Tech Stack and Tools

Flim was built in Webflow. We made good use of the built-in functionality and added a few JavaScript libraries on top to help things go smoothly.

As always, we used GSAP for our animations. The new GSAP interactions built into Webflow weren’t available at the time we started working on this, so our interactions are built using custom code, which works really well too.

We also used Lenis for smooth scrolling, Lottie for the baked animations, and Rapier for physics.

Transitions

We wanted a quick, clean, mask animation for our page transitions. To do so, we created two simple GSAP timelines.

The first one hides the page with a repeating pattern. It plays whenever we click on an internal link, before navigating to the page.

const hideTl = gsap.timeline();

hideTl.set(loaderElem, { visibility: 'visible' });

hideTl.fromTo(maskElem, {

'--maskY': '0%',

}, {

'--maskY': '100%',

duration: 0.5,

ease: 'power2.inOut',

onComplete: () => {

window.location = destination;

}

});The other one shows the page again, playing when the page loads.

const showTl = gsap.timeline();

showTl.addLabel('start', 0.5);

showTl.fromTo(maskElem, {

'--maskY': '100%',

}, {

'--maskY': '200%',

duration: 0.5,

ease: 'power2.inOut',

}, 'start')

.set(loaderElem, {

visibility: 'hidden'

});And for the home page, we have a custom animation added, where the logo animates in with the transition. We created another timeline that plays at the same time as the transition mask. We can add the new home timeline to the timeline we already created, using the start label we set up.

const homeTl = gsap.timeline();

// …

showTl.add(homeTl, 'start');Text Animations

Like we often do, we wanted the page’s text to appear when it comes into view. Here, we wanted each line to be staggered when they appeared. To do so, we use a combination of GSAP’s SplitText and ScrollTrigger.

We first targeted every text container that needed the build-on animation. Here, we targeted specific classes, but we could also target every element that has a specific attribute.

We first create a timeline that starts when the element comes into view with ScrollTrigger.

Then we create a SplitText instance, and on split, we add a tween animating each line sliding up with a stagger. We also store that tween to be able to revert it if the text is split again.

const tl = gsap.timeline({

paused: true,

scrollTrigger: {

trigger: el,

start: 'top 90%',

end: 'top 10%',

once: true

}

});

let anim;

SplitText.create(el, {

type: 'lines',

autoSplit: true,

mask: 'lines',

onSplit(self) {

if (anim) anim.revert();

anim = gsap.fromTo(self.lines, {

yPercent: 100,

}, {

yPercent: 0,

duration: 0.8,

stagger: 0.1,

ease: 'power3.inOut',

});

tl.add(anim, 0);

}

});We also have a fun animation on the button’s hover. Here, we use GSAP’s SplitText with characters, and animate the opacity of those characters on mouse hover. We target the containers and the text elements within, with the data attribute data-hover’s value.

const hoverElems = document.querySelectorAll('[data-hover="container"]');

hoverElems.forEach(elem => {

const textElem = elem.querySelector('[data-hover="text"]');

// animation

let tl;

SplitText.create(el, {

type: 'chars',

onSplit(self) {

if (tl) tl.revert();

tl = gsap.timeline({ paused: true });

tl.to(self.chars, {

duration: 0.1,

autoAlpha: 0,

stagger: { amount: 0.2 },

});

tl.to(self.chars, {

duration: 0.1,

autoAlpha: 1,

stagger: { amount: 0.2 },

}, 0.3);

}

});

// events

const handleMouseEnter = () => {

if (!tl || tl.isActive()) return;

tl.play(0);

}

elem.addEventListener('mouseenter', handleMouseEnter);

});Lotties

Lotties can be easily integrated with Webflow’s Lottie component. For this project though, we opted to add our Lotties manually with custom code, to have full control over their loading and playback.

Most of the lottie animations load a different lottie, and change between the versions depending on the screen size.

Then, the main challenge was playing the beginning of the animation when the element came into view, and playing the end of the animation when we scroll past it. For some sections, we also had to wait for the previous element’s animation to be over to start the next one.

