In this tutorial, we’ll explore how to use Three.js and shaders to take a regular video, pixelate the 2D feed, and extrude those results into 3D voxels, finally controlling them with the Rapier physics engine.

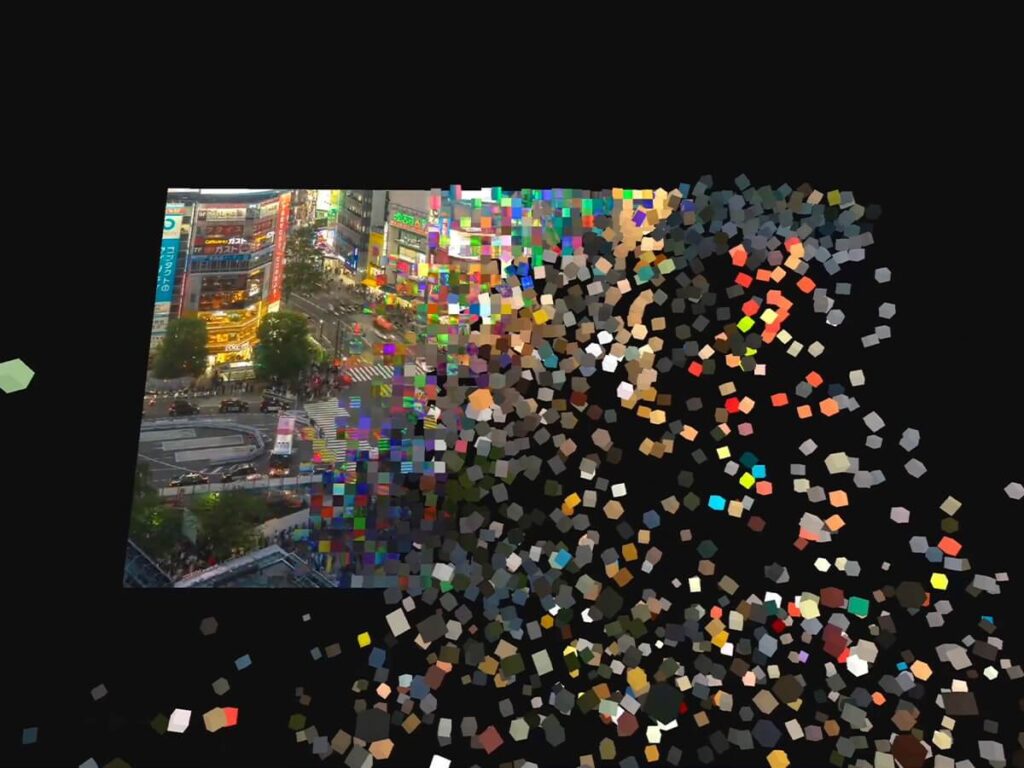

Let’s kick things off by taking a look at the demo.

Whoa, what is this?! Or as we say in Japanese: “Nanja korya!!!”

Concept

Pixels

Pixels are the fundamental units that make up the “form” we see on digital screens. And the overall “shape” is nothing more than a collection of those pixels… I’ve always been fascinated by the concept of pixels, so I’ve been creating pixel art using Three.js and shaders. I love pursuing unique visuals that spark curiosity through unexpected expressions. For example, I’ve previously explored reconstructing live camera streams by replacing individual pixels with various concrete objects to create a playful digital transformation. While making things like that, a thought suddenly struck me:What would happen if I extruded these pixels into 3D space?

Gravity

Another major theme I’ve been exploring in recent years is “Gravity”. Not anti-gravity! Just plain gravity! While building websites powered by physics engines, I’ve been chasing the chaos and harmony that unfold within them. I’ve also long wanted to take the Gravity I’ve been working with in 2D spaces and expand it into 3D.

All of these ideas and explorations form the starting point for this project.Just like with pixel art, I treat a single “InstancedMesh” in Three.js as one “pixel”. I arrange these neatly in a grid so they form a flat plane… then turn each one into a 3D voxel. On top of that, I create a corresponding rigid body for each voxel and place them under a physics engine.

