Schmidt Sciences

Within three years, astronomers will have four brand-new observatories — including one in space that boasts a mirror rivaling those in the Hubble and Nancy Grace Roman space telescopes. The announcement of the ambitious Schmidt Observatory System, one of the biggest releases to come out of last week’s American Astronomical Society meeting in Phoenix, Arizona, comes courtesy of Schmidt Sciences, an initiative created and funded by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and his wife, Wendy.

The four observatories, which have already been under development for the past three to five years, were officially announced to a special-session audience with standing room only:

- The Deep Synoptic Array (DSA) has 1,650 radio dishes, each one 6.15 meters across, working in tandem on the floor of a radio-quiet valley in Nevada to take images of the radio sky.

- Similarly, the Argus Array consists of 1,212 telescopes with 11-inch apertures, which will work together to record a near-continuous movie of the visible and near-infrared sky, probably from a site in Texas.

- The Large Fiber Array Spectroscopic Telescope (LFAST) will combine 76-cm telescopes in multiples of 20 to take visible and near-infrared spectra, likely from Kitt Peak in Arizona. A prototype is in the works at Steward Observatory.

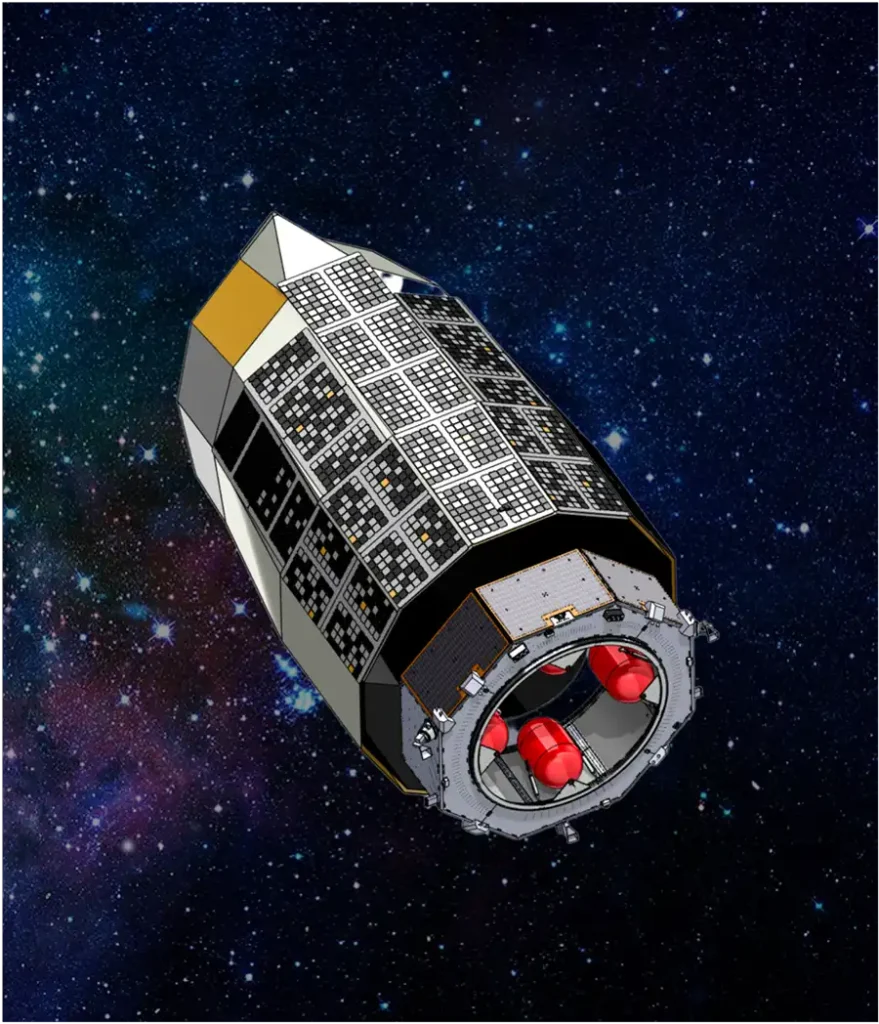

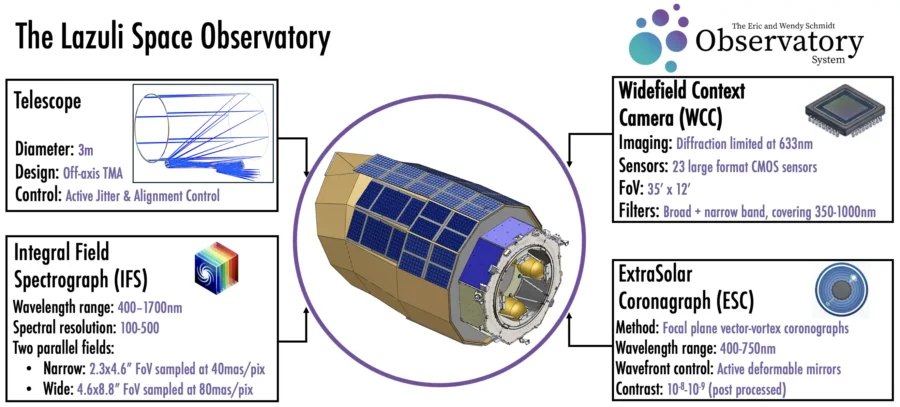

- Last but certainly not least: The Lazuli Space Telescope boasts a 3-meter mirror and will begin returning rapid-response data at visible to near-infrared wavelengths from a lunar-resonant orbit.