Let’s use the title sections as an example. These sections have one lottie that animates in when the section comes into view, and animates out when we scroll past it. We use two ScrollTriggers to handle the playback. The first scroll trigger handles playing the lottie up until a specific frame when we enter the area, and playing the rest of the lottie when we leave. Then, the second ScrollTrigger handles resetting the lottie back to the start when the section is entirely out of view. This is important to avoid seeing empty sections when you go back to sections that have already played.

let hasEnterPlayed, hasLeftPlayed = false;

// get total frames from animation data

const totalFrames = animation.animationData.op;

// get where the animation should stop after entering

// (either from a data attribute or the default value)

const frameStopPercent = parseFloat(

section.getAttribute('data-lottie-stop-percent') ?? 0.5

);

// get the specific frame where the animation should stop

const frameStop = Math.round(totalFrames * frameStopPercent);

// scroll triggers

ScrollTrigger.create({

trigger: section,

start: 'top 70%',

end: 'bottom 90%',

onEnter: () => {

// do not play the enter animation if it has already played

if (hasEnterPlayed) return;

// play lottie segment, stopping at a specific frame

animation.playSegments([0, frameStop], true);

// update hasEnterPlayed flag

hasEnterPlayed = true;

},

onLeave: () => {

// do not play the leave animation if it has already played

if (hasLeftPlayed) return;

// play lottie segment, starting at a specific frame

// here, we do not force the segment to play immediately

// because we want to wait for the enter segment to finish playing

animation.playSegments([frameStop, totalFrames]);

// update hasLeftPlayed flag

hasLeftPlayed = true;

},

onEnterBack: () => {

// do not play the leave animation if it has already played

if (hasLeftPlayed) return;

// play lottie segment, starting at a specific frame

// here, we do force the segment to play immediately

animation.playSegments([frameStop, totalFrames], true);

// update hasLeftPlayed flag

hasLeftPlayed = true;

},

});

ScrollTrigger.create({

trigger: section,

start: 'top bottom',

end: 'bottom top',

onLeave: () => {

// on leave, we want the lottie to already have entered when we scroll

// back to the section

// update the state flags for entering and leaving animations

hasEnterPlayed = true;

hasLeftPlayed = false;

// update lottie segments for future play, here it starts at the end

// of the enter animation

animation.playSegments(

[Math.min(frameStop, totalFrames - 1), totalFrames], true

);

// update lottie playback position to start and stop lottie

animation.goToAndStop(0);

},

onLeaveBack: () => {

// on leave back, we want the lottie to be reset to the start

// update the state flags for entering and leaving animations

hasEnterPlayed = false;

hasLeftPlayed = false;

// update lottie segments for future play, here it starts at the

// start of the enter animation

animation.playSegments([0, totalFrames], true);

// update lottie playback position to start and stop lottie

animation.goToAndStop(0);

},

});Eyes

The eyes dotted around the site were always going to need some character, so we opted for a cursor follow combined with some increasingly upset reactions to being poked.

After (quite a lot) of variable setup, including constraints for the movements within the eyes, limits for how close the cursor should be to an eye for it to follow, and various other randomly assigned values to add variety to each eye, we are ready to start animating.

First, we track the mouse position and update values for the iris position, scale and whether it should follow the cursor. We use a GSAP utility to clamp some values between -1 and 1.

// Constraint Utility

const clampConstraints = gsap.utils.clamp(-1, 1);

// Track Mouse

const trackMouse = (e) => {

// update eye positions if area is dynamic

if (isDynamic) {

updateEyePositions();

}

mousePos.x = e.clientX;

mousePos.y = e.clientY - area.getBoundingClientRect().top;

// update eye variables

for (let x = 0; x < eyes.length; x++) {

let xOffset = mousePos.x - eyePositions[x].x,

yOffset = mousePos.y - eyePositions[x].y;

let xClamped = clampConstraints(xOffset / movementCaps.x),

yClamped = clampConstraints(yOffset / movementCaps.y);

irisPositions[x].x = xClamped * pupilConstraint.x;

irisPositions[x].y = yClamped * pupilConstraint.y;

irisPositions[x].scale = 1 - 0.15 *

Math.max(Math.abs(xClamped), Math.abs(yClamped));

if (

Math.abs(xOffset) > trackingConstraint.x ||

Math.abs(yOffset) > trackingConstraint.x

) {

irisPositions[x].track = false;