Tech stack used in this demo:

- Rendering: Three.js + Shaders

- Physics: Rapier

- Animation/Control: GSAP

- GUI: Tweakpane

Alright – let’s get started!

Implementation

We’ll implement this in three main steps.

1. Create a Flat Plane from InstancedMeshes and Rigid Bodies

Approach: The goal is to coordinate a collection of InstancedMesh units with their corresponding rigid bodies so that, together, they appear as a single, flat video plane.

Think of it as creating something like this: (For clarity, I’ve added small gaps between each InstancedMesh in the image below.)

Pixel Unit Settings

We decide the size of each pixel by dividing the video texture based on the desired number of columns. From this, we calculate the necessary values to arrange square InstancedMesh properly.

We store all the necessary data in this.gridInfo. This calculation is handled by the calculateGridMetrics function within utils/mathGrid.js.

// index.js

/**

* Computes and registers grid metrics into this.gridInfo:

* - Dimensions (cols, rows, count)

* - Sizing (cellSize, spacing)

* - Layout (width, height)

*/

buildScene() {

//...

this.gridInfo = calculateGridMetrics(

this.videoController.width,

this.videoController.height,

this.app.camera,

this.settings.cameraDistance,

this.params,

this.settings.fitMargin

);

//...

}Creating Rigid Bodies and InstancedMeshes

Using the grid information we obtained earlier, we’ll now create the rigid bodies to place in the physics world, along with the corresponding InstancedMeshes. We’ll start by creating and positioning the rigid bodies first, then create the InstancedMeshes in sync with them.

The key point here is that – anticipating the transition to voxels, we instantiate each unit using BoxGeometry. However, we initially flatten them in the vertex shader by scaling the depth close to zero. This allows us to initialize them so they visually appear as flat tiles, just like ones made with PlaneGeometry.

Each of these individual InstancedMeshes will represent one pixel.

The createGridBodies method is the foundation of everything. As soon as the gridInfo is determined, this method generates all the necessary elements at once: creating the rigid bodies, setting their initial positions and rotations, and generating the noise and random values required for the vertex effects and box shapes.

// core/PhysicsWorld.js (simplified)

createGridBodies(gridInfo, params, settings) {

// Prepare data structures (TypedArrays for performance)

this.cachedUVs = new Float32Array(count * 2);

this.noiseOffsets = new Float32Array(count);

const randomDepths = new Float32Array(count);

for (let i = 0; i < count; i++) {

const x = startX + col * spacing;

const y = startY + row * spacing;

const u = (col + 0.5) / cols;

const v = (row + 0.5) / rows;

// Caching UVs for the cube drop

this.cachedUVs[i * 2] = u;

this.cachedUVs[i * 2 + 1] = v;

// Generate noise and random depth scales

this.noiseOffsets[i] = computeNoiseOffset(i);

randomDepths[i] = params.shape === "random" ? (Math.random() < 0.2 ? 1.0 : 1.0 + Math.random() * 1.5) : 1.0;

// Create RAPIER Rigid Bodies and Colliders

const rbDesc = RAPIER.RigidBodyDesc.fixed().setTranslation(x, y, 0);

const rb = this.world.createRigidBody(rbDesc);

const clDesc = RAPIER.ColliderDesc.cuboid(halfSize, halfSize, halfSize * depthScale);

this.world.createCollider(clDesc, rb);

}

}We initialize each instance as a cube using BoxGeometry.

// view/PixelVoxelMesh.js

createGeometry() {

return new THREE.BoxGeometry(

this.gridInfo.cellSize, this.gridInfo.cellSize, this.gridInfo.cellSize);

}We use setMatrixAt to synchronize the positions and rotations of the InstancedMesh with their corresponding rigid bodies.