All four observatories are primed for some of the fastest-developing fields of astronomy, including exoplanet science and cosmology.

Schmidt Sciences is expecting to see data from all four observatories by 2029, though some are targeting earlier dates. The Argus Array team is aiming for first light as soon as 2027, and Lazuli is targeting launch in 2028. All data will be made publicly available.

The team is quick to note that these are not designed to replace flagship facilities like Hubble or Roman. At the same time, they’re not small satellites, like the privately-funded Mauve ultraviolet observatory that launched last November.

“We’re going to be very fast and risk-embracing and try to do things inexpensively, and yet try to serve world class science,” says Arpita Roy, director of astrophysics and space at Schmidt Sciences. “And we will either succeed, or we will learn something.”

Lazuli Space Observatory

Schmidt Sciences

Perhaps the most dramaatic of these projects is Lazuli. The space observatory’s 3-meter mirror is bigger than the 2.4-meter mirrors that are at the heart of the Hubble and Roman space telescopes, offering it more than half again their light-collecting power.

As crucial as the mirror’s size is the observatory’s response time, which will be at most “four hours from command to photons,” according to Roy, though they’re aiming to make it as fast as 90 minutes. That’s much faster than Hubble’s typical response time for a “target of opportunity” (such as fresh celestial explosions or a newly discovered asteroid), which typically takes days to weeks.

Among the instruments aboard Lazuli is a camera with 23 CMOS detectors, each of which will be outfitted with fixed filters (both broadband and narrowband) covering wavelengths spanning the visible to near-infrared range (400 to 1,700 nanometers). The observatory will also have an integral field spectrograph, which takes spectra across an entire image as well as a coronagraph, a mask that blocks bright sources to enable detection of fainter ones. Supriya Chakrabarti (University of Massachusetts, Lowell), whose team has contributed to Lazuli, is excited to use that capability to directly image exoplanets around nearby stars.

Lazuli is not a Hubble replacement. But it does offer competitive advantages, drawing on technology that is 20 years more advanced than what is onboard the iconic observatory.

Schmidt Sciences

The observatory also has advantages compared to Roman: Its off-axis mirror secondary, for example, makes coronagraph construction much simpler, because the secondary mirror doesn’t block the primary’s view, says Ewan Douglas (University of Arizona), who’s leading Lazuli’s coronagraph development. That means that Lazuli’s instrument will be much simpler and the data therefore easier to analyze than the one soon to fly with the Roman space telescope. (Douglas was also on the team that developed Roman’s coronagraph.) Both instruments offer value to astronomers, because, unlike Roman, Lazuli’s coronagraph won’t offer spectroscopy.

Most ambitious of all is the observatory’s timeline. Though the concept has been in development for a few years, two years to launch is admittedly aggressive, the Lazuli team notes. But it’s necessary to work together with other observatories. “We’re targeting to launch in July of 2028,” noted Pete Klupar, Lazuli’s executive director. “We chose that date not because it was hard . . . [but] so that we would be coordinated with Roman and [the Vera C.] Rubin [Observatory]. . . . That’s what’s holding our feet to the fire.”

From the Ground

Caltech / IPAC / DSA

The other three facilities in the Schmidt Observatory System are all ground arrays, combining the power of multiple, smaller telescopes in unprecedented ways.

The Deep Synoptic Array, which Sky & Telescope previewed in the September 2023 issue, has been in the works for some time. Precursors named DSA-10 and DSA-110, both funded by the National Science Foundation, combined smaller numbers of dishes. Combining data from larger numbers of dishes has remained a challenge, though, one that principal investigator Greg Hallinan (Caltech) says wasn’t solved for a few years.

When radio dishes work together, a process known as radio interferometry, it takes a lot of computational work to wrangle a radio image from those data. So, with the DSA prototypes, the team focused on science that didn’t require imaging.

But in 2018, they made a breakthrough. “We realized that if we pushed [the array] to thousands of antennas . . . suddenly it meant you could build a system that made images in real time for the first time,” Hallinan says. All those dishes collect a ridiculous amount of data — at the rate of about a zettabyte per year, it’s equivalent to the world’s streaming of Netflix. Yet those data don’t need to be stored long-term. DSA’s radio camera will create science-ready radio images, only holding on to raw data for an additional week or so.