} else {

irisPositions[x].track = true;

};

};

};

area.addEventListener('mousemove', trackMouse);We then animate the eyes to those values in a requestAnimationFrame loop. Creating a new GSAP tween on every frame here is probably overkill, especially when things like quickTo exist, however this allows us to maintain variation between the eyes, and we are rarely tracking more than a couple at a time, so it’s worth it.

const animate = () => {

animateRaf = window.requestAnimationFrame(animate);

for (let x = 0; x < eyes.length; x++) {

// if track is false don't bother

if (!irisPositions[x].track) continue;

// if this eye was in the middle of an ambient tween kill it first

if (eyeTweens[x]) eyeTweens[x].kill();

// irides are the plural of iris

gsap.to(irides[x], {

duration: eyeSpeeds[x],

xPercent: irisPositions[x].x,

yPercent: irisPositions[x].y,

scale: irisPositions[x].scale

});

};

};

let animateRaf = window.requestAnimationFrame(animate);Next we have a function that runs every 2.5 seconds, which randomly applies some ambient movements. This creates a bit more character and even more variety, as the look direction, rotation, and the delay, are all random.

const animateBoredEyes = () => {

for (let x = 0; x < eyes.length; x++) {

// skip eyes that are tracking the cursor

if (irisPositions[x].track) continue;

// if this eye was in the middle of an ambient tween kill it first

if (eyeTweens[x]) eyeTweens[x].kill();

// get a random position for the pupil to move to and the matching scale

const randomPos = randomPupilPosition();

// maybe do a big spin

if (Math.random() > 0.8) gsap.to(inners[x], {

duration: eyeSpeeds[x],

rotationZ: '+=360',

delay: Math.random() * 2

});

// apply the random animation

eyeTweens[x] = gsap.to(irides[x], {

duration: eyeSpeeds[x],

xPercent: randomPos.x,

yPercent: randomPos.y,

scale: randomPos.scale,

delay: Math.random() * 2

});

};

};

// Ambient movement

animateBoredEyes();

let boredInterval = setInterval(animateBoredEyes, 2500);Finally, when the user clicks an eye we want it to blink. We also want it to get angrier if the same eye is picked on multiple times. We use a combination of GSAP to apply the clip-path tween, and CSS class changes for other various style changes.

// Blinks

const blinks = [];

const blinkRandomEye = () => {

// select a random eye and play its blink at normal speed

const randomEye = Math.floor(Math.random() * eyes.length);

blinks[randomEye].timeScale(1).play(0);

};

const blinkSpecificEye = (x) => {

blinkInterval && clearInterval(blinkInterval);

// set which class will be applied based on previous clicks of this eye

const clickedClass =

eyeClicks[x] > 8 ? 'furious' : eyeClicks[x] > 4 ? 'angry' : 'shocked';

// the time until this eye is re-clickable increases as it gets angrier

const clickedTimeout =

eyeClicks[x] > 8 ? 3000 : eyeClicks[x] > 4 ? 2000 : 500;

// increase the click count

eyeClicks[x]++;

// apply the new class

eyes[x].classList.add(clickedClass);

// quick agitated blink

blinks[x].timeScale(3).play(0);

// reset after cooldown

setTimeout(() => {

eyes[x].classList.remove(clickedClass);

blinkInterval = setInterval(blinkRandomEye, 5000);

}, clickedTimeout);

}

const setupBlinks = () => {

// loop through each eye and create a blink timeline

for (let x = 0; x < eyes.length; x++) {

const tl = gsap.timeline({

defaults: {

duration: .5

},

paused: true

});

tl.to(innerScales[x], {

clipPath: `ellipse(3.25rem 0rem at 50% 50%)`

});

tl.to(innerScales[x], {

clipPath: `ellipse(3.25rem 3.25rem at 50% 50%)`

});

// store the blinks so that the random blink

// and specific eye blink functions can use them

blinks.push(tl);

// blink when clicked

eyes[x].addEventListener('click', () => blinkSpecificEye(x));

};

};

setupBlinks();

blinkRandomEye();

let blinkInterval = setInterval(blinkRandomEye, 5000);Here is a Codepen link showing an early demo of the eyes created during concepting. The eyes on the live site get angrier, though.