// view/PixelVoxelMesh.js

setMatrixAt(index, pos, rot) {

this.dummy.position.set(pos.x, pos.y, pos.z);

this.dummy.quaternion.set(rot.x, rot.y, rot.z, rot.w);

this.dummy.scale.set(1, 1, 1);

this.dummy.updateMatrix();

this.mesh.setMatrixAt(index, this.dummy.matrix);

}Playing the Video on a Single Large Plane

We pass the video as a texture to the material of these InstancedMeshes, turning the collection of small units into one large, cohesive plane. In the vertex shader, we specify the corresponding video coordinates for each InstancedMesh, defining the exact width and height each instance is responsible for. At first glance, it appears as a regular video playing on a flat surface – which is how the visual seen at the beginning is achieved.

// view/PixelVoxelMesh.js

createMaterial(videoTexture) {

return new THREE.ShaderMaterial({

uniforms: {

uMap: {value: videoTexture},

uGridDims: {value: new THREE.Vector2(this.gridInfo.cols, this.gridInfo.rows)},

uCubeSize: {value: new THREE.Vector2(this.gridInfo.cellSize, this.gridInfo.cellSize)},

//...// vertex.glsl

float instanceId = float(gl_InstanceID);

float col = mod(instanceId, uGridDims.x);

float row = floor(instanceId / uGridDims.x);

vec2 uvStep = 1.0 / uGridDims;

vec2 baseUv = vec2(col, row) * uvStep;2. Adding Effects with Shaders

Approach: In the vertex shader, we initially set the depth to a very small value (0.05 in this case) to keep everything flat. By gradually increasing this depth value over time, the original cube shape – created with BoxGeometry – gets restored.

This simple mechanism forms the core of our voxelization process.

One of the key points is how we animate this depth increase. For this demo, we’ll do it through a “ripple effect.” Starting from a specific point, a wave spreads outward, progressively turning the flat InstancedMeshes into full cubes.

On top of that, we’ll mix in some glitch effects and RGB shifts during the ripple, then transition to a pixelated single-color look (where each entire InstancedMesh is filled with the color sampled from the center of its UV). Finally, the shapes settle into proper 3D voxels.

In the demo, I’ve prepared two different modes for this ripple effect. You can switch between them using the “Organic” toggle in the GUI.

Ripple Effect

JavaScript: Calculating the Wave Range

In controllers/SequenceController.js, the targetVal – the final goal of the animation – is calculated based on the distance from the wave’s origin to the farthest InstancedMesh. This ensures the ripple covers every element before finishing.

//controllers/SequenceController.js

startCollapse (u, v) {

//...

pixelVoxelMesh.setUniform("uRippleCenter", { x: u, y: v });

const aspect = this.main.gridInfo.cols / this.main.gridInfo.rows;

const centerX = u * aspect;

const centerY = v;

const corners = [ { x: 0, y: 0 }, { x: aspect, y: 0 }, { x: 0, y: 1 }, { x: aspect, y: 1 } ];

const maxDist = Math.max(...corners.map((c) => Math.hypot(c.x - centerX, c.y - centerY)));

// Calculate final ripple radius based on maximum distance and spread

const targetVal = maxDist + params.effectSpread + 0.1;

gsap.to(pixelVoxelMesh.material.uniforms.uVoxelateProgress, {

value: targetVal,

//...Vertex Shader: Controlling the Transformation Progress

- Global Progress (

uVoxelateProgress): This value increases up totargetVal, ensuring the wave expands until it reaches the furthest corners of the screen. - Local Progress: Each InstancedMesh begins its transformation the moment the wave passes its position. By using functions like

clampandsmoothstep, the progress value is locked at1.0once the wave has passed – this ensures that every mesh eventually completes its transition into a full cube.

We start with a flat 0.05 depth and scale up to the targetDepth during voxelization, applying the progress value from the selected mode to drive the transformation.

