NASA / JPL-Caltech / Univ. of Arizona

For decades, scientists have pondered whether there’s lightning on Mars. The phenomenon is already confirmed on gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn and considered very likely in Uranus and Neptune. However, definitive evidence of lightning strikes on Earth’s closest neighbors Venus and Mars has remained elusive.

Now, a team of researchers has finally detected electrical discharges in the Martian atmosphere. They are nothing like the miles-long, wrath-of-the-gods lightning we experience on Earth; instead, they look more like the faint electrostatic discharges that occur when rubbing a sweater on a dry day. These discharges occur when airborne dust grains collide with each other after being lifted by strong Martian winds, a process known as triboelectrification.

NASA / JPL

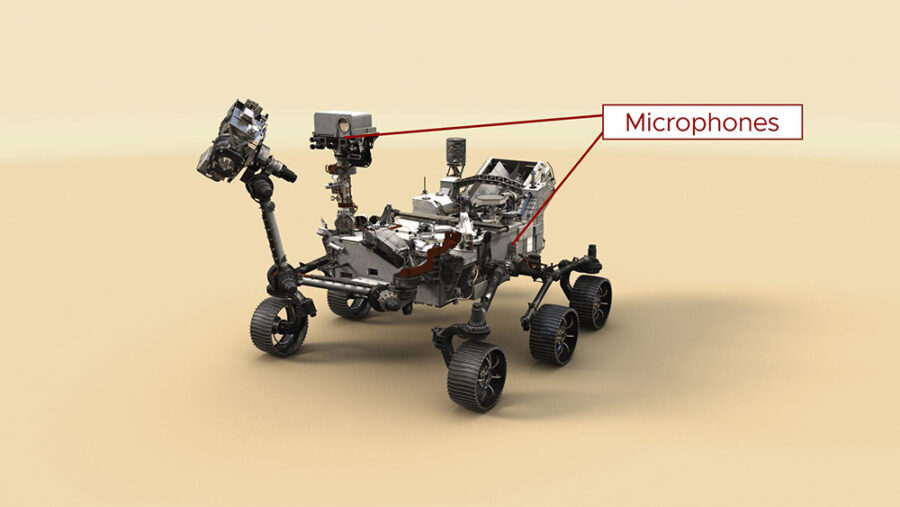

The evidence came from an unlikely instrument: a microphone on NASA’s Perseverance rover, which has been roaming Mars since 2021. The microphone’s primary goal is to characterize winds and atmospheric turbulence, along with diagnosing technical issues on the rover itself. Meanwhile, it collaterally captured the sound from the discharge’s electromagnetic interference, the researchers have found.

The discovery required a degree of luck. On September 27, 2021, a dust devil passed directly above the rover while the microphone was recording. Such flyovers are relatively rare, having occurred only a handful of times since the start of the mission. That the microphone was recording was even luckier, since it only operates for a few minutes every couple of days to save energy and data bandwidth.

“We have plenty of dust devils on Mars, but having the microphone recording at the same time was [pure] chance,” says team member Baptiste Chide (Université de Toulouse, France).

NASA / JPL-Caltech

A few years ago, Chide and other colleagues wrote a paper for Nature analyzing the wind and dust mobilization within the dust devil, and they published the audio recording along with the study. In the recording, they noticed an intriguing clapping sound that they initially attributed to dust grains striking the microphone’s membrane.

But the researchers later realized the mysterious sounds came from miniature shockwaves produced when the dust devil electrically charged suspended dust particles, producing sparks. The connection clicked for Chide while attending a conference on atmospheric electricity a year later. If sparks flew as dust was mobilized, they should generate an audible shockwave. When he reviewed the recordings, he found a second signal that confirmed his suspicions: The discharge produced electromagnetic interference, which arrived a few milliseconds before the shockwave.

The find was equivalent to seeing the lightning before hearing the thunder. “These are two independent signals and that was the confirmation of the discharge,” Chide says.

Mini-flashes of Lightning

By analyzing the delay between the near-instantaneous electromagnetic signal and the slower acoustic shockwave, the researchers calculated the distance of each event from the microphone, enabling them to gauge the discharges’ intensity. They estimated that the most energetic of them released 40 millijoules of energy — comparable to the energy generated by a car’s spark plug.

The team then reviewed all recordings since the start of the mission, covering approximately four years of intermittent operation, finding 55 events in total. Only seven of these had both the acoustic and electric signals; the rest only had the electrical interference.

The low number can be explained by Mars’s terrible acoustics. The low atmospheric pressure and the high concentration of carbon dioxide, which attenuates sound at high and mid frequencies, severely limit how far sound can travel. In that environment, two people standing together “would have to scream to hear each other,” Chide says. That limits the detection range. “We are probing a very small volume around the microphone,” Chide says.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / LANL / CNES /CNRS / INTA-CSIC / Space Science Institute / ISAE-Supaero / Univ. of Arizona

The authors published the new findings November 26th in Nature.

Mars’s rarefied atmosphere explains why these tiny lighting flashes strike. The low pressure, roughly 1% of Earth’s at sea level, and the atmospheric composition result in a low threshold required to ionize gas and produce a discharge in midair. A charge differential of 15 kilovolts per meter is enough to produce a spark on Mars. Producing sparks in the same way on Earth would require around 3 megavolts (3 million volts!) per meter. Triboelectric charging that occurs in terrestrial deserts therefore doesn’t make sparks.

Mars’s thin air also explains the mini-lightning’s short travel distance. The planet’s low atmospheric pressure means that there are very few gas molecules per unit of volume. Since electricity cannot travel in a vacuum, the charge needs to jump from one molecule to the next, ionizing them as it propagates. This chain quickly runs out of molecules to sustain its travel, dying off quickly. The discharges are probably more common at lower altitudes, where the atmospheric pressure is higher.

“The finding is satisfactory, in the sense that it’s something that we knew that must occur, but we had never measured in-situ,” says study coauthor German Martínez (Center for Astrobiology in Madrid, Spain).

Scientists have been looking for this phenomenon for a long time, despite not having a dedicated instrument on the Martian surface. Nevertheless, there were earlier hints. In 2006, Christopher Ruf and Nilton Renno (both University of Michigan) found a strong radio signal coming from the Red Planet, coinciding with a large dust storm. Could that storm have produced triboelectric sparks on steroids? The signal vanished as the storm rotated away from view. “To me, that was clear proof,” Renno says. But later radio observations from the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter failed to detect these signals, and some questioned Renno’s findings.

Christopher Go

The Significance of Sparks

Even if these tiny discharges seem underwhelming to a casual observer, there are compelling reasons to pay close attention to electrical activity on Mars. First, it’s important for exploration, as electric discharges could damage sensitive equipment. Electric fields also play a role in mobilizing dust, and better understanding this process can improve dust storm forecasts, which are important for the safety of spacecraft, rovers, and eventually, astronauts.

A second reason is chemistry. Electrical discharges help form oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide and chlorine-rich salts called perchlorates, extremely reactive substances that disintegrate organic molecules on the surface. Like surface disinfectants, these compounds have potentially been bleaching the Martian surface, wiping clean any signatures of past life on the Red Planet, if it existed.

A third major implication is linked to the long-running controversy over methane. While the Curiosity rover detected the gas at ground level several times, these whiffs never built up enough in the atmosphere for ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) spacecraft to detect them. Some researchers have hypothesized that something is rapidly destroying the methane as it’s released — and electrical discharges could be one such mechanism. “It doesn’t solve the mystery,” Chide says, “but this could be a missing piece of this puzzle.”

Now that the researchers have calculated the energies released by these discharges, they plan to run laboratory experiments to test what kind of chemical reactions they could induce, Chide says.

Until they find out, the evidence suggests an intriguing possibility: If these chemical reactions release chlorine from the perchlorates, do dust devils on Mars leave a chlorine-scented trail behind? Does Mars smells like a swimming pool?