FRIDAY, JUNE 13

■ Bright Arcturus, very high toward the south these evenings, and Spica, below it by about three fists at arm’s length, form an almost perfectly equilateral triangle with dimmer Denebola, Leo’s 2nd-magnitude tail tip, off to their right.

All three sides of the Arcturus-Spica-Denebola triangle are close to 35° long (35.3°, 35.1°, and 32.8°). In 1974 Sky & Telescope‘s George Lovi named this the Spring Triangle to parallel those of summer and winter. For so fine an equilateral, the name ought to stick.

SATURDAY, JUNE 14

■ As we count down the last seven days to official summer (the solstice comes on the night of June 21-22), the Summer Triangle stands high and proud in the east after dark. Its top star is bright Vega. Deneb is the brightest star to Vega’s lower left, by 2 or 3 fists at arm’s length. Look for Altair farther to Vega’s lower right. Altair shines midway in brightness between Vega and Deneb.

If you have a dark enough sky, the Milky Way runs across the bottom of the Summer Triangle from side to side.

SUNDAY, JUNE 15

■ Titan casts its shadow on Saturn tonight! Only every 15 years does Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, cross Saturn’s face from Earth’s viewpoint — and, more visibly, cast its tiny black shadow onto Saturn’ globe. A new series of these events is under way. They will continue every 16 days until October.

Tonight Titan’s tiny shadow crosses Saturn’s disk from 8:21 UT to 14:00 UT June 16th. That’s from 3:21 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. June 16th Central Daylight Time; 1:21 a.m. to 6:00 a.m. June 16th Pacific Daylight Time. Because Saturn is only up in view before and during local dawn no matter where you are, this means western North America is again favored. But Saturn may still be at too low an altitude for the seeing to be steady enough. See Bob King’s Titan Shadow Transit Season Underway.