// vertex.glsl

// --- Progress ---

float progressOrganic = clamp((uVoxelateProgress - noisyDist) / uEffectSpread, 0.0, 1.0);

float progressSmooth = smoothstep(distFromCenter, distFromCenter + uEffectSpread, uVoxelateProgress);

// --- Coordinate Transformation (Depth) ---

float finalScaleVal = mix(valSmooth, valOrganic, uOrganicMode); // Mix between Smooth and Organic values based on mode uniform

float baseDepth = 0.05;

float targetDepth = mix(1.0, aRandomDepth, uUseRandomDepth);

float currentDepth = baseDepth + (targetDepth - baseDepth) * finalScaleVal;

vec3 transformed = position;

transformed.z *= currentDepth;

Organic Mode On

The wave’s position and propagation are driven by noise. The voxelization transforms with a bouncy, organic elasticity.

// vertex.glsl

// --- A. Organic Mode (Noise, Elastic) ---

// Add noise to the distance to create an irregular wave front

float noisyDist = max(0.0, distFromCenter + (rndPhase - 0.5) * 0.3);

// Calculate local progress based on voxelization progress and spread

float progressOrganic = clamp((uVoxelateProgress - noisyDist) / uEffectSpread, 0.0, 1.0);

// Apply elastic easing to the progress to get the organic shape value

float valOrganic = elasticOut(progressOrganic, 0.2 + rndPhase * 0.2, currentDamp);Organic Mode Off (Smooth Mode)

The wave propagates linearly across the grid in an orderly manner. The voxelization progresses with a clean, sine-based bounce, synchronized perfectly with the expansion.

// vertex.glsl

// --- B. Smooth Mode (Linear, Sine) ---

// Calculate smooth progress using a simple distance threshold

float progressSmooth = smoothstep(distFromCenter, distFromCenter + uEffectSpread, uVoxelateProgress);

// Calculate bounce using a sine wave

float valSmoothBounce = sin(progressSmooth * PI) * step(progressSmooth, 0.99);

// Combine linear progress with sine bounce

float valSmooth = progressSmooth + (valSmoothBounce * uEffectDepth);Within each mode, numerous parameters – RGB shift, wave color, width, and deformation depth – work together in harmony. Feel free to play around with these settings under the “VISUAL” section in the GUI. I think you’ll discover some truly fascinating and fun Pixel-to-Voxel transformations!

3. Let’s get physics, physics. I wanna get physics.

Approach: So far, we’ve focused on the transformation in the InstancedMeshes – from flat tiles to full cubes. Next, we’ll let the pre-created rigid bodies come to life inside the physics engine. The goal is this: the moment the shapes fully turn into cubes, the corresponding rigid bodies “wake up” and start responding to the physics engine’s gravity, causing them to drop and scatter naturally.

Simulating the Ripple Effect in JavaScript

The transformation from flat to full cube happens entirely in the vertex shader, so JavaScript has no efficient way to detect exactly when this transformation occurs for each instance on the GPU. The vertex shader doesn’t tell us which specific InstancedMeshes have completed their cube transformation. However, we need this timing information to know exactly when to “wake up” the corresponding rigid bodies so they can respond to gravity and begin their drop. To know exactly when each individual InstancedMesh has finished becoming a cube, we simulate the same ripple effect logic on the JavaScript side that is running in the vertex shader.

// vertex.glsl

float noisyDist = max(0.0, distFromCenter + (rndPhase - 0.5) * 0.3);

float progressOrganic = clamp((uVoxelateProgress - noisyDist) / uEffectSpread, 0.0, 1.0);

float progressSmooth = smoothstep(distFromCenter, distFromCenter + uEffectSpread, uVoxelateProgress);We simulate the progression mentioned above on the JavaScript side.