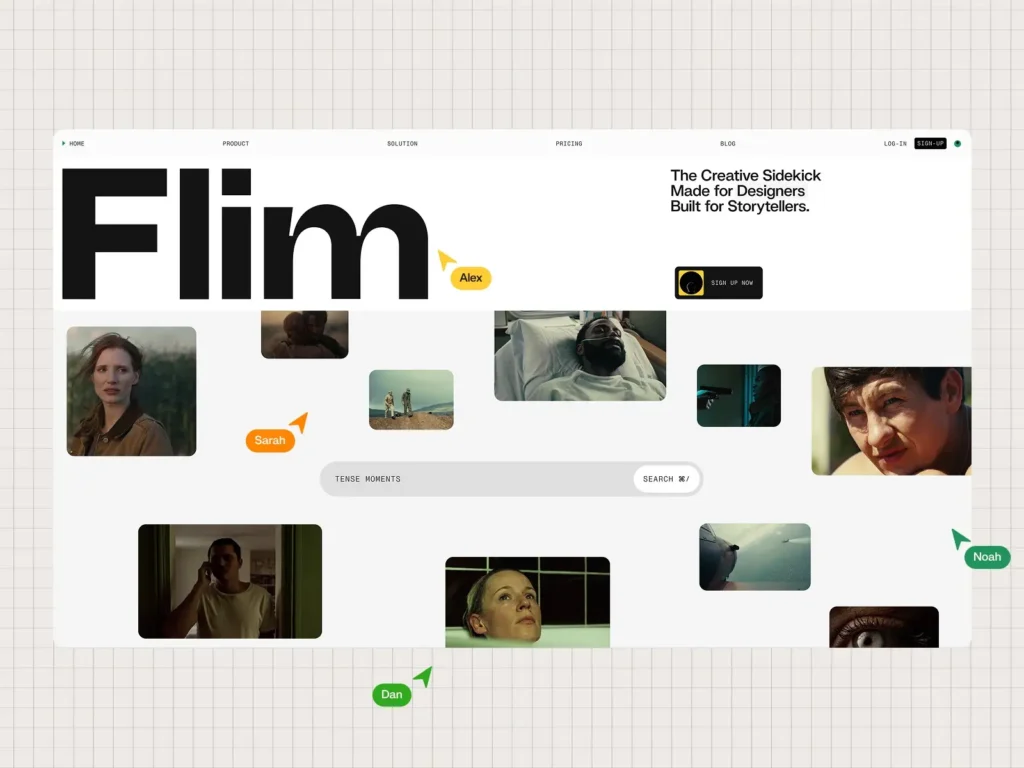

Hero Animation

The home hero features a looping timeline which shows various samples of imagery to match a pre-set search term in the search bar. Additionally, the timeline needed to be interruptible, hiding the images when the user clicks to type their own search term and continuing if the search bar is focused out with no input.

The GSAP timeline code itself here is quite simple, but one thing to note is that we decided to have the timeline of images being revealed and then hidden be recreated each time on a setInterval, rather than having one master timeline which controls the entire sequence. This made things simpler when we needed to interrupt the images and hide them quickly as it allows us to avoid having a master timeline competing with an interrupt timeline or tween applying updates to the same elements.

const imageGroupCount = imageGroups.length;

const nextImages = () => {

if (imageTl) imageTl.kill();

if (clearTl) clearTl.kill();

imageTl = gsap.timeline({

defaults: {

duration: .7,

stagger: function (index, target, list) {

return index === 0 ? 0 : Math.floor(index / 3.01) * 0.3 + .3;

}

}

});

…

prevIndex = nextIndex;

nextIndex = (nextIndex + 1) % imageGroupCount

};

const hideImages = () => {

if (imageTl) imageTl.kill();

if (clearTl) clearTl.kill();

clearTl = gsap.timeline({

defaults: {

duration: .7

}

});

…

};Brand Carousel

The brand carousel has a simple marquee animation that was set up with a looping GSAP timeline.

First, we clone the inner element to allow us to have a seamless loop.

const cloneElem = innerElem.cloneNode(true);

wrapperElem.appendChild(cloneElem);Here, we only cloned it once because the inner element is large enough to assume one clone will cover the screen no matter the screen size. Otherwise, we would have to calculate how many clones we need for the screen to be filled when the first element has been translated entirely to its full width.

