Trump and his cronies’ style reflects a platform where grievance is currency and performance is power.

At the events surrounding Ronald Reagan’s inauguration in 1981, guests were handed small jewelry boxes that opened with a satisfying snap. Inside, metal buttons rested on a plush blue-velvet cushion. Each bore the image of a bald eagle with its wings stretched wide before the Capitol dome, a banner streaming from its beak that read “Reagan–Bush.” The buttons were more than keepsakes; they were emblems of conservative longing. After two turbulent decades marked by civil unrest, oil shocks, the Watergate scandal, and a failed war in Vietnam, Republicans yearned to restore a pre-1960, prim and proper American society. On that day, under a clear winter sky, those gleaming buttons symbolized optimism. A card included with the gift read: “Together, let us make this A Great New Beginning.”

Republican organizers had commissioned the buttons from Ben Silver—a Charleston, South Carolina–based outfitter whose trade was, and remains, the adornment of America’s gilded class—on the assumption that every attendee of Reagan’s celebrations already owned a navy sport coat onto which the hardware could be affixed. With a swift replacement of buttons, hopsack jackets turned into blazers: not merely articles of clothing but markers of identity.

Although blazers were initially worn for sport (the term comes from the red jackets worn by members of the Lady Margaret Boat Club at St John’s College in Cambridge, which visually “blazed” along the water), by the early 1980s, they symbolized belonging in polite society. Blazers allowed one entry into country clubs and Ivy League alumni houses, where paintings of 19th-century men hanging above mahogany wainscoting enshrined success according to particular moral and professional codes. For many conservatives, such environments represented civility and decorum.

Four decades later, that uniform has all but vanished. The shift isn’t unique to Republicans—men’s fashion writ large has grown increasingly informal. But within the GOP, that broader trend reflects a reordering of power. The Republican Party is no longer governed by Reagan’s acolytes but by Donald Trump, a real estate showman whose understanding of politics is indistinguishable from his understanding of branding. Trump has remade the party not only in spirit, but also—perhaps primarily—in aesthetics, transforming it into a right-wing populist platform in which grievance is currency and performance is power. Where Reaganism once whispered the genteel respectability of brass buttons, Trumpism bellows in red MAGA hats, “Never Surrender” T-shirts, and metallic gold sneakers that give off a tinsel gleam like a casino chandelier. The shift in aesthetics mirrors that in politics: Everything is spectacle, and the louder the spectacle, the more authentic the power it claims to represent.

To trace the evolution of the Republican aesthetic, one must understand codes in men’s tailoring. Before Trump’s rise in politics, Republican dress was firmly rooted in Brooks Brothers, the oldest American menswear brand in continuous operation. The relationship between Brooks Brothers and conservatism was once so tight that the anarchic attempt by Republican operatives to stop the 2000 Florida vote recount became known as the “Brooks Brothers riot.”

For much of the 20th century, Brooks Brothers represented the white bourgeoisie—particularly WASPs who traced their roots back to the Mayflower. In the early 1900s, the company debuted its iconic No. 1 Sack Suit, which was distinguished by its soft, natural shoulders, center hook vent, and a three-button closure with lapels gently rolling to the center button. Most notably, the sack suit lacked a front dart, the long, stitched-down fold that makes the garment hug the wearer’s contours. The sack suit carried American elites from the jazz clubs of the Roaring Twenties through the Great Depression and onto the Ivy League campuses of the postwar boom.

Even so, there was a paradox stitched into the Brooks Brothers aesthetic. Because the company dressed elites, its raiments took on status as those men saw their fortunes rise with industrial capitalism. At the same time, its styles were a reflection of Yankee values that emphasized restraint and downplaying wealth. The American sack suit was more democratic than its European counterparts: straight sides, soft shoulders, and machine-finished lapels, as opposed to the shapely silhouettes in Italy and the hard, militaristic shoulders in Britain. Brooks Brothers suits were typically accompanied by matte silk, rep striped ties in dull colors, and oxford-cloth button-down shirts with frayed collars.