// core/PhysicsWorld.js

checkAndActivateDrop(rippleCenter, currentProgress, aspectVecX, organicMode, spread, spacing, count, onDropCallback) {

if (!this.dropFlags) return;

const spreadThreshold = spread * 0.98;

for (let i = 0; i < count; i++) {

if (this.dropFlags[i] === 1) continue;

const u = this.cachedUVs[i * 2];

const v = this.cachedUVs[i * 2 + 1];

const noiseOffset = organicMode ? this.noiseOffsets[i] : 0;

const dx = (u - rippleCenter.x) * aspectVecX;

const dy = v - rippleCenter.y;

const distSq = dx * dx + dy * dy;

const threshold = currentProgress - spreadThreshold - noiseOffset;

// Replicating vertex shader ripple logic for physics synchronization

if (threshold > 0 && threshold * threshold > distSq) {

this.dropFlags[i] = 1;

const force = spacing * 2.0;

this.activateBody(i, force);

onDropCallback(i);

}

}

}Progress – Spread – Noise > Distance

How can a single JavaScript if statement stay perfectly in sync with the shader? The secret lies in the fact that both are looking for the exact same moment: when voxelization completes (the value reaches 1.0). Functions like clamp and smoothstep are merely used to clip the values so they don’t exceed 1.0 for visual depth. Once you strip away these visual “clamps”, the logic in JavaScript and the Shader is identical.

JavaScript

Condition-Organic:

Condition-Smooth:

In “Organic” mode, we use this.noiseOffsets—pre-calculated with the computeNoiseOffset function in utils/common.js– following the same logic used in the vertex shader.

Organic ModeLogic:

When progressOrganic reaches 1.0:

Rearranged:

Smooth ModeLogic:

When progressSmooth reaches 1.0:

Rearranged:

One final tip: The logic that decides which cubes to drop currently loops through every instance. I’ve already optimized it quite a bit, but if the cube count grows much larger, we’ll need more mathematical optimizations—for example, skipping calculations for grid cells outside the current wave propagation area (rectangular bounds).

Let me hear rigid body talk, body talk

Manipulating the rigid bodies can lead to all sorts of fun and diverse behaviors depending on the values you tweak. Since there are so many parameters to play with, I thought it might be overwhelming to show them all at once. For this demo and tutorial, I’ve focused the GUI controls on just “DropDelay” and “Dance” mode.

When dropping, the activateBody method applies a random initial velocity to each rigid body. This method is triggered based on the “DropDelay” timing. For the “Dance” mode, the updateAllPhysicsParams method updates the rigid bodies using the specific parameter values.

// core/PhysicsWorld.js

activateBody(index, initialForceScale = 1.0) {

const rb = this.rigidBodies[index];

if (!rb) return;

rb.setBodyType(RAPIER.RigidBodyType.Dynamic);

rb.setGravityScale(0.01);

rb.setLinearDamping(1.2);

rb.wakeUp();

const force = initialForceScale;

// Apply random initial velocity and rotation

rb.setLinvel({

x: (Math.random() - 0.5) * force, y: (Math.random() - 0.5) * force, z: (Math.random() - 0.5) * force

}, true);

rb.setAngvel({

x: Math.random() - 0.5, y: Math.random() - 0.5, z: Math.random() - 0.5

},true);

}

updateAllPhysicsParams(bodyDamping, bodyRestitution) {

this.rigidBodies.forEach((rb) => {

rb.setLinearDamping(bodyDamping);

rb.setAngularDamping(bodyDamping);

const collider = rb.collider(0);

if (collider) collider.setRestitution(bodyRestitution);

rb.wakeUp();

});

}To join the conversation, you can interact with the rigid bodies using your mouse. These interactions are managed by controllers/InteractionController.js, which communicates with core/PhysicsWorld.js via dedicated methods that let you grab and move bodies with Three.js’s Raycaster.

Restoring after the talk

When the “BACK TO PLANE” button is triggered, startReverse in controllers/SequenceController.js temporarily disables gravity for all rigid bodies. To restore the original grid, I implemented a staggered linear interpolation (Lerp/Slerp) that animates each body back to its initial position and rotation saved during creation. This creates a smooth, orderly transition from a chaotic state back to the flat plane.

