Bob King

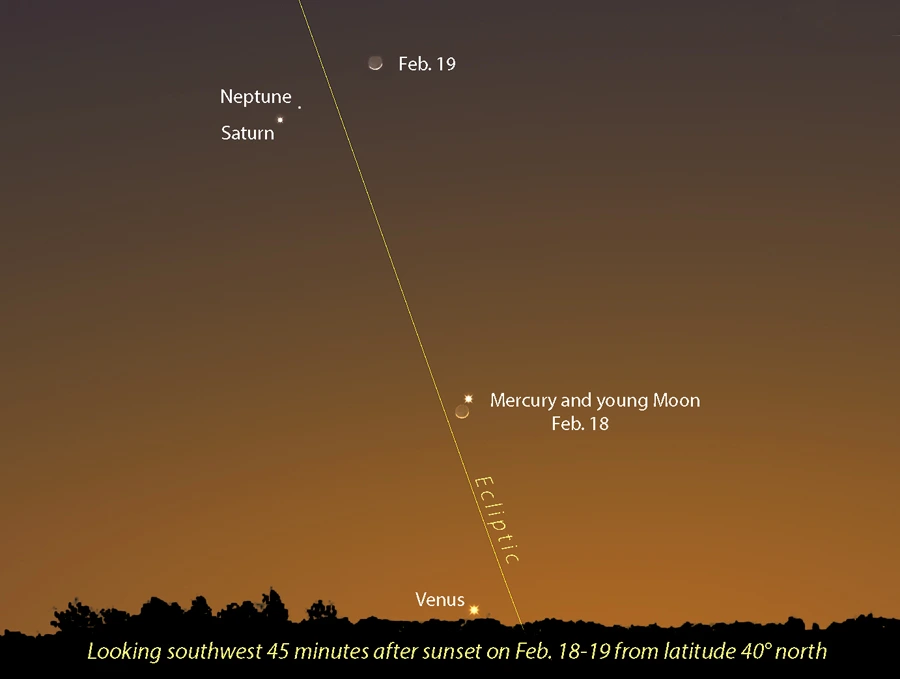

Well before the official start of spring, skywatchers divine the season’s arrival in the slant of the crescent Moon at dusk. From fall through early winter, the young Moon keeps low in the southern sky, where bright twilight makes a day-old crescent difficult if not impossible for Northern Hemisphere observers to see. But by February, its angle to the western horizon steepens considerably. Just a day after the new Moon, the fragile crescent pole vaults almost directly above the Sun into a dark sky.

Crescent hunters look forward to spring evenings to catch the slenderest crescents possible. Old and young Moons are among the most viscerally fragile sights in the night sky. When paired with a bright planet, the spectacle can move us even more.

The evening of Wednesday, February 18th, will present just such an opportunity. The 1.5-day-old lunar crescent, just 2.4% illuminated and thinner than a bread crust, will float low in the west-southwest sky from a half-hour after sunset dusk until twilight’s end. As the sky darkens, you’ll see the Moon filled with translucent Earthshine, a sight well worth observing in binoculars. You might be surprised how many lunar seas and major craters are visible in the blue-gray light reflected off of our home planet.

A celestial traffic jam

Stellarium with additions by Bob King

Wonderful as that will be, it’s only the half of it. The Moon also will be in close conjunction with the planet Mercury, which shines at magnitude –0.6, nearly as bright as Canopus. From the U.S., at middle latitudes, the Earth-lit limb will pass only about 10′ (one-third of the Moon’s apparent diameter) south of the planet around 6:30–7 p.m. Central Standard Time. A small telescope will show Mercury’s 53% waning gibbous phase — two “moons” for the price of one.

Stellarium

Since the planet will be just 7″ across, use a magnification around 100× for a clear view. Their close pairing also presents an opportunity to compare their albedos. Both are covered in dark soil and are similarly reflective — Mercury returns only about 9% of the light it receives from the Sun; the Moon reflects 12%. Can you discern a difference?

Observers in the Eastern and Central Time Zones will see the Moon continue to approach Mercury as the pair slowly sinks to the western horizon. By the time it’s twilight in the mountain states and West Coast, the crescent and Mercury will still be snug but parting.

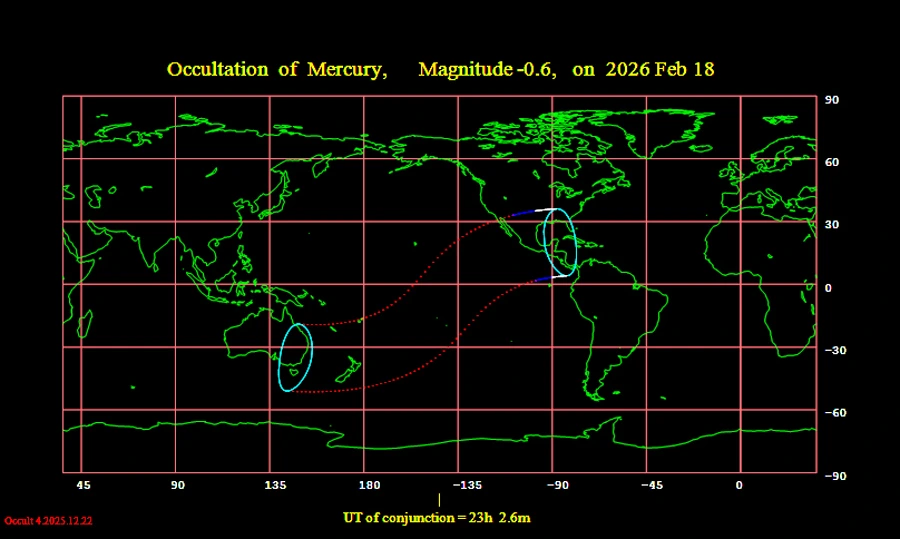

Occult 4

Count yourself lucky if you live in the southern U.S., from western Florida through far southern Arizona. You’ll see the dark lunar limb occult the planet. From locations farther west — across the South Pacific Ocean all the way to New Zealand and western Australia — the occultation occurs in daylight.

Drop by the International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA)’s website for details, where you’ll find a list of cities, along with times of Mercury’s disappearance and reappearance. Note that the times are UT or Universal Time. Subtract five hours to convert to EST, six for CST, seven for MST, and eight for PST.

Stellarium

There’s more, though you’ll need optical aid to see it. The following evening, February 19th, the Moon will be in conjunction with Saturn and Neptune. Coincidentally, the two outer planets recently completed their final in a series of three consecutive conjunctions, so they’re still close — just 49′ apart — and located about 4° south of the thickening crescent. And don’t forget Mercury! It will still be in the mix a dozen degrees below the Moon.

To make sure you enjoy both events to the max, find a location with an unobstructed western horizon and start early — 20 minutes to a half-hour after sunset — and use binoculars. That way you’ll also get a shot a seeing Venus, located about 7° (a little more than one binocular field) almost directly below Mercury. Since knowing the time of sunset is important, use this sunset calculator to find out when the Sun exits the stage.

I’ll be out there watching with you — weather permitting, of course!