When Adlai Stevenson—a model of the well-bred, intellectual elite—campaigned for president in 1952, a Life photographer captured the underside of his shoe, revealing a worn-out sole. Years later, Tom Wolfe would popularize the “Boston Cracked Shoe” in The Bonfire of the Vanities, capturing this aesthetic of genteel disrepair. In this way, threadbare clothing from a certain store, worn in a particular way, could both downplay and signal affluence—the paradox of old money. Before long, this became known as Ivy Style, worn by men who rode the conveyor belt from Phillips Academy Andover to Harvard to Washington.

During the first six or so decades of the 20th century, liberals and conservatives alike wore Ivy Style into the hallowed halls of power. But as the century pushed forward, the look became politicized. After the civil rights movement, second-wave feminism, and anti-war protests, the suit went from a symbol of respectability to an emblem undeserving of awe. Young Americans refused to inherit the establishment’s uniform, adopting alternative styles: the rocker, the beatnik, the hippie, the radical.

Still, tailored clothing didn’t die. After a slow decline starting in the late 1960s, it roared back in the ’80s, this time not as the threadbare tweeds of old-money elites but as the slick uniform of a new tycoon class. This was the era of the power suit—an oversize garment with extended, padded shoulders and a severely defined waist that gave men an imposing V-shaped figure. Whereas the Brooks Brothers suit favored soft lines, this style of tailoring was angular. The power suit was worn with bright ties and banker collars, exemplified by Michael Douglas’s Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film Wall Street. If the Ivy look was about playing down wealth, the power suit announced it with exuberance.

It’s worth pausing in this era. As much as the power suit seemed like a rejection of the staid sobriety the Reaganites claimed to admire, its rise was inseparable from Reagan and his trickle-down army. Eisenhower, Nixon, and Ford had mostly accepted the New Deal’s social framework, expanding Social Security, sometimes backing public works, and maintaining a pragmatic relationship with organized labor. Reagan replaced that settlement with a brasher form of conservatism that centered market liberalization, tax cuts, and confrontation with unions. In doing so, he gave the party’s corporate elite license to pursue their old ambitions to roll back the welfare state. Reagan’s genial patriotism and Hollywood charisma repackaged these aims in a way that felt new, even as they harked back to pre–New Deal economic inequality. In a decade that worshiped millionaires and shamed the poor, the power suit became the natural uniform of a new cultural vanguard.

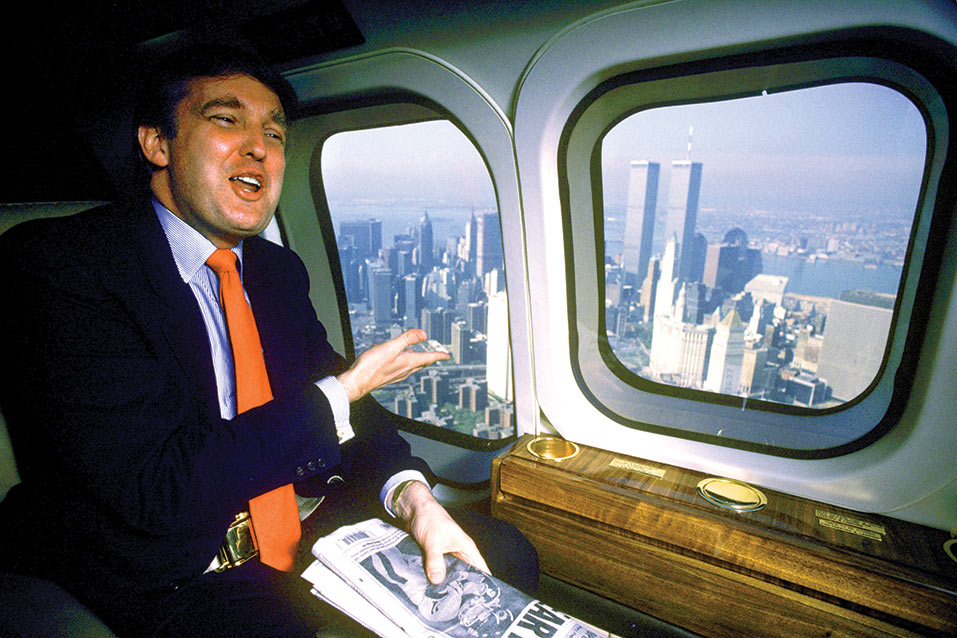

It’s no accident that this was the moment Trump burst onto the scene. With the grand opening of Trump Tower in 1983 and the publication of The Art of the Deal in 1987, he emerged as one of New York’s highest-profile figures. Like many, he played with trends in his youth like wide paisley ties and giant lapels, but he would quickly cement his image as a 1980s business magnate by adopting the power broker uniform: thick shoulder pads, satin ties in balloon colors, and outfits that echoed the American flag. Trump’s showboating style has remained there ever since.