MONDAY, JUNE 16

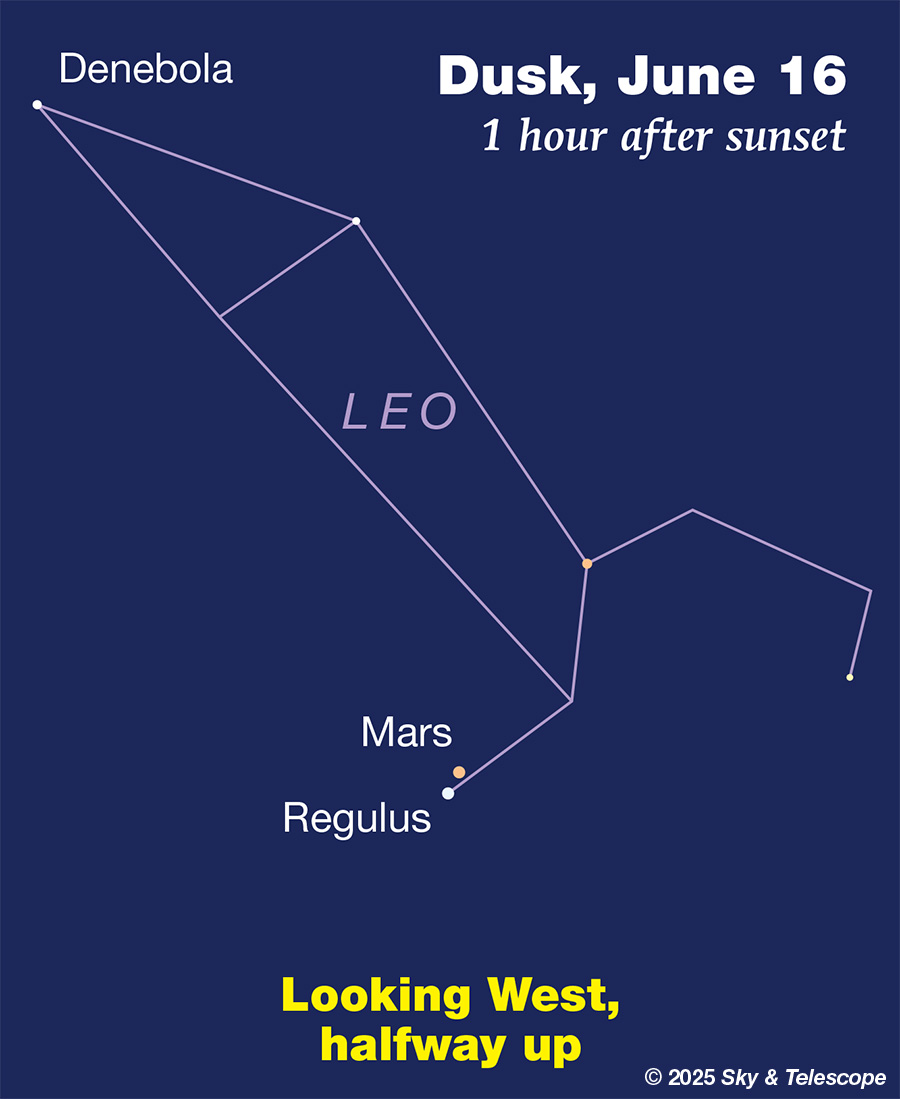

■ Mars and Regulus shine closest together in the west this evening, as shown below. Tonight they’re 0.8° apart (for the Americas), about the width of a pencil held at arm’s length. This is a great time to compare their contrasting colors in binoculars or a telescope at low power.

On paper, Mars is now essentially identical in brightness to Regulus: they’re magnitudes 1.4 and 1.34, respectively. But several factors complicate things, as happens everywhere in nature. Mars’s dark surface markings make one side of the planet a trace darker than the other. Unusual amounts of dust in the Martian atmosphere brighten the globe.

And Mars and Regulus are plainly different in color: pale orange and icy blue-white. Perhaps the brightness-vs.-color response of your observing eye is a little different than was used in the official definition of “visual” magnitude. In particular, our eye lenses yellow as we age. So compared to teenagers, older folks increasingly see everything through yellow filters. Thus blue-trending objects will look slightly dimmer than yellow or orange ones as you get older compared to their true brightnesses as measured by machines.

So how alike in brightness do Mars and Regulus look to you? Take your time. Try to convince yourself that one is slightly brighter, then try to do that with the other. Do so back and forth several times, and see whether one imbalance seems more plausible than the other.

Among variable-star observers, the conventional wisdom is that in an ideal side-by-side comparison like this, most careful people can detect a difference of 0.1 magnitude, and practiced star estimators can do a little better than that.

TUESDAY, JUNE 17

■ Mars and Regulus are again 0.8° apart during evening for the Americas, this time with Mars more directly above the star.

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 18

■ Last-quarter Moon (exact at 3:19 p.m. EDT on this date). Look east just as dawn begins tomorrow morning the 19th, about two hours before sunrise, for Saturn glowing 4° or 5° to the Moon’s right (for North America). By then the Moon will be about half a day past last quarter and its terminator will be starting to look a bit concave. The terminator always appears to move fastest across the Moon’s apparent face at first and last quarter.

Upper left of the Moon and Saturn will be the Great Square of Pegasus, a very early harbinger of fall for early risers even before summer begins.

THURSDAY, JUNE 19

■ Comparing Hercules globular clusters. M13 in the edge of the Keystone of Hercules is famous as one of the best and brightest globular star clusters in the sky. It’s now high in the east after dark. But part of its fame is due to its easily findable location. Less known is its near-twin of a “great cluster in Hercules,” M92 in sparser wilderness 9½° to the northeast, as shown below. M92 is only slightly smaller that M13 and has a look of its own.

“To really appreciate the personalities of these two Hercules clusters, try rapidly going back and forth between them,” writes Matt Wedel in his Binocular Highlight column in the June Sky & Telescope. “Most of the visible differences are down to physical size, with M13 being almost twice as massive as M92. Regardless, each is worthy of the title ‘showpiece object.’ ”

Celestial east is roughly down and celestial north is roughly to the left; this is the scene as you see it when looking high into the eastern sky on late-spring evenings.