DSA is complementary to existing radio arrays, which cover a hundredfold wider frequency range at sharper resolution. The array captures details 3 arcseconds across, which is fuzzy even compared to the ageing Very Large Array, which resolves down to tenths of an arcsecond. But DSA’s field of view is comparatively large, and the trade-off is volume: “Every radio telescope ever built has detected about 10 million radio sources,” Hallinan says. “We double that in the first 24 hours and . . . we’ll detect about a billion radio sources over a five-year survey.”

Those sources will include about 200 millisecond pulsars. Only a few dozen of these rapidly spinning neutron stars are known now, and discovering hundreds more will help astronomers detect the gravitational waves coming from the collisions of supermassive black holes. The survey will also map cosmic hydrogen, shedding light on dark matter, as well as black hole and star formation activity across the universe.

Read more about the Deep Synoptic Array in a preview by Sky & Telescope Contributing Editor Govert Schilling in the September 2023 issue.

Schmidt Sciences

At visible wavelengths, the Argus Array (named for the hundred-eyed Argus Panoptes of Greek mythology) will set 1,212 telescopes in tilted, circular arrangements to capture 8,000 square degrees of sky every minute. That’s about the field of view of the human eye, says project lead Nick Law (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

The 11-inch telescopes come from Observable Space, a company that offers both PlaneWave Instruments and OurSky software. (Those 11-inch astrographs will soon be available for amateur astronomers to purchase, too.)

The Argus Array will capture an unprecedentedly fast movie of the night sky, with an aperture equivalent to an 8-meter telescope. Compare that to the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, which just came online last year: Rubin’s also capturing a celestial movie, but it takes three days to cover the whole night sky. The trade-off here is sensitivity: In a single take, Rubin’s images go much deeper.

Roy notes that the two are complementary: “[Argus] is like the action movie to Rubin’s high drama of the sky.”

See our upcoming feature on compound telescopes in the May 2026 issue of Sky & Telescope — subscribe today!

While Argus won’t reach Rubin-level depth, the team does plan to add together the multitude of images that the telescope collects minute to minute, at a rate of at least 130 terabytes per night. The more images that are added together, the deeper the observations will go. (Like the DSA, all that raw data will not be stored long-term.) The resulting combination of field of view and depth is unique — as Law puts it, “Argus sits in a new regime.”

Schmidt Sciences / Chris Gunn

Accompanying Argus’s visible-to-near-infrared imaging are spectra across the same wavelength range from the Large Fiber Array Spectroscopic Telescope. A single unit of LFAST will consist of 20 small telescopes on a common alt-az mount, equivalent to a 3.5-meter telescope. Combining 10 of these units results in the equivalent light-collecting power of a 10-meter telescope.

Each one of these units will be outfitted with multiple spectrographs, helping to characterize atmospheres on rocky planets around nearby stars, rapidly follow up on supernovae, and all sorts of science in-between. A prototype is targeted for completion by the end of the year, says project lead Chad Bender (University of Arizona).

The Road Ahead

Schmidt Sciences’ announcement fits into a historical pattern of philanthropy-funded astronomy, which has historically included the Lick, Lowell, Yerkes, and Palomar observatories. While philanthropy died back with the dawn of the Space Age, both spaceflight and hardware development costs have come down enough that private donors are making a comeback, with notable examples including the Breakthrough Initiative and the Simons Foundation.

Yet, while philanthropy may be ticking up, Schmidt Sciences has no intention of replacing federal funding, which is still needed to fund general science.

There’s also the issue of longevity. There are no funds as yet for a legacy archive, and the lifetimes of the observatories are purposefully limited. “Part of our philosophy is that we don’t want to operate things for decades and decades,” Roy said at the conference. Schmidt Sciences is committing to three to five years of operations for each telescope. But she added, “If things keep working, we’ll keep operating it.”

The observatory teams also have great challenges ahead of them, not all of which are yet solved. The extraordinary amount of data, even if not all of it is stored forever, is going to be difficult to manage, analyze, and provide in science-ready formats for the greater astronomical community. AI will have a role to play in tackling those challenges.

But people power matters. To that end, Schmidt Sciences announced up to five First Light Awards: Each one goes to an early-career astronomer (that is, a professional astronomer without tenure), who will receive $500,000 per year for up to five years to support a team through the expected lifetime of any one of these observatories.

The crowd in the packed conference room was paying attention: Dozens of smartphones flew up during that part of the announcement, snapping pictures of the award information. Within a week, Roy says, more than 100 people had already signed up to learn more.

Toward the end of the announcement, when asked how Schmidt Sciences would measure success, President Stuart Feldman joked, “Nobel Prizes per year.” Continuing more seriously, he nevertheless emphasized high expectations: “Weighing kilograms of papers or kilobytes of archive is simply not the right measure. Exciting outcomes that would have been unlikely to have arisen without our resources is really the answer.”

“I’m so excited about the whole thing,” Roy adds, speaking on a personal level. “It makes me think of when I watch my kids play with Play-Doh — I have all this raw potential that I get to shape and put back into astronomy.”