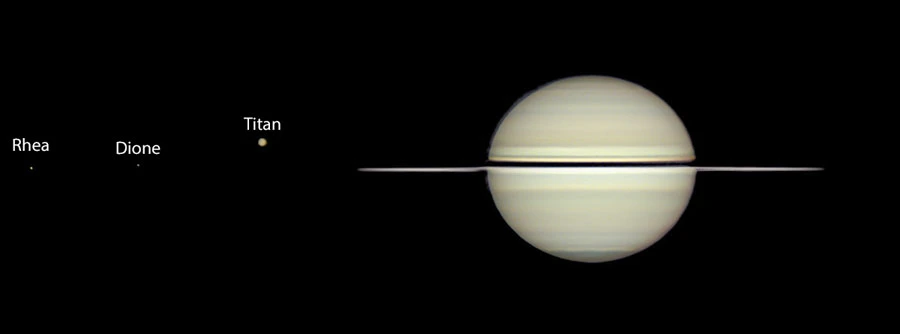

Luke Gulliver

Watching Titan shadow transits made for exciting and satisfying observing this summer and fall. While those events are now over until the next ring-plane crossing, fun with Titan isn’t. You can watch the moon itself transit Saturn’s globe. There are three remaining events for 2025. They’re best visible in the Eastern Time Zone, with two of them accessible in twilight for Midwestern observers. All times are Eastern Standard Time (EST). Data is from the Handbook of the British Astronomical Association. Be sure to use Sky & Telescope’s interactive Saturn’s Moons calculator to know which pinpoint of light is which!

Mimas at greatest eastern elongation

- November 24 at 10:48 p.m.

- December 10 at 12:42 a.m.

- December 13 at 7:12 p.m.

- December 28 at 9:12 p.m.

Hyperion at greatest elongations

- November 3 at 12:24 a.m. (western)

- December 4 at 8:24 p.m. (eastern)

- December 26 at 2:18 a.m. (eastern)

Titan moon transits

- November 22 from 1:50 to 7:51 p.m.

- December 8 from 12:38 to 6:36 p.m.

- December 24 from 11:58 a.m. to 5:42 p.m.