Then we set up a looping timeline, where we translate both the inner element and its clone, 100% to their left. The duration can be changed for different speeds, it can even be dynamic depending on the number of elements inside our marquee.

const loopTl = gsap.timeline({ repeat: -1, paused: true });

loopTl.fromTo([innerElem, cloneElem], {

xPercent: 0,

}, {

xPercent: -100,

duration: 10,

ease: 'linear'

});Finally, we play and pause the timeline depending on if the section is in view, using ScrollTrigger.

const scrollTrigger = ScrollTrigger.create({

trigger: wrapperElem,

start: 'top bottom',

end: 'bottom top',

onToggle: (self) => {

if (self.isActive) {

loopTl.play();

} else {

loopTl.pause();

}

}

});What is Flim Section

The next section, introducing Flim, had a variety of interactions we needed to create.

First, the images needed to appear over some text, and then go to their specific position inside of a recreation of a Flim interface. This can be a tricky thing to accomplish while keeping things responsive. A good solution for this kind of animation is to use GSAP’s Flip.

Here, we have the images styled within the first container, and style them differently in the second container. We then add a ScrollTrigger to the text element, and when it comes into the center of the screen, we use Flip to save the state, move the images from their initial container, to the second container, and animate the change of state.

ScrollTrigger.create({

trigger: textElem,

start: 'center center',

end: 'top 10%',

onEnter: () => {

const state = Flip.getState(images);

interfaceWrapper.append(...images);

Flip.from(state, {

duration: 1,

ease: 'power2.inOut',

});

}

});The other portion of this section has falling shapes, which we’ll talk about soon, that fall into an element that scrolls horizontally. To trigger this animation we used ScrollTrigger, as well as matchMedia, to keep the regular scroll on mobile.

On desktop breakpoints we create a tween on a slider element that translates it 100% of its width to its left. We add a scroll trigger to that tween, that scrubs the animation and pins the wrapper into place for the duration of this animation.

const mm = gsap.matchMedia();

mm.add('(min-width:992px)', () => {

gsap.to(sliderElem, {

xPercent: -100,

ease: 'power2.inOut',

scrollTrigger: {

trigger: triggerElem,

start: 'top top',

end: 'bottom bottom',

pin: wrapperElem,

scrub: 1,

}

});

});Physics

A big challenge for us was the physics sections, which are featured both on the home page and the 404 page. We can think of these sections as being built twice: we have the actual rendered scene, with DOM elements, and the physics scene, which is not rendered and only handles the way the elements should move.

The rendered scene is quite simple. Each shape is added within a container, and is styled like any other Webflow element. Depending on the shape, it can be a simple div that is styled, or an SVG. We add some useful information to data attributes like the type of shape it is, to be able to use that when setting up the physics scene.

For the physics side, we first create a Rapier world with gravity.

const world = new RAPIER.World({ x: 0, y: -9.81 });Then, we go through each shape within the container, and set up their physics counterpart. We create a rigidBody, and place it where we want the shape to start. We then create a collider that matches the shape. Rapier provides some colliders for common shapes like circles (ball), rectangles (cuboid) or pills (capsule). For other shapes like the triangle, hexagon and numbers, we had to create custom colliders with Rapier’s convexHull colliders.

We use the DOM element’s size to set up the colliders to match the actual shape.

Here’s an example for a square:

const setupSquare = (startPosition, domElem) => {

const rigidBodyDesc = RAPIER.RigidBodyDesc.dynamic();

const rigidBody = world.createRigidBody(rigidBodyDesc);

const x = startPosition.x * containerWidth / SIZE_RATIO;

const width = domElem.clientWidth * 0.5 / SIZE_RATIO;

const height = domElem.clientHeight * 0.5 / SIZE_RATIO;

const y = startPosition.y * containerHeight / SIZE_RATIO + height;

const colliderDesc = RAPIER.ColliderDesc.cuboid(width, height);

const collider = world.createCollider(colliderDesc, rigidBody);

return rigidBody;

}Here, startPosition is the world position we want the shape to start at, containerWidth & containerHeight are the container DOM element’s size and domElem is the shape’s DOM element. Finally, SIZE_RATIO is a constant (in our case, equal to 80) that allows us to convert pixel sizes to physics world sizes. You can try out different values and see how this is useful, but basically, if the elements are really big in the physics world, they will be very heavy and fall very fast.