Everything Trump wears, builds, or sells is part of that same stagecraft, all calculated to remind you that he’s rich. His Fifth Avenue penthouse is designed in an ostentatious, neo-rococo style that borrows from Louis XIV–era French opulence, which he has since imported into the Oval Office. At Mar-a-Lago, the interiors are best described as “Gilded Age fantasy meets 1980s American excess and Mediterranean pastiche.” When Trump agreed to appear on Comedy Central Roast in 2011, he told comedians that they could joke about anything—his hair, his weight, his multiple marriages, his strange comments about his daughter Ivanka—but they couldn’t question his wealth. Anthony Jeselnik later told The Hollywood Reporter, “Trump’s one rule was ‘Don’t say I have less money than I say I do.’”

The irony of a billionaire posing as a populist hasn’t gone unnoticed, but Trump’s theatrical style has helped him cast himself as an outsider. During his first term, his two biggest adversaries, Mitt Romney and Robert Mueller, embodied the polish of an older class. Both men favored soft-shouldered tailoring and conservative foulard ties, knotted in the understated four-in-hand (many people in Trump’s cabinet favor the thicker Windsor knot). Mueller was loyal to Brooks Brothers, a detail recorded by his biographer, Garrett Graff. If Romney and Mueller represented the authority of the old establishment, Trump’s square-shouldered Brioni suits mark him as a warrior against it. When he vows to “drain the swamp,” he’s talking, in part, about ridding DC of Brooks Brothers bureaucrats.

The anti-establishment image Trump has cultivated is one way he’s been able to wield power. Many people in his base have taken that aesthetic and amplified its defiance. At the center of this spectacle is the fire-red MAGA hat, which is designed not to persuade but to provoke. (Recall Marjorie Taylor Greene shouting from the stands during Biden’s 2024 State of the Union, her red hat standing out in a room full of dark suits). At rallies, supporters often show up in military gear and T-shirts featuring Trump’s mug shot, expressing how they see legal prosecution as inseparable from political persecution. A master of merchandising, Trump built a licensing empire to help bankroll his campaigns, including gold cell phones and “Never Surrender” sneakers. Representative Troy Nehls of Texas, a former sheriff aligned with the party’s populist wing, has fully embraced this chaos. Not content with the uniform of a dark worsted suit, he occasionally pairs it with a “Never Surrender” T-shirt and glossy high-tops. He also owns a collection of neckties featuring an image of Trump’s face repeated in a crude, unbroken strip, like prize tickets unfurling from a Skee-Ball machine.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

What this all adds up to is a modern Republican aesthetic, if it can be called one, that is less a coherent style than a cultural garage sale: a jumble inspired by memes and viral gimmickry. It draws not from the restrained codes of the moneyed but from the churn of pop culture and the glare of the digital age. The influence of Internet culture in politics is unmistakable—even official government accounts, such as that of the Department of Homeland Security, now post AI-generated memes designed for outrage. In place of polish and propriety, this aesthetic offers spectacle. At Trump rallies, the media personality Blake Marnell can be found in a two-piece “brick suit” with a matching tie, turning himself into a walking metaphor for the US-Mexico border wall. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth frequently appears in stars and stripes. In this context, the louder, gaudier, and more profane the display, the more it reads as authentic: Vulgarity becomes an offensive stand-in for populist credibility, a rejection of elitism, and a public performance of loyalty to Trump.

Macho grandstanding—manstanding?—plays much the same role. The GOP’s transformation from the party of country clubbers to that of the populist white working class is partially due to how much it has penetrated spaces that stoke an emergent hypermasculine culture. During his 2024 campaign, Trump engaged with manosphere podcasters like Joe Rogan, Theo Von, and Andrew Schulz. He appeared alongside UFC CEO Dana White at mixed-martial-arts events and received endorsements and messages of support from some of its top fighters. While many of these figures grew up middle-class, they’ve adopted a style of Henleys, work boots, and tactical gear. Their clothes telegraph masculine self-reliance, even if these men have never held a wrench.

The irony of the Republican rebellion against “good taste” is that it targets a ruling class that has vanished. Cultural and political power no longer reside with George Plimpton or H.W. Bush, but with tech titans like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg. Before he and Trump broke up, Musk wore “Dark MAGA” hats with black jeans and topcoats at the White House; Bezos frequently plays out an alpha male fantasy, showing up in all-black velvet suits and Ibiza-esque shirts with tight white jeans. For a man who claims that he’s fighting the “globalists,” Trump’s inauguration was conspicuously attended by Silicon Valley and Wall Street leaders.

On July 4, flanked by Republican lawmakers while the US Marine Band played patriotic marches in the background, Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act—passed by a Republican-controlled Congress. Thus far, the legislation is the crowning achievement of his second term. It folds decades of Republican ambitions into a single package, delivering roughly $5 trillion in tax cuts weighted toward the rich, pouring billions into deportations, scrapping clean energy incentives in favor of oil and gas development, and adding $150 billion to the Pentagon budget, making it one of the largest peacetime defense buildups in US history. Where Bush’s Social Security privatization plan fizzled and Paul Ryan’s austerity budgets died in committee, “BBB” has fulfilled old promises: a 12 percent cut to Medicaid over 10 years, new work requirements for SNAP, and reduced access to financial aid for low-income college students. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office projects that nearly 12 million people will lose their health insurance as a result. With Musk’s help, before the bill passed, DOGE set the foundations by dismantling foreign aid programs, including HIV/AIDS treatment and malaria surveillance in Africa.

If earlier GOP leaders failed to deliver this agenda, it was not for lack of will, but for lack of Trump’s instinct for spectacle. The old conservative uniform belonged to country clubbers who preached free trade and cast America as a beacon of liberalism. Trumpism swapped that for an anti-establishment costume, performing rebellion against a vanished class to give Republicans cover for the most plutocratic version of their agenda. He has made the GOP a more nativist party, but the core Republican priorities continue to be cutting taxes, deregulating markets, and hollowing out the administrative state.

Ten years after Trump descended his golden escalator, he has done little to restore American manufacturing or reshape foreign policy. The lives of white working-class voters haven’t improved. His populism signals revolt only through dress and demeanor, aimed not at dismantling centers of power, but at baiting members of the legacy media, academics, and coastal elites who police taste and tone. Social media companies have enabled this transformation, with algorithms rewarding the most provocative self-presentations. In an era when politics is entertainment, and power is measured in engagement metrics, the uniform does as much work as the message.

Donald Trump wants us to accept the current state of affairs without making a scene. He wants us to believe that if we resist, he will harass us, sue us, and cut funding for those we care about; he may sic ICE, the FBI, or the National Guard on us.

We’re sorry to disappoint, but the fact is this: The Nation won’t back down to an authoritarian regime. Not now, not ever.

Day after day, week after week, we will continue to publish truly independent journalism that exposes the Trump administration for what it is and develops ways to gum up its machinery of repression.

We do this through exceptional coverage of war and peace, the labor movement, the climate emergency, reproductive justice, AI, corruption, crypto, and much more.

Our award-winning writers, including Elie Mystal, Mohammed Mhawish, Chris Lehmann, Joan Walsh, John Nichols, Jeet Heer, Kate Wagner, Kaveh Akbar, John Ganz, Zephyr Teachout, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Kali Holloway, Gregg Gonsalves, Amy Littlefield, Michael T. Klare, and Dave Zirin, instigate ideas and fuel progressive movements across the country.

With no corporate interests or billionaire owners behind us, we need your help to fund this journalism. The most powerful way you can contribute is with a recurring donation that lets us know you’re behind us for the long fight ahead.

We need to add 100 new sustaining donors to The Nation this September. If you step up with a monthly contribution of $10 or more, you’ll receive a one-of-a-kind Nation pin to recognize your invaluable support for the free press.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

In “Searches”, Vauhini Vara probes the ways that we rely on the Internet and how we periodically attempt to free ourselves from its grip.

It’s a horror story about Silicon Valley, and an extreme example of what happens when we conceive of children as property.

The anonymity of the Internet makes us all vulnerable to being swindled—and it’s making us trust each other less.