Starry Night Pro

FRIDAY, JUNE 20

■ It’s the longest day and the shortest night of the year for the Northern Hemisphere. Summer begins at the solstice, 10:42 p.m. EDT on this date; 7:42 p.m. PDT; 2:42 June 21st Universal Time.

This is also when (in the north temperate latitudes) the midday Sun passes the closest it ever can to being straight overhead, and thus when your shadow becomes the shortest it can ever be where you live. This happens at your local apparent [i.e. solar] noon, which is probably rather far removed from noon in your civil (clock) time.

And if you have a good west-northwest horizon (in mid-northern latitudes), mark carefully where the Sun sets as seen from a particular spot. In a few days you should be able to detect that the Sun is again starting to set a just little south (left) of that point, as it begins its six-month journey to the winter solstice.

■ Tonight and in the coming weeks, watch Mars and Regulus draw farther apart as they sink in the west during and after late twilight. Tonight they’re 2° apart as shown below. In a week they’ll be 6° apart and somewhat lower.

SATURDAY, JUNE 21

■ Look east-northeast at least an hour before Sunday’s sunrise for the waning crescent Moon passing Venus, as shown below. This is a rather distant Moon-Venus passage; they’ll never be less than 6° apart.

SUNDAY, JUNE 22

■ After dark, look southeast for orange Antares, “the Betelgeuse of summer.” (Both are 1st-magnitude “red” supergiants). Around and upper right of Antares are the other, whiter stars of upper Scorpius, forming their familiar, distinctive pattern. The rest of the Scorpion runs down from Antares, then left. The farther north you are, the lower Scorpius will appear.

Also right after dark, spot Arcturus way up high toward the southwest. Three fists below it is Spica. A fist and a half to Spica’s lower right, four-star Corvus, the Crow, is sliding down and away.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury peeks out low in afterglow of sunset, but this will remain a poor Mercury apparition. About 45 minutes after sundown, look for it a little above your west-northwest horizon. Mercury gets just a bit higher in the course of the week, while fading from magnitude –0.7 on June 13th to –0.3 on the 20th.

Venus, brilliant at magnitude –4.3, rises in the east-northeast shortly before the beginning of dawn. Once Venus is up in the clear you can’t miss it. . . until the sky grows too bright. How long can you follow Venus until it’s lost in the growing light of day?

In a telescope, Venus’s shrinking globe (now about 20 arcseconds pole to pole) appears just past half lit, very slightly gibbous.

Mars accompanies Regulus in the western sky after dark. They’re still 2.1° apart on Friday June 13th (for the Americas). They close to just 0.8° apart on the 16th and 17th, then they widen back to 2.1° by Friday the 20th as Regulus moves down to Mars’s lower right.

In a telescope Mars is just a tiny blob 5 arcseconds in diameter. But that’s definitely more extended than pointlike Regulus at anything more than the lowest power.

Jupiter is lost in the glare of the Sun.

Saturn (magnitude +1.1, at the border of Aquarius and Pisces) rises around 1 a.m. In early dawn, find it about four fists at arm’s length upper right of Venus.

The best time to try a telescope on Saturn is just as dawn is beginning, when Saturn has had time to get fairly high out of bad seeing but still stands out against a reasonably dark sky. You may be surprised by Saturn’s appearance; we see its rings nearly edge on this year.

Uranus is out of sight low in the dawn.

Neptune, a telescopic “star” at magnitude 7.9, lurks in Saturn’s background about 1° from it. Try to catch the outermost major planet before dawn begins by using the finder chart for Neptune with respect to Saturn in the June Sky & Telescope, page 51. Using a pencil, put a dot on the path of each planet for your date. Get everything all ready the evening before, so that dawn doesn’t overtake you.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time minus 4 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

For the attitude every amateur astronomer needs, read Jennifer Willis’s Modest Expectations Give Rise to Delight.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas, in either the original or Jumbo Edition. Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, and 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as many more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used.

The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (with 201,000+ stars to magnitude 9.5 and 14,000 deep-sky objects selected to be detectable by eye in large amateur telescopes), and Uranometria 2000.0 (332,000 stars to mag 9.75, and 10,300 deep-sky objects). And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the new Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Do learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

— John Adams, 1770