Now we just create some rigid bodies and colliders for the ground and the walls, so that our shapes can avoid just falling forever. We can use the container DOM element’s size to properly size our ground and walls.

Setting up the ground:

const groundRigidBodyType = RAPIER.RigidBodyDesc.fixed()

.setTranslation(0, -0.1);

const ground = world.createRigidBody(groundRigidBodyType);

const groundColliderType = RAPIER.ColliderDesc.cuboid(

containerWidth * 0.5 / SIZE_RATIO, 0.1

);

world.createCollider(groundColliderType, ground);Now that everything is set up, we need to actually update the physics on every frame for things to start moving. We can call requestAnimationFrame, and call Rapier’s world’s step function, to update the physics world on each frame.

Our actual rendered scene doesn’t move yet though. Like we said, these are two different scenes, so we need to make the rendered scene move like the physics one does. On each frame, we need to go through each shape. For each shape, we get the rigidBody’s translation and rotation, and we can use CSS transform to move and rotate the DOM element to match the physics element.

let frameID = null;

const updateShape = (rigidBody, domElem) => {

// get position & rotation

const position = rigidBody.translation();

const rotation = rigidBody.rotation();

// update DOM element’s transform

domElem.style.transform =

`translate(-50%, 50%) translate3d(

${position.x * SIZE_RATIO}px,

${(-position.y) * SIZE_RATIO}px,

0

) rotate(${-rotation}rad)`;

}

const update = () => {

// update world

world.step();

// update shape transform

updateShape(shapeRigidBody, shapeDomElem);

// request next frame

frameID = requestAnimationFrame(update);

}We now need to make it so that the elements start falling when the section comes into view, or else we’ll miss our nice falling animation. We also don’t want our physics simulation to keep running for no reason when we can’t actually see the section. This is when we use GSAP’s ScrollTrigger, and set up a trigger on the section. When we enter the section, we start the requestAnimationFrame loop and when we leave the section, we stop it.

const start = () => {

// start frame loop

frameID = requestAnimationFrame(update);

}

const stop = () => {

cancelAnimationFrame(frameID);

frameID = null;

}

ScrollTrigger.create({

trigger: '#intro-physics-container',

endTrigger: '#intro-section',

start: 'top-=20% bottom',

end: 'bottom top',

onEnter: () => {

start();

},

onEnterBack: () => {

start();

},

onLeave: () => {

stop();

},

onLeaveBack: () => {

stop();

},

});One last thing to keep in mind, is that we use the DOM element’s size to create all of our colliders. That means we actually have to clean up everything and create our colliders again on resize, or our physics scene will not match our rendered scene anymore.

Footer

A fun little animation we like in this project is the dot of the “i” in the logo revealing a video like a door.

It is actually quite simple to do using ScrollTrigger. With door being our black square element, and video being the video hidden behind it, we can set up an animation on the door element’s rotation, and create a scroll trigger to scrub it with the scroll when it comes into view.

gsap.to(door, {

rotationY: 125,

scrollTrigger: {

trigger: door,

start: 'top 90%',

end: 'max',

scrub: true,

},

onStart: () => {

video.play();

}

});The ScrollTrigger’s end value is set to max because these elements are inside the footer, so we want the animation to end when the user reaches the bottom of the page.

The door element needs to have a transform perspective set up for the rotation to appear to be 3D. We also only start playing the video when the animation starts, because it isn’t visible before that anyway.

Conclusion

Flim was really interesting and brought a lot of challenges. From multiple Lotties guiding the user throughout the page, to physics on some 2D elements, there was a lot to work on! Using GSAP and Webflow was a solid pairing even before the new GSAP features were added, so we look forward to giving those a try in the near future.

C’était un super projet et on est très contents du résultat 🙂 🇫🇷

Our Stack

- Webflow

- GSAP for animation

- Lenis for scroll

- Lottie for After Effects animation

- Rapier for physics