// controllers/SequenceController.js

startReverse() {

//...

gsap.to(progressObj, {

value: 1 + staggerStrength,

duration: 1.0,

onUpdate: () => {

const globalT = progressObj.value;

cachedData.forEach((data) => {

// Calculate progress (t) with individual stagger delay

let t = Math.max(0, Math.min(1, globalT - data.delay * staggerStrength));

if (t <= 0 || (t >= 1 && globalT < 1)) return;

// Interpolate position and rotation

const pos = {

x: data.startPos.x + (data.endPos.x - data.startPos.x) * t,

y: data.startPos.y + (data.endPos.y - data.startPos.y) * t,

z: data.startPos.z + (data.endPos.z - data.startPos.z) * t

};

qTmp.copy(data.startRot).slerp(data.endRot, t);

// Update RAPIER RigidBody transformation

data.rb.setTranslation(pos, true);

data.rb.setRotation(qTmp, true);

});

// Sync InstancedMesh

physics.syncMesh(pixelVoxelMesh);

}

//...Implementation Notes

Contact Cache (The Memory of the Talk): You might notice the second drop feels slightly less intense than the first. This is likely due to Rapier’s “Contact Pairs” cache persisting within the bodies. For a perfectly fresh simulation, you could regenerate the rigid bodies during each restoration. I’ve kept it simple here as the visual impact is minor.

Syncing with the Render Cycle: You might also notice that the physics step() is called directly within animate() in index.js, driven by requestAnimationFrame. While a Fixed Timestep with an accumulator is standard for consistency, I intentionally omitted it to synchronize with the monitor’s refresh rate. Rather than settling for “one-size-fits-all” precision, I chose to harness the full refresh potential of the machine to achieve a more natural aesthetic flow and fluidity. As a result, this app is quite CPU-intensive, and performance will vary depending on your machine. If things start feeling heavy, I recommend reducing the “Column” value in the GUI to decrease the overall instance count.

As for potential technical improvements, the current setup will hit bottlenecks if the cube count increases significantly. I feel the current count strikes a good balance – letting us feel the transition from pixel to voxel – but handling tens of thousands of cubes would require a different approach.

Rendering Optimization: Instead of CPU-based matrix calculations, position and rotation data can be stored in DataTextures to handle computations in shaders. This represents a substantial improvement and is a concrete next step for further optimization. Alternatively, utilizing Three.js’s WebGPURenderer (with TSL) is another path for optimization.

Physics Strategy: While we could move physics entirely to the GPU – which excels at massive, simple simulations – it can often limit the logic-based flexibility required for specific interactions. For a project like this, using Rapier on the CPU is the right choice, as it provides the perfect balance between high-performance physics and precise, direct control.

Wrap-Up

Using these as a foundation, try creating your own original Pixel-Voxel-Drop variations! Start simple – swap out the video for a different one, or replace the texture with a still photo, for example.

From there, experiment by changing the geometry or shaders: turn the voxels into icy boxes, use Voronoi patterns to create a shattering glass effect, or make only cubes of a specific color drop… Alternatively, you could even integrate this effect into a website’s hero section – which is exactly what I’m planning to do next. The ideas will spread outward, just like the ripple effect itself!

Final Thoughts

Finally, I’d like to express my gratitude to Codrops for reaching out to me this time. Codrops has always inspired me, so it’s truly an honor to be invited by them. Thank you so much.

A special huge thank-you goes to Manoela. I believe it was her single comment about the ripple effect that shaped the direction of this demo. I’ve even named this effect “Manoela’s Ripple.” Thank you for the wonderful hint and inspiration.

And also, about the video used in this demo: Shibuya Crossing Video from Pexels.com.

Watching the dynamic flow of Shibuya Crossing, it perfectly captures the vibe of how rigid bodies collide and interact within a physics engine. Just as pixels and voxels are the fundamental units of a digital shape, each person and each object exists as an independent entity, colliding and moving in their own way. In this gathering of individuals, there is harmony within chaos, and chaos within harmony – this is the very world